Does independent directors’monitoring affect reputation?Evidence from the stock and labor markets☆

Jun Du ,Qinghun Hou ,Xuesong Tng ,Yiwei Yo

a School of Accounting and Finance,The Hong Kong Polytechnic University,Hong Kong

b School of Accountancy,Shanghai University of Finance&Economics,China

c School of Accounting,Southwestern University of Finance and Economics,China

d Department of Accountancy,Hang Seng Management College,Hong Kong

1.Introduction

The reputation-related consequences of independent directors are an issue of considerable public and academic interest.Independent directors are widely believed to play an important role in corporate governance.Fama and Jensen(1983)suggest that independent directors can make distinct contributions in aligning managers with the interests of stockholders.The most significant incentive for independent directors to pursue effective board monitoring is to develop their reputations as decision experts.Although Fama and Jensen(1983)indicate that independent directors’reputations hold positive value,it is difficult to empirically evaluate such reputations,as firms rarely disclose the activities of individual directors in the boardroom.Therefore,many studies have inferred the value of independent directors’reputations by investigating the stock or director labor market responses in the wake of extraordinary events.For example,firms with insider-dominated boards are more likely to confront financial distress(Gilson,1990;Harford,2003),report earnings restatements(Srinivasan,2005),face class-action lawsuits(Fich and Shivdasani,2007)and announce director turnovers(Fahlenbrach et al.,2010;Agrawal and Chen,2011).Most of these studies have found that on average investors react negatively to these adverse signals of weak board monitoring and that independent directors suffer reputational penalties if they do not vigilantly monitor top management.Although this line of research provides insights in to the ex post settling-up mechanism of directors’labor market,it is limited in its efforts to impute these corporate failures to poor board monitoring by independent directors(Richardson,2005).More importantly,in the vast majority of firms that do not face these crises,direct evidence of how independent directors help to oversee boards remains scant.

We exploit a unique dataset of independent directors’monitoring efforts to uncover the corresponding effect on independent directors’reputations and career prospects.China’s market regulator,the China Securities Regulatory Commission(CSRC),requires independent directors to publicly disclose their opinions on important managerial decisions.Such directors are expected to say ‘‘no” in board meetings if they believe that a board proposal is not in the interests of shareholders.Furthermore,an independent director’s opinion not only serves as a signal to the external market regarding his/her monitoring efforts,but also may give directors legal relief from potential lawsuits.Thus,the unique disclosure of independent directors’monitoring activities in the Chinese market sheds light on the ‘‘black box”of board function.

We use this context to investigate the consequences of the board disputes that arise when independent directors say ‘‘no.” First,we study whether Chinese investors value independent directors’monitoring efforts.We expect the market to interpret independent directors standing up to firm insiders about any detected irregularities as negative news,as modified opinions disclose board disputes that may be unobservable otherwise.Our focus is the analysis of the stock market reaction to independent directors’opinions regarding director-interlocked firms.Under the reputation hypothesis,the market should respond positively to firms interlocked with directors who say ‘‘no,” given that the announcement of a modified director opinion signals effective monitoring by the opinion-issuing directors.In contrast,the endogenous hypothesis predicts a negative market response to director-interlocked firms,as firms that share the same independent directors may reveal problems that are similar to those of the opinion-receiving firms.Second,to examine the wealth effects of individual independent directors,we analyze the changes in board seats for opinion-receiving firms and other director-interlocked firms.If independent directors develop a reputation for independent monitoring by saying ‘‘no” to controlling shareholders or top executives,then according to Fama and Jensen(1983)they are more likely to keep their board seats in director-interlocked firms or gain more board seats after they issue negative comments on corporate decisions.

We find that firms receiving modified director opinions sustain negative cumulative abnormal returns(CARs),whereas interlocked firms exhibit positive returns around the announcements of modified independent director opinions.There is also a significant turnover for independent directors who say ‘‘no” in opinion-receiving firms subsequent to the issuance of modified independent directors’opinions.Contrarily,the evidence shows that these directors tend to lose more directorships.Our findings are to some extent consistent with the director reputation hypothesis,which suggests that Chinese investors value effective monitoring conducted by independent directors.In the long run,however,vigilant directors are not rewarded for their reputation of effective monitoring,as Fama and Jensen(1983)suggest.One possible explanation is that Chinese firms may self-select lax monitoring for easy managerial control and manipulation.

Our study is closely related to Jiang et al.(2016),who examine the association between independent directors’propensity to issue modified opinions and their career concerns and media coverage.Our study differs from Jiang et al.(2016)in two important ways.First,our results shed light on the dilemma that although investors value effective board oversight,independent directors’monitoring efforts are not rewarded by the director labor market in China,where controlling shareholders often determine who can sit on the board.Second,our findings help differentiate the alternative hypotheses proposed by Fich and Shivdasani(2007)by showing that the market may react differently in opinion-receiving firms and director-interlocked firms when an independent director says ‘‘no.”

We contribute to the literature in several ways.First,we help disentangle the three hypotheses proposed by Fich and Shivdasani(2007).In contrast to most previous studies of director reputation,we evaluate Chinese independent directors’reputations by focusing on their modified opinions of corporate decisions,a positive signal of effective monitoring.Using this novel data,we abstract the legal liability hypothesis and conduct a cleaner test to differentiate between director reputation and the endogenous hypotheses.

Second,we clarify the role of independent directors’reputations in emerging markets.In a related study,Tang et al.(2013)find that independent directors’opinions help to mitigate the agency costs of listed Chinese firms.Our analysis complements this finding by showing that although the stock market values effective board oversight,vigilant directors do not receive rewards from the director labor market in China,by which controlling shareholders can determine who is invited to the board.

Third,our findings in the Chinese context may have implications for regulators who intend to improve the transparency and effectiveness of board governance.As the majority of firms in emerging markets are dominated by controlling shareholders,which may determine the slate of directors,the director labor market therein may drive out independent directors who dare to stand up to firm insiders in board meetings.Without concurrent improvement in market institutions and governance structures,such as in the procedure for nominating and selecting directors,the expected effect of disclosing independent directors’opinions can hardly be sustained in the long run.

This paper continues as follows.Section 2 introduces the institutional background and develops the hypotheses.Section 3 describes the sample and variables.Sections 4 and 5 provide the results.Section 6 presents the robustness checks.Section 7 concludes the paper.

2.Institutional background and hypothesis development

2.1.Institutional background

In response to the great expectations for the improvement of corporate governance and the mitigation of tunneling among controlling shareholders,the independent director system was introduced in China in the 1990s.In the Guidelines for the articles of association of listed companies(CSRC,1997),the CSRC suggests for the first time that listed firms appoint independent directors at their discretion.Following this suggestion,quite a few Chinese firms began to establish board positions for independent directors,particularly firms seeking to list in overseas markets.However,a wave of financial scandals in the late 1990s in firms that had appointed independent directors triggered public outcry about the effectiveness of independent monitoring in China.1For example,a listed department store,Zhengzhou Baiwen(stock ID:600898),which had appointed independent directors as early as 1995,was found guilty of numerous financial scandals in 2001.Mr.Jiahao Lu,the former independent director of Zhengzhou Baiwen,received public censure from the CSRC and was fined RMB100,000 for his negligence in overseeing the fraudulent firm.The independent director system was criticized as being a ‘‘flower vase” in the boardroom,merely decorative and of little use in improving corporate governance.

To rebuild market confidence in independent board monitoring,the CSRC published the Guiding opinion on establishing an independent director system in listed companies in 2001,mandating greater transparency in the monitoring of board and managerial decisions(CSRC,2001).According to the 2001 opinion,by mid-2003,all listed Chinese firms were expected to have set up an independent director system,under which a minimum of one third of the board directors would be independent directors.Notably,the Chinese regulator imposes an additional disclosure requirement that differs from the board regulations in other major capital markets.Listed Chinese firms should disclose any events or transactions that independent directors believe may affect the interests of minority shareholders,such as the nomination,appointment and dismissal of directors and senior executives;the remuneration of directors and senior executives;material inter-corporate loans to shareholders and other affiliated entities;and other issues stipulated in company charter provisions.In addition,the2001 CSRC opinion classifies independent directors’opinions into two major categories:the standard clean opinion and the modified director opinion,comprising qualified and adverse opinions and disclaimers of opinion.If independent directors disagree on a particular corporate issue,then the firm should disclose their views separately.

Following the2001 CSRC opinion,the independent directors of listed Chinese firms began to publicly comment on issues that were important to the firms they served.In the first couple of years,no independent directors issued negative opinions on corporate decisions.It was not until 2004 that modified independent director opinions emerged,when the CSRC gave independent directors the additional power to oversee controlling shareholders and senior executives.For example,according to a CSRC circular(CSRC,2005),independent directors have the right to employ an independent accounting firm to inspect any doubtful corporate decisions,if all of the firm’s independent directors believe an audit is necessary.

2.2.Literature review

Independent directors’monitoring of managers is widely considered one of the most important functions of corporate boards in protecting shareholder interests.Fama and Jensen(1983)propose that the most direct incentive for independent directors to make independent judgments on managerial decisions is to establish their reputations as monitoring experts.They predict that independent directors who effectively oversee their serving boards may be rewarded with additional board seats.

An extensive literature examines the consequences of effective monitoring and the characteristics of independent directors.For example,more independent directors on a board is associated with stronger CEO turnover and performance sensitivity(Weisbach,1988;Conyon and He,2011),decreased negative market reaction to announcements of tender offers for bidding firms(Byrd and Hickman,1992)and increased positive market reaction to announcements of poison pills(Brickley et al.,1994).Several recent studies have documented mixed evidence on the monitoring role of independent directors.Duchin et al.(2010)and Faleye et al.(2011)point out that too strong a presence of independent monitoring may undermine corporate performance.Fahlenbrach et al.(2010)provide evidence that independent directors with executive expertise do not affect the appointing firm’s operating performance,decision making or managerial compensation.Almost all of the studies in this camp have evaluated the effectiveness of independent monitoring based on the documented associations.Few studies have directly examined the independent monitoring efforts of independent directors,as firms rarely disclose disputes that occur inside of the boardroom.

Another growing body of literature infers the value of independent directors by investigating observable corporate events.Srinivasan(2005)finds that independent directors,particularly those serving on audit committees,are more likely to leave the firms that restate their earnings and subsequently lose their board seats at other firms.Fich and Shivdasani(2007)examine the market reaction to the announcement of lawsuits and director turnover in firms interlocked with fraud-tainted independent directors.They find a negative abnormal stock return associated with fraud announcements in director-interlocked firms.Moreover,independent directors generally retain their board seats in sued firms,but lose significant directorships in interlocking firms.Both studies explain the decline of directorships for fraud-affiliated independent directors as reputational penalties.However,independent directors may be innocent in the context of financial fraud,as they may uncover the fraud and hence should not be held accountable(Richardson,2005),or they may be unaware of the fraud due to limited information from management(Fich and Shivdasani,2007).More importantly,although the evidence reported in these two studies is consistent with the reputation hypothesis,Fich and Shivdasani(2007)also point out that it is difficult to exclude two other distinct,but not mutually exclusive,explanations for the negative market reaction and decline in directorships.The endogenous hypothesis predicts that firms with similar board structures and operating environments tend to appoint independent directors with similar attributes.A lawsuit announcement signals that director-interlocked firms are susceptible to similar financial fraud and independent directors may voluntarily reduce their other directorships to focus their monitoring efforts on the sued firms.The other is the litigation hypothesis,under which the market is concerned that fraud-tainted independent directors may not be able to devote enough time and effort to monitoring director-interlocked firms.As a result,independent directors choose to hold fewer board seats to reduce the potential litigation risk.

2.3.Hypothesis development

The director opinion data from the Chinese stock market provide a good opportunity to conduct cleaner tests on the monitoring and reputational roles of independent directors.Following Tang et al.(2013),we measure independent board monitoring as the issuance of modified director opinions.Of the three hypotheses proposed by Fich and Shivdasani(2007),the litigation hypothesis is of less concern in our study.According to Article 113 of China’s Company Law,directors who participate in adopting a board resolution are held liable for any violation of law or regulation resulting from the resolution.‘‘However,if a director is proven to have expressed his objection to the vote on such resolution and his objection was recorded in the minutes,then the director may be exempted from liability” (Standing Committee of National People’s Congress,2005).Anecdotal evidence also suggests that an independent director may be exempted from the CSRC’s enforcement action if he/she has said ‘‘no” to a board resolution that violates law or market regulation and causes losses to the firm.2In the notorious financial fraud case of Xinjiang Tunhe(stock ID:600073),the firm’s two independent directors,Mr.Houwen Du and Mr.Jie Wei,resigned from their board seats in June2004.The board directors and top executives were later punished by the CSRCfor the firm’s false statement in its 2003 annual report,with the exception of Mr.Du,who was proven to have said ‘‘no” in previous board meetings in April 2004(Li,2004).As litigation risk is low for independent directors who say ‘‘no” in board meetings,we only consider the testable implications of the other two competing hypotheses(reputation and endogenous)concerning the role of independent directors,as presented by Fich and Shivdasani(2007).

To distinguish between the reputation and endogenous hypotheses,we first examine the market reaction associated with directors’opinion announcements in director-interlocked firms.If Chinese investors value independent directors’active monitoring efforts,then the reputation hypothesis predicts that the market will react positively to the issuance of modified director opinions for firms interlocked with the independent directors who say ‘‘no” in board meetings.Under the endogenous monitoring hypothesis,firms with similar firm and governance characteristics tend to select independent directors with similar attributes.If a modified director opinion serves as a signal of board disputes to the market,investors may suspect that the director interlocked firm has problems similar to those of the opinion receivers.Therefore,the endogenous hypothesis predicts a negative market reaction associated with the announcement of modified director opinions in director-interlocked firms.

Second,we investigate the changes in independent directors’board seats in interlocking firms.Fama and Jensen(1983)point out that the most direct incentive for independent directors is to establish good labor market reputations.Those who perform effective board monitoring are likely to be rewarded with additional board seats,whereas those who perform poorly will suffer board seat losses.Srinivasan(2005)and Fich and Shivdasani(2007)find evidence consistent with the prediction of reputational loss for fraud-tainted independent directors.We believe an independent director can establish a good reputation for independent monitoring by issuing a modified director opinion.Thus,we predict that the possibility of losing directorships at other firms is negatively associated with independent directors’issuance of modified opinions.In contrast,the endogenous hypothesisargues that independent directors may voluntarily cut their board seats to reduce their workloads or to protect their reputations when they anticipate or detect adverse events(Yermack,2004;Fich and Shivdasani,2007;Fahlenbrach et al.,2010).In this context,we predict a decline in independent directorships following announcements of modified director opinions.

We also examine whether independent directors can retain their board seats in the firms they serve if they say ‘‘no” in board meetings.Shivdasani and Yermack(1999)argue that CEOs may prefer lax monitoring and thus consider poor monitors as attractive candidates for their boards.Alternatively,directors may voluntarily leave poorly performing firms at a high rate to reduce the damage to their reputations,limit legal liability or avoid the higher workload that boards usually undertake when performance decreases(Vafeas,1999).Based on these two arguments,we predict that independent directors are more likely to lose board seats in the firms they serve if they issue modified director opinions.

3.Data and sample description

3.1.Data sources

The data for this study come from the China Stock Market Accounting Research(CSMAR)database.The initial sample covers all 23,805 independent director opinions announced between January 2005 and December 2010,inclusive.First,we exclude the following observations:(a)opinions not coded by the database(CSMAR item c05002b=.);(b)opinions coded as ‘‘other type” (CSMAR item c05002b=7),as they cannot be directly classified as either clean or modified;(c)opinions on Chinese companies’‘‘share trading reform”(CSMAR item c04002b=12),as this is not a normal operating business decision;and(d)repetitive observations.We obtain 18,634 independent director opinions after the first screening procedure.Second,we manually identify 70 additional modified independent director opinions from the original independent director announcements classified by the CSMAR database either as missing(adding 55 cases)or obscurely as ‘‘other type”(adding 15 cases).Third,we require each observation to have the necessary CSMAR data on market capitalization,the independent directors’bio data,financial statements,corporate governance variables and necessary daily price data to compute CARs.To be consistent with the literature,we also exclude firms operating in the finance industry.Overall,10,142 independent director opinions meet the selection criteria,of which 138 are modified director opinions.The sample includes 1429 distinct firms receiving independent director opinions and 1298 distinct director-interlocked firms.

3.2.Sample description

Table 1 presents the sample’s descriptive statistics.Panel A shows the yearly distribution of independent director opinions and the firms that receive them.From 2005 to 2010,138 modified director opinions were issued,accounting for 1.36%of the total director opinions.The number of modified director opinions range from a low of 2 in 2008 and 2009 to a high of 67 in 2006.During the sample period,on average,2.66%firms received modified independent director opinions.

Panel B of Table 1 presents the breakdown of modified independent director opinions by corporate issues.We group the 11 types of business decisions coded by the CSMAR database into three major types:(1)opinions on personnel and compensation issues,(2)opinions on financial reporting and auditing issues and(3)opinions on major operating issues other than personnel,compensation,financial reporting and auditing issues,such as related-party transactions,guaranteed loans and mergers and acquisitions.Note that an independent director’s opinion may involve multiple corporate events.The most frequent single event discussed in modified director opinions is guaranteed loans.Financial reports,related-party transactions and personnel issues are other events frequently discussed by independent directors.Of the 145 events disclosed in the modified director opinions,18 involved personnel and compensation issues,28 involved financial reporting and auditing issues and 99 involved other major operating decisions.

We also examine the degree of severity of independent director opinions in Panel C of Table1.The majority of director opinions are standard and account for 98.62%of the total opinions.Abstention,adverse and disagreement opinions are the top three modified opinions in the sample period,accounting for 0.45%,0.35%and 0.27%of the total number of director opinions,respectively.

4.Market reactions to modified independent director opinions

In this section,we examine whether Chinese investors value independent director opinions after controlling for opinion characteristics,corporate governance factors,financial statement variables and a set of director characteristics.

4.1.Variable descriptions

We use CAR_EVNTFIRM to measure the3-day CARs around the dates of independent director opinions in opinion-receiving firms.The market model is used to measure the daily abnormal returns:where Rmtis proxied by the CSMAR value-weighted return.The model is estimated over a period of 256 to 7 days before the opinion announcement date,requiring a minimum estimation period of 120 days.Market reaction is defined asAlternatively,we use CAR_LOCKEDFIRM to measure the market reaction in director-interlocked firms to modified independent director opinions.

Table 1 Sample of independent director opinions.

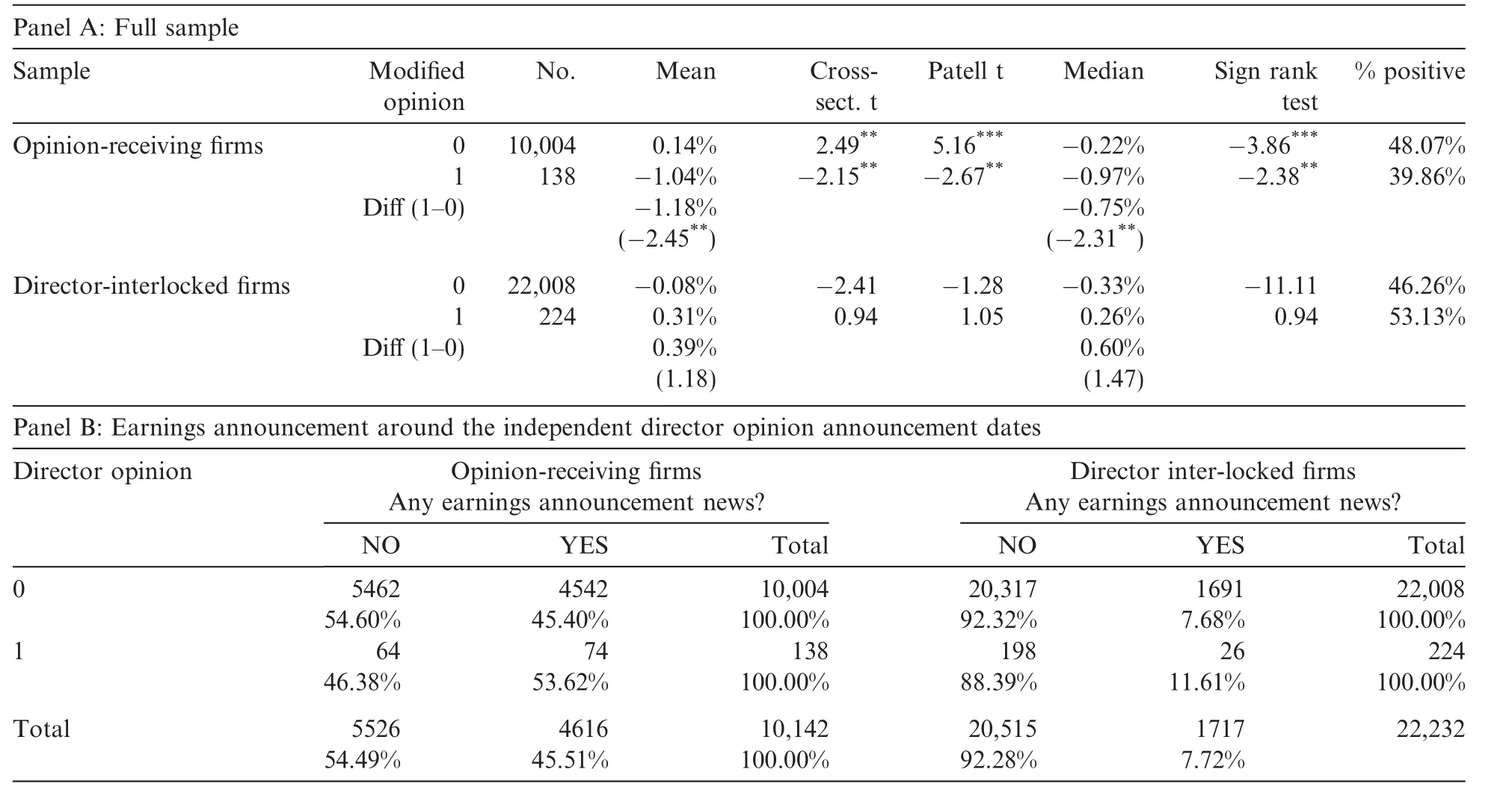

In Panel A of Table 2,we report the results for the full sample.Consistent with Tang et al.(2013),we find that the market reacts negatively when firms announce receiving modified director opinions.The 3-day CARs are systematically negative and significantly different from zero.The mean(median)of the CAR is-1.04%(-0.97%),suggesting that the firms suffer additional value decline due to the information released in modified director opinions.Both the t-statistics for the mean differences and the z-statistics from the Wilcoxon tests indicate that firms receiving modified director opinions exhibit significantly negative stock returns compared with firms reporting clean director opinions.

Panel A also presents the market reaction results for director-interlocked firms.As predicted by the reputation hypothesis,the firms that are interlocked with independent directors who issue modified reports expe-rience positive market reactions.The mean and median of the 3-day CARs for interlocking firms are 0.31%and 0.26%,respectively,and the mean and median CARs for firms that are interlocked with independent directors who issue clean opinions are significantly negative.Panel A also shows that although the average CARs are positive,46.87%of firms that are interlocked with directors who issue modified opinions experience negative stock returns.

Table 2 Univariate analysis of the cumulative abnormal returns around directors’opinion announcement dates.

We then condition the CAR analysis on possible confounding earnings announcement effects.We define a concurrent earnings announcement event if it is announced within the same(-1,+1)window as an independent director’s opinion announcement.Panel B of Table2 shows that 45.51%of directors’opinions are accompanied by a quarterly,interim or annual earnings announcement.Only 7.72%of director-interlocked firms publish their own earnings within the 3-day period surrounding interlocking directors’opinion announcements.In the following section,we test whether these confounding earnings announcements affect the market reaction to independent director opinions.

We perform the empirical analysis by partitioning the full sample into opinion-receiving and director interlocked firms.Specifically,we use the indicator variable MDO_EVNTFIRM to differentiate between firms that receive modified independent director opinions and those that receive clean independent director opinions.Similarly,in the subsample of interlocking firms,we use MDO_LOCKEDFIRM to identify firms that are interlocked with directors who issue modified independent director opinions.

We control for the following variables in the analyses of market returns.First,following Bai et al.(2004),Larcker et al.(2007)and Dey(2008),who document agency conflicts between controlling shareholders and minority shareholders,we examine four individual governance variables to construct a governance index and to capture the agency costs of controlling shareholders:(1)BLOCK,set to 1 if the percentage of ownership held by the largest shareholder is higher than the median and 0 otherwise;(2)CONTROL DISPERSION,set to 1 if the control rights is greater than the cash flow rights and 0 otherwise;(3)LESSINSTIHLD,set to 1 if the percentage of ownership held by institutional investors is less than the median and 0 otherwise;and(4)DUALITY,set to 1 if the firm’s chairman also holds the CEO position and 0 otherwise.The CGINDEX is the sum of these four indicator variables,ranging from 0 to 4.A higher CGINDEX suggests more severe entrenchment among controlling shareholders.

A set of control variables related to the determinants of issuing independent director opinions identified by Tang et al.(2013)are also included in the regression of market reactions.As the market reacts differently to independent director opinions on different corporate decisions(Tang et al.,2013),we use three indicator variables to identity whether the event is related to personnel,financial or operating decisions(ISSUE_PERSONNEL,ISSUE_FINANCIAL or ISSUE_OPERATING,respectively).We use firm size(FIRMSIZE)and market-to-book ratio(M/B)to capture the expected stock return(Fama and French,1992)and return on assets(ROA)to control sample firms’operating performance.To control financial risk,we include indicator variables,namely ST to identify the firms that are accorded by the CSRC as receiving ‘‘special treatment”(Jiang and Wang,2008)and MAO to identify firms that receive modified audit opinions.The percentage of board members who are independent directors(%INDBOARD)and have chairman and CEO duality(DUALITY)are also included following Fama and Jensen(1983),Brickley et al.(1994)and Hermalin and Weisbach(2003).As institutional investors can alleviate agency costs(Bushee,1998;Chung et al.,2002;Cornett et al.,2007;Yuan et al.,2008;Yao et al.,2010),we include institutional shareholdings(INSTIHLD).Wealso consider firm-level director information in the regression analysis,such as the presence of female independent directors on the board(IFFEMALE)and the average age,tenure,director compensation and board seats of independent directors(MAGE,MTENURE,MPAY and MDIRECTORSHIPS,respectively).We control for factors such as whether any opinion-issuing independent directorssit in the compensation or audit committees(IFCOMPCOMM and IFAUDCOMM,respectively)or have financial or executive expertise(IFFINEXPT and IFEXEEXPT,respectively;e.g.,DeFond et al.,2005;Larcker et al.,2007;Adams and Ferreira,2009;Gul et al.,2011;Srinidhi et al.,2011;Lin et al.,2012).In the subsample of director interlocked firms,we add additional variables to the regression of market reactions.Following Fich and Shivdasani(2007),we control for whether interlocked firms are in the same industry(SAMEINDUSTYR)and whether an opinion-receiving firm receives a modified audit opinion(MAO_EVNTFIRM).

To control for the confounding effects of concurrent earnings announcements,we also construct two variables,EARNNEWS and EARNSUR,to measure whether there is an earnings release near the director’s opinion announcement and the magnitude of the earnings surprise.We summarize each of our variable definitions in Appendix A.

4.2.Market reaction for opinion-receiving firms

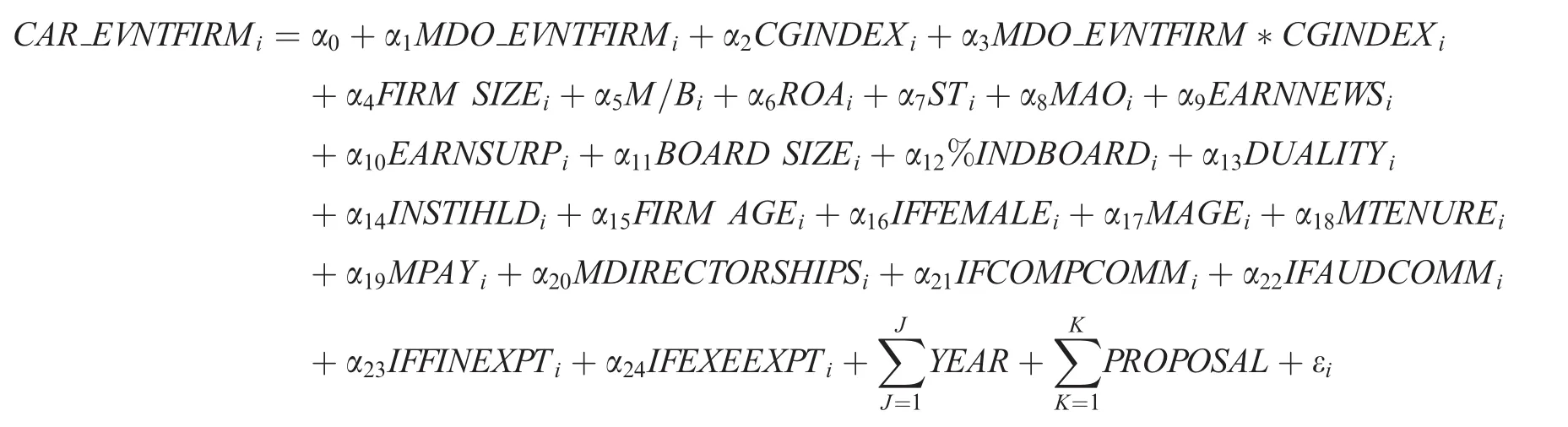

To ensure that the market reaction to the independent director opinions documented in Table 2 is not biased due to correlated omitted variables,we estimate the following pooled cross-sectional regression using the opinion-receiving sample as follows

where all of the variables are defined in Appendix A.Following Jiang et al.(2016),we include proposal-fixed effects to control for the endogeneity that may arise from possibly omitted explanatory variables.

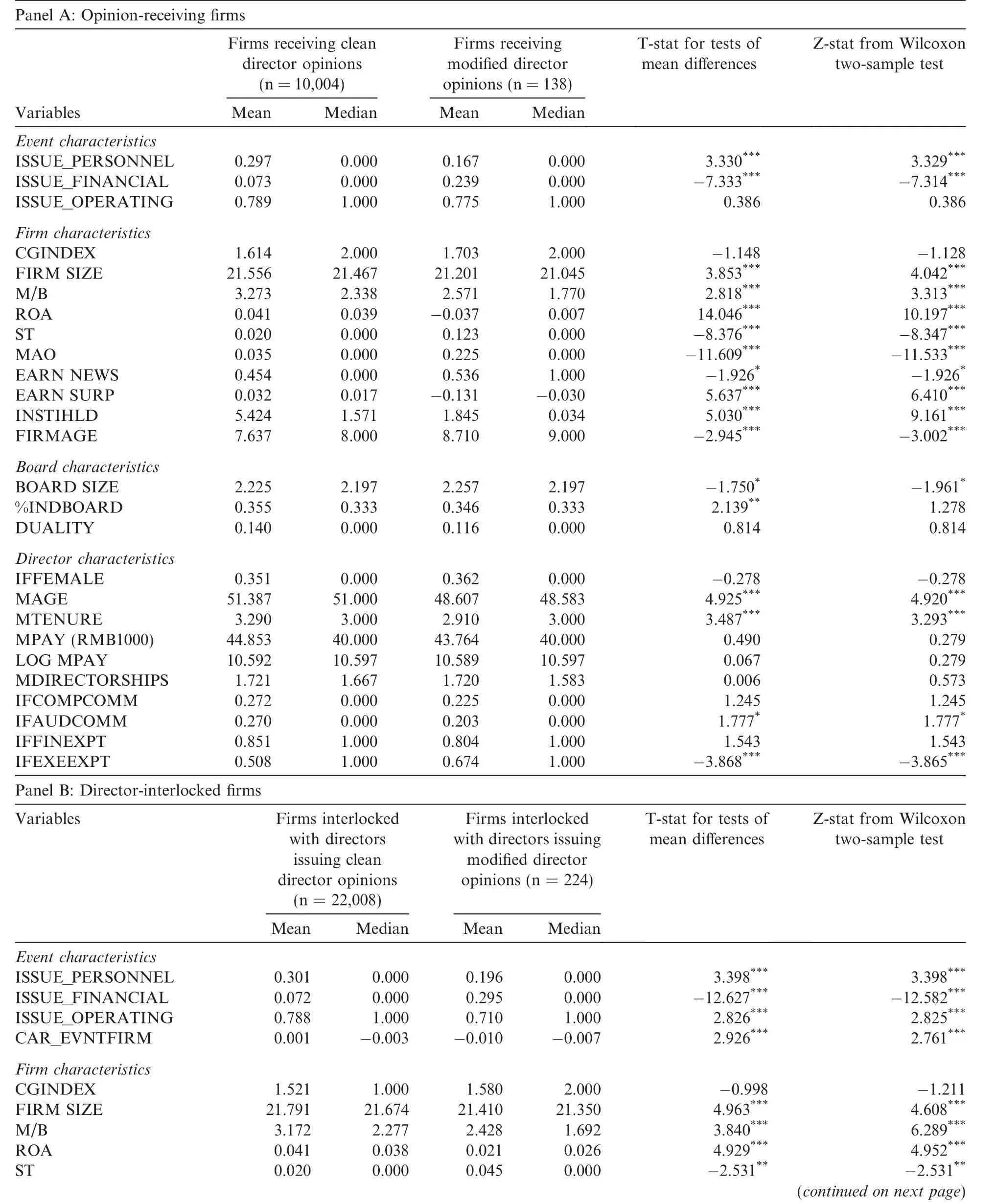

Table3 outlines the descriptive statistics of control variables for exploiting market reaction to independent directors’opinions.Panel A of Table 3 shows several significant mean differences in control variables between firms receiving clean director opinions and those receiving modified opinions.Notable differences are that the firms receiving modified opinions display,on average,poorer accounting performance,less institutional shareholdings,smaller firm size and greater likelihood of receiving modified audit opinions.Furthermore,compared with firms receiving clean director opinions,firms with directors who say ‘‘no” to controlling shareholders or managers are more likely to appoint independent directors who are younger,have more executive expertise and are more likely to sit in audit committees.In terms of median differences,the results are similar.

Panel A of Table 4 presents the multivariate analysis of abnormal returns using the sample of opinion receiving firms.Consistent with Tang et al.(2013),the regression in Column(1)indicates that,as expected,there is a significantly negative association between MDO_EVNTFIRM and the abnormal return around directors’opinion announcements.Columns(2)to(4)of Panel A present the regression results based on the subsamples of different opinion affairs.Column(4)shows that the estimated coefficient of MDO_EVNTFIRM is significantly negative when independent directors say ‘‘no” on operating issues.Although the coefficients of MDO_EVNTFIRM are not statistically significant on personnel issues in Column(2)and financial issues in Column(3),the sign of the coefficients is negative and consistent with the prediction.As for the control variables,EARN NEWSand INSTIHLD have significant effects on the abnormal returns when independent directors issue opinions.

4.3.Market reaction for director-interlocked firms

In this section,we conduct similar tests to those described in the previous section for firms interlocked with directors who issue opinions:

where all of the variable are defined in Appendix A.Proposal-fixed effects are included to control for the endogeneity that may arise from possibly omitted explanatory variables.

Panel B of Table 3 reveals a number of differences between firms interlocked with directors issuing clean reports and those interlocked with directors issuing modified reports.Firms interlocked with directors issuing modified director opinions are more likely to report poorer accounting performance,be smaller and have fewer independent directors or less institutional shareholding.Moreover,firms interlocked with directors who say ‘‘no” tend to appoint independent directors with shorter tenure,lower pay,more executive expertise and less experience in compensation and audit committees in their interlocking firms.The median differences are similar.

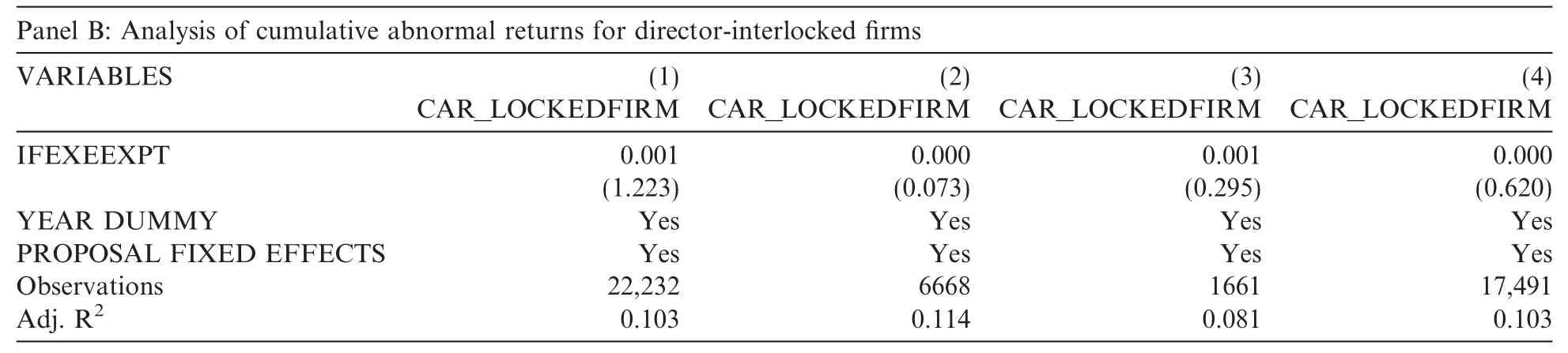

Panel B of Table 4 presents the regression results for CARs using the interlocking firms,which reveal a significantly positive association between CARs and the variable of interest,MDO_LOCKEDFIRM,which is set to 1 if the firm is interlocked with an independent director who issues a modified opinion and 0 otherwise.The coefficient of MDO_LOCKEDFIRM is0.015 in Column(1),which means that the firm value increases by 1.5%if the firm interlocks with MDO independent directors.The result supports the prediction of the repu-tation hypothesis.The coefficient of the interaction term between MDO_LOCKEDFIRM and CGINDEX is negative and significant at the 10%level,suggesting that the market reaction to modified opinion in interlocked firms tends to be less positive when the firms are heavily influenced by controlling shareholders.The coefficients of several control variables are also significant.For example,consistent with Fama and French(1992),the market-to-book ratio(M/B)is significantly negative.The coefficients of the abnormal return of opinion-receiving firms are significantly positive,which reveals stock synchronization between event firms and interlocking firms.Moreover,when we divide the sample into three parts according to the opinion affairs,the regression results are shown in Columns(2)to(4).We find that the coefficients of MDO_LOCKEDFIRM are almost similar to those in Column(1),although the coefficients lose their statistical significance in Columns(2)and(4).

Table 3 Descriptive statistics of the variables in the cumulative abnormal return analysis.

5.Board seats and modified independent director opinions

In this section,we examine whether modified independent director opinions affect their board positions.

5.1.Variable description

We use the indicator variable RETAIN_EVNTFIRM(RETAIN_LOCKEDFIRM)to measure director turnover in opinion-receiving firms(director-interlocked firms)and set it to 1 if a director appears in thesecond year’s directors list following the year he/she announces his/her opinion.Given the need to check directors’turnover rates over 2 years,we collect a subsample of 294 individual independent directors who issued modified director opinions from 2005 to 2010.We also examine any changes in board seats subsequent to the issuance of independent director opinions.We define CHGSEATS as the mean changes in board seats for the 2 years following the issuance of a director’s opinion.RETCHGSEATS measures the mean changesin board seats divided by the number of board seats in the year of opinion issuance.GAINSEATS is the net gain of new seats the independent director secures subsequent to saying ‘‘no.” The variable is set to 0 if the director does not gain any new seats.

Table 4 Multivariate analysis of cumulative abnormal returns.

Table 4(continued)

Table 4(continued)

Table 5 Univariate analysis of retaining directorships.

Table 6 Descriptive statistics of directorship analysis.

Table 6(continued)

Panel A of Table 5 presents the changes in directorships held by the 294 individual independent directors.Year zero refers to the modified opinion’s announcement year.The average director ships decrease persistently,from 1.59 directorships in year zero to 1.02 directorships in year two.In year zero,33.67%of directors hold more than one board seat,and this ratio decreases by more than 10–22.79%in year two.

Our main variables of interest are the indicator variables that differentiate between the independent directors who say ‘‘no” in the opinion-receiving(MDO_DIR)and director-interlocked(MDO_LOCKEDDIR)firms.

As discussed in Section 4,we control for several variables that the literature has shown to influence directorships at both the firm and director levels.First,we include CGINDEX in the regression to control for the entrenchment effects of large shareholders.As independent director turnover is highly related to CEO turnover,we also include an indicator of CEO turnover in the analysis(Fich and Shivdasani,2007).

Second,the regression also includes a set of director-specific attributes,including indicator variables such as whether the independent director is female(Adams and Ferreira,2009;Gul et al.,2011;Srinidhi et al.,2011),COMPCOMM and AUDCOMM if the director sits on the compensation committee or audit committee(Davidson et al.,1998;Srinivasan,2005)and FINEXPT and EXEEXPT if the director has any financial or executive expertise(DeFond et al.,2005).Other variables include director tenure(TENURE),whether some directors are serving their second term on the board(IFTERM 2),director pay(PAY)and the number of board positions held as an independent director(DIRECTORSHIPS).Following Fich and Shivdasani(2007),we also consider whether the director is a compensation or audit committee member in an opinion receiving firm(COMPCOMM_EVNTFIRM and AUDCOMM_EVNTFIRM,respectively)in the analysis of retaining directorships in interlocking firms.When investigating the changes in the board seats of individual directors,we calculate board meeting absence(ABSENCE),mean director remuneration(MPAY_INDIVIDUAL)and mean tenure(MTENURE_INDIVIDUAL)for each individual director.Table 6 reports the descriptive statistics of the control variables in the directorship analysis.

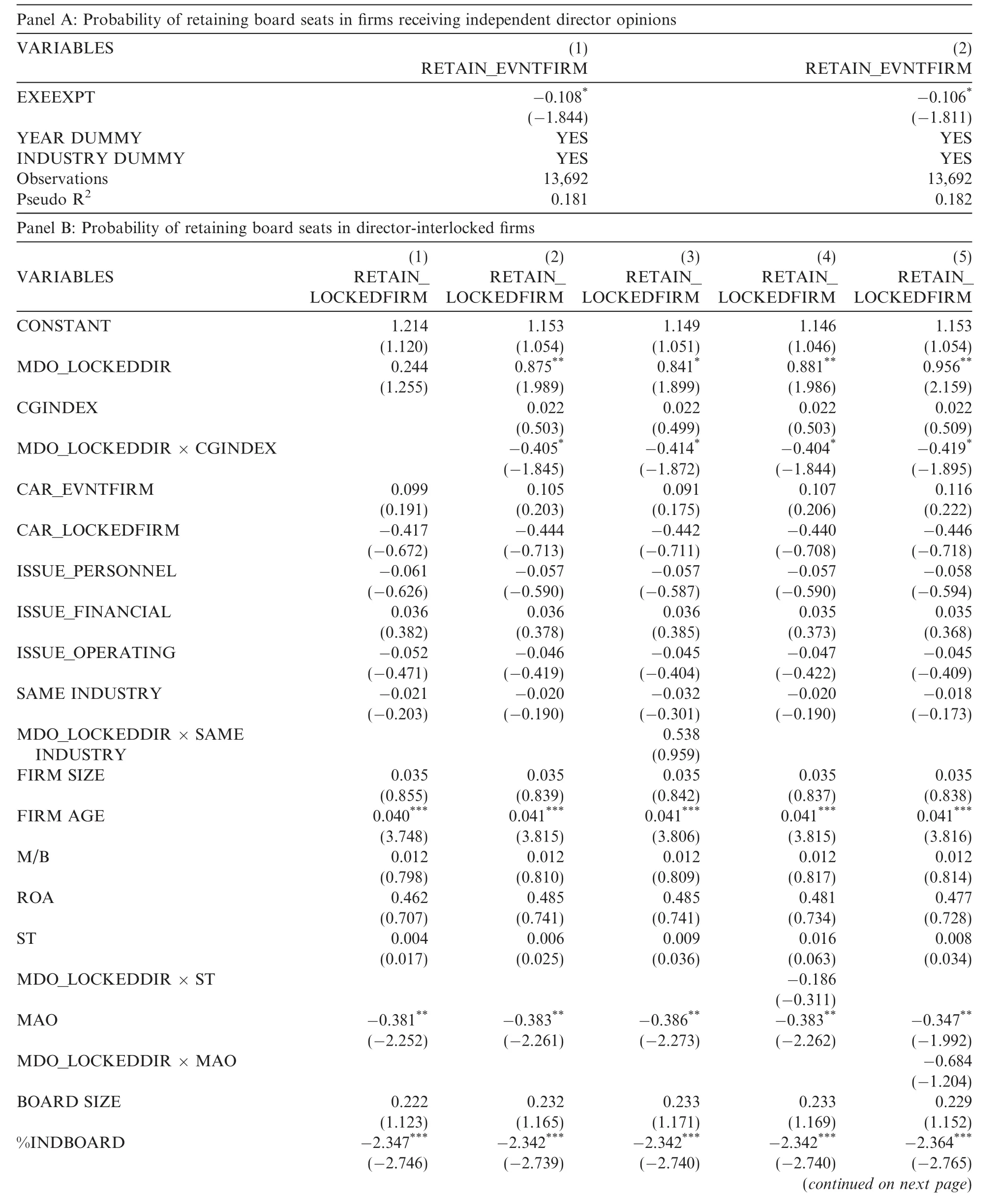

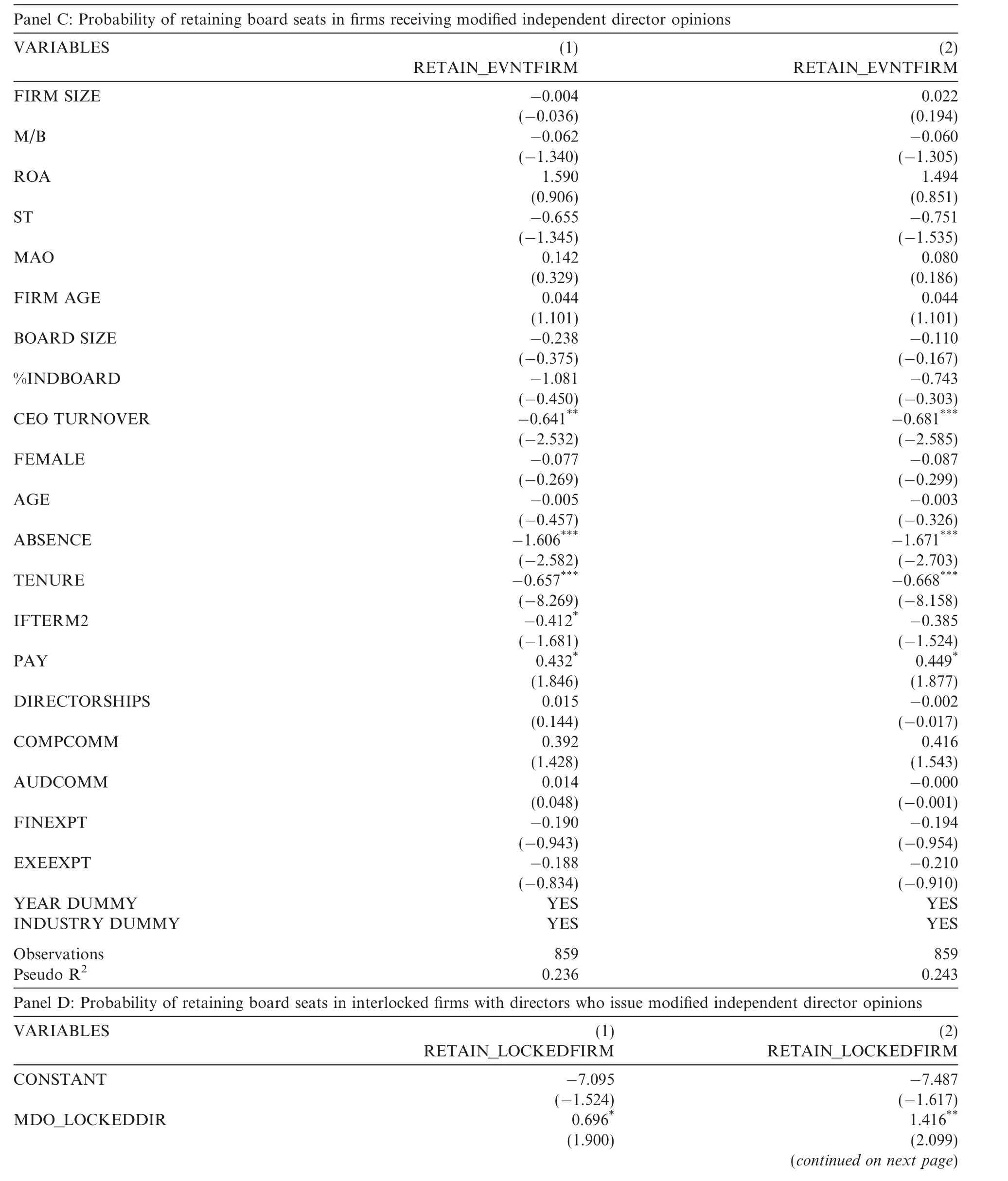

Table 7 Probability of retaining board seats.

Table 7(continued)

Table 7(continued)

Table 7(continued)

Table 7(continued)

Table 7(continued)

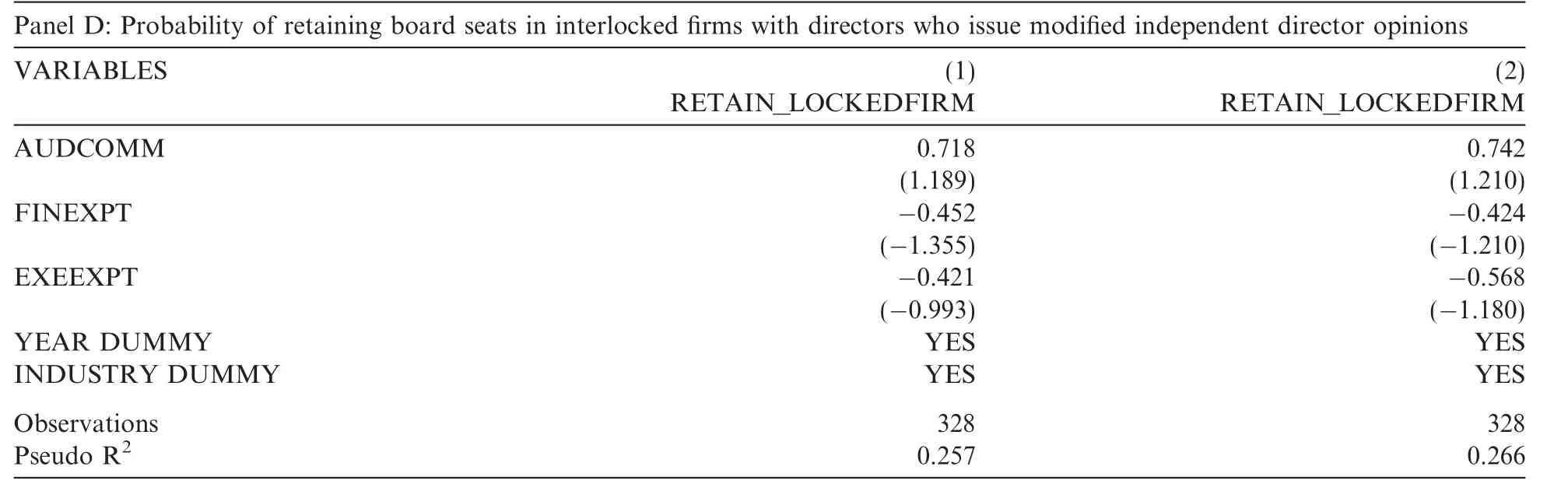

5.2.Probability of retaining directorships in opinion-receiving firms

In this section,we examine whether independent directors retain board seats after they issue opinions on corporate decisions.We first estimate the following regression:

where all of the variables are defined in Appendix A.

Panel A of Table 7 presents the logistic regression results of retaining directorships.Column(1)reveals a significantly negative association between retaining a board seat in an opinion-receiving firm and MDO_DIR,which suggests that directors who say ‘‘no” are more likely to leave opinion-receiving firms than the cohort that is friendly with the management on the board.

When the CGINDEX and its interaction with MDO_DIR are included in the regression,the coefficient of the interaction term is negative but not statistically significant,whereas the coefficient of MDO_DIR is still statistically significant.As expected,the estimated coefficients of FIRM SIZE and ROA are significantly positive,implying that independent directors are more likely to retain their board positions in firms that are bigger and perform better.The TENURE variable has negative effects on board positions,consistent with the Chinese practice that the tenure of an independent director cannot exceed 6 years.The coefficient of IFTERM 2 is statistically significant,which implies that if some other independent directors are in their second term,the independent director who issues opinions is more likely to retain his/her board seats.

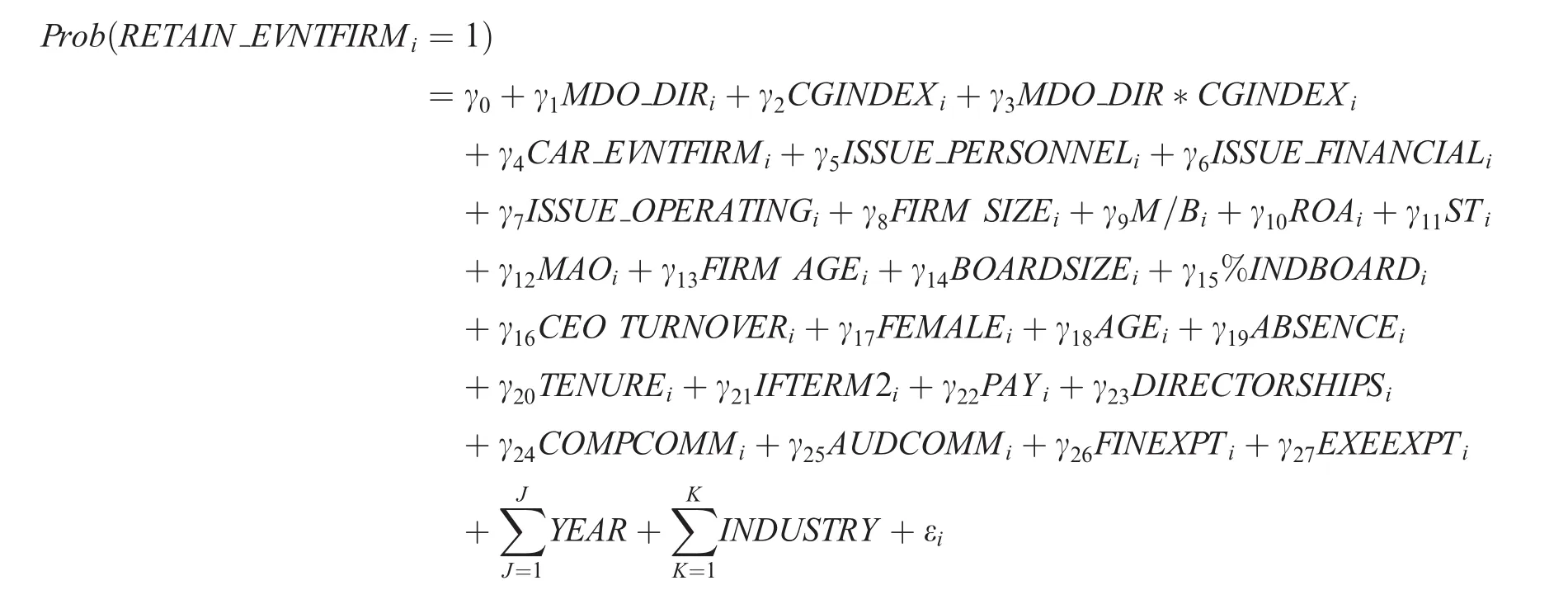

5.3.Probability of retaining directorships in director-interlocked firms

To test the probability of retaining directorships in director-interlocked firms,we use the following regression to analyze the sample of directors in interlocking firms:

Column(1)in Panel B of Table 7 shows that the estimated coefficient of MDO_LOCKEDDIR is positive but not statistically significant.When the governance index(CGINDEX)and its interaction with modified opinions(MDO_LOCKEDDIR)are included in the regression,MDO_LOCKEDDIR is significantly positive,indicating that an independent director who says ‘‘no” is more likely to retain his/her directorship in an interlocked firm.Interestingly,the interaction item in Column(2)is significantly negative,suggesting that an independent director who says ‘‘no” is more likely to lose his/her directorship in an interlocked firm if the firm is heavily influenced by the controlling shareholder.

To investigate the possibility of directors voluntarily reducing board seats in interlocked firms to manage litigation risk,when subjected to similar risk exposure in the same industry,we expand the equation to include the interaction item SAME INDUSTRY×MDO_LOCKEDDIR.We also check whether the main results hold by incorporating the interaction between financial difficulty and directors saying ‘‘no” in interlocked firms.Column(3)of Table 7 shows that SAME INDUSTRY is negatively associated with the likelihood of retaining directorship in director-interlocked firms,although the estimated coefficient is not significant.The interaction of SAME INDUSTRY is positive and insignificant,suggesting that directors who say ‘‘no”do not intend to reduce board seats in interlocked firms operating in the same industry.Columns(4)and(5)of Panel B show that the ST dummy is not significant but MAO is significantly negative,consistent with the alternative explanation that directors tend to reduce board seats when interlocked firms receive a modified audit report.However,we do not find evidence that directors who say ‘‘no” tend to cut their seats in interlocked firms.

Several control variables are important in determining whether board seats are retained in interlocked firms.Independent directors who serve in firms with longer listing histories and without CEO turnovers are more likely to retain board seats.If the firms have a lower percentage of independent directors or if the independent directors have shorter tenure,the probability of retaining directorships in director-interlocked firms increases.

The remainder of the analysis in Table 7 examines the probability of retaining a director who said ‘‘no”in other firms versus the probability of retaining other directors.Panel C presents the analysis of retaining board seats in firms receiving independent directors’opinions.As indicated in Column(1),the coefficient of MDO is significantly negative,suggesting that directors are more likely to leave the incumbent seat after they say ‘‘no”than directors who never say ‘‘no” in firms receiving modified opinions.Panel D of Table 7 presents the results using a sample of firms interlocked with directors who sit in firms receiving modified opinions.The indicators of SAME INDUSTRY,ST and MAO are all insignificant,indicating that the alternative explanation,that is,that directors tend to reduce board seats in interlocked firms to manage litigation risk,may not be a big concern.On the contrary,outspoken directors may even benefit by retaining their seats in the interlocked firms.

5.4.Changes in directorships following the issuance of modified director opinions

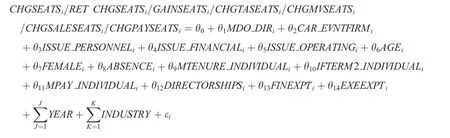

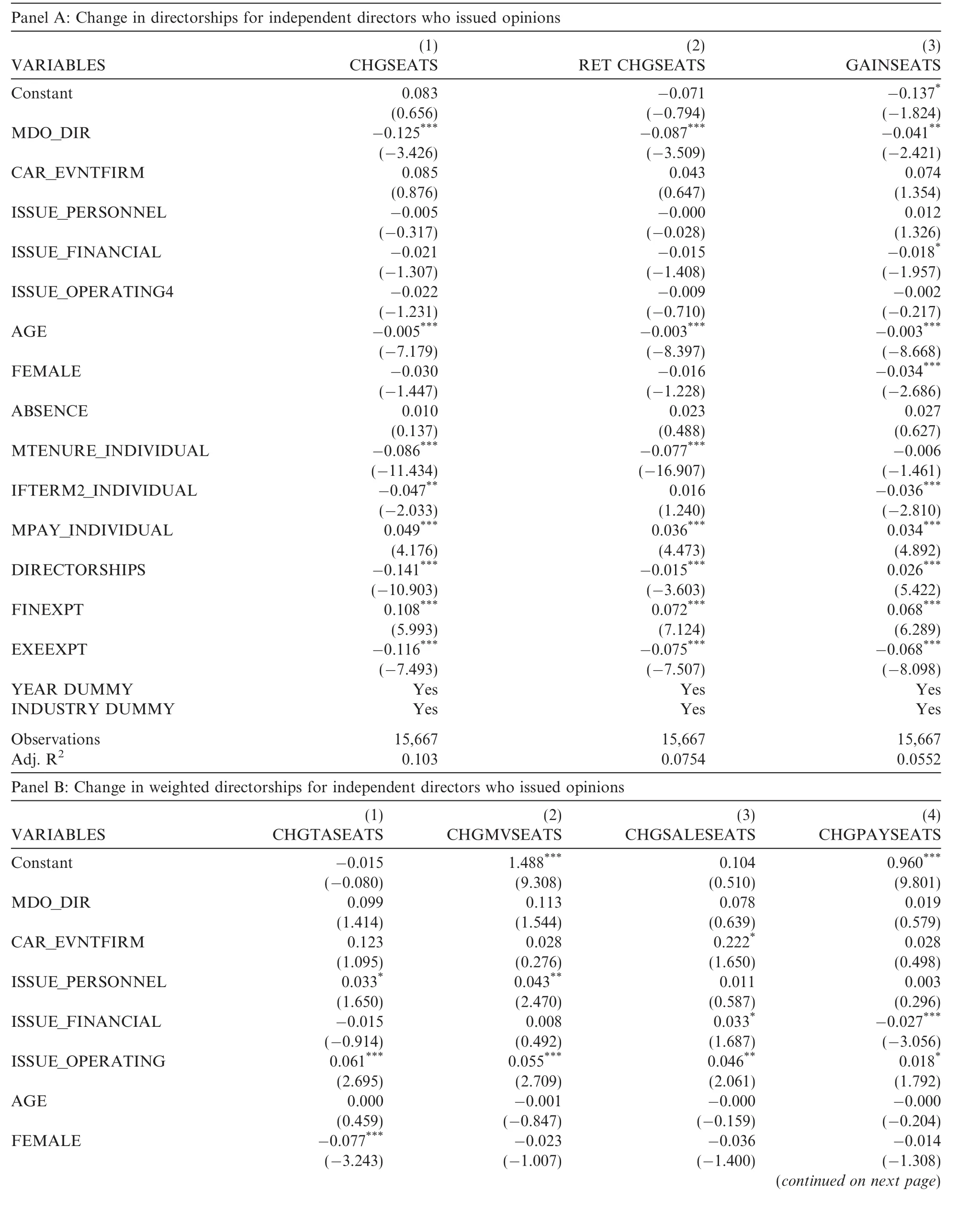

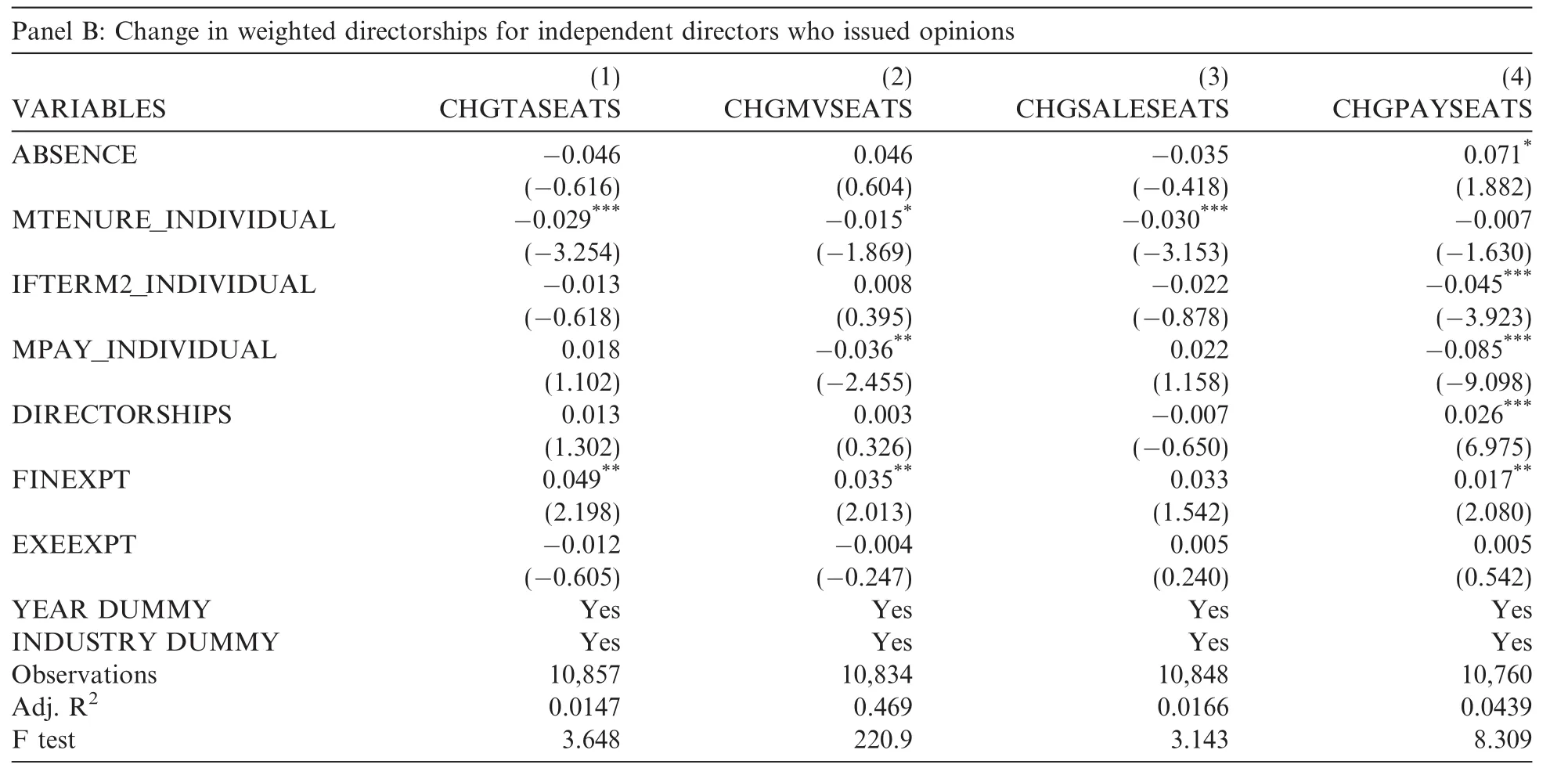

In this section,we track the change in directorships over a 2-year period following independent directors’issuance of director opinions.We estimate the following regression to analyze the reputation consequences of independent directors,with the dependent variables being CHGSEATS,RET CHGSEATS and GAINSEATS,all of which measure the changes in directorships in different ways(all of the variables are defined in Appendix A):3We do not control for firm-specific characteristics in the change in directorship regressions,as we are investigating the change in the total board seats held by an independent director after he/she issues an opinion.

According to the reputation hypothesis,we expect to find a positive relation between changes in board seats and modified independent director opinions.Table 8 reports the regression results for the three specifications.Contrary to the prediction of the reputation hypothesis,the results in Columns(1)to(3)show that MDO_-DIR’s estimated coefficients are negative and highly significant,implying that effective board monitoring is not rewarded through additional board appointments.Consistent with our expectation,the coefficient of AGE is significantly negative at the 1%level.MPAY_INDIVIDUAL is positively related to CHGSEATS,RET CHGSEATS and GAINSEATS,which indicates that independent directors with higher pay tend to have more board positions in the future.The estimated coefficient of FINEXPT is positive and significant,implying that independent directors with accounting expertise tend to have more board positions,which is consistent with the Chinese regulation that listed companies should appoint at least one independent director with an accounting background(CSRC,2001).

Table 8 Change in directorships for independent directors who issued opinions.

Table 8(continued)

It is conceivable that directors who say ‘‘no” may gain from their reputations by sitting in boards of larger firms despite holding fewer board seats.Panel B of Table8 sheds light on this possibility by examining changes in the weighted average of directorships using firms’total assets,market caps,sales and total director pay in the analysis regressions of directorship changes.The results indicate that the indicator of a director who says‘‘no” is positive and not statistically significant in all of the regressions across a variety of weighted averages of directorships.Although the coefficients are not significant,we cannot rule out the prediction that directors who say ‘‘no” may be rewarded with seating on the boards of larger firms.

6.Sensitivity tests

6.1.Alternative event window specification

We also use additional event windows to calculate the CARs around opinion announcements,including(0,+1)and(0,+2).The results are qualitatively the same when we use the CARs on alternative event windows.

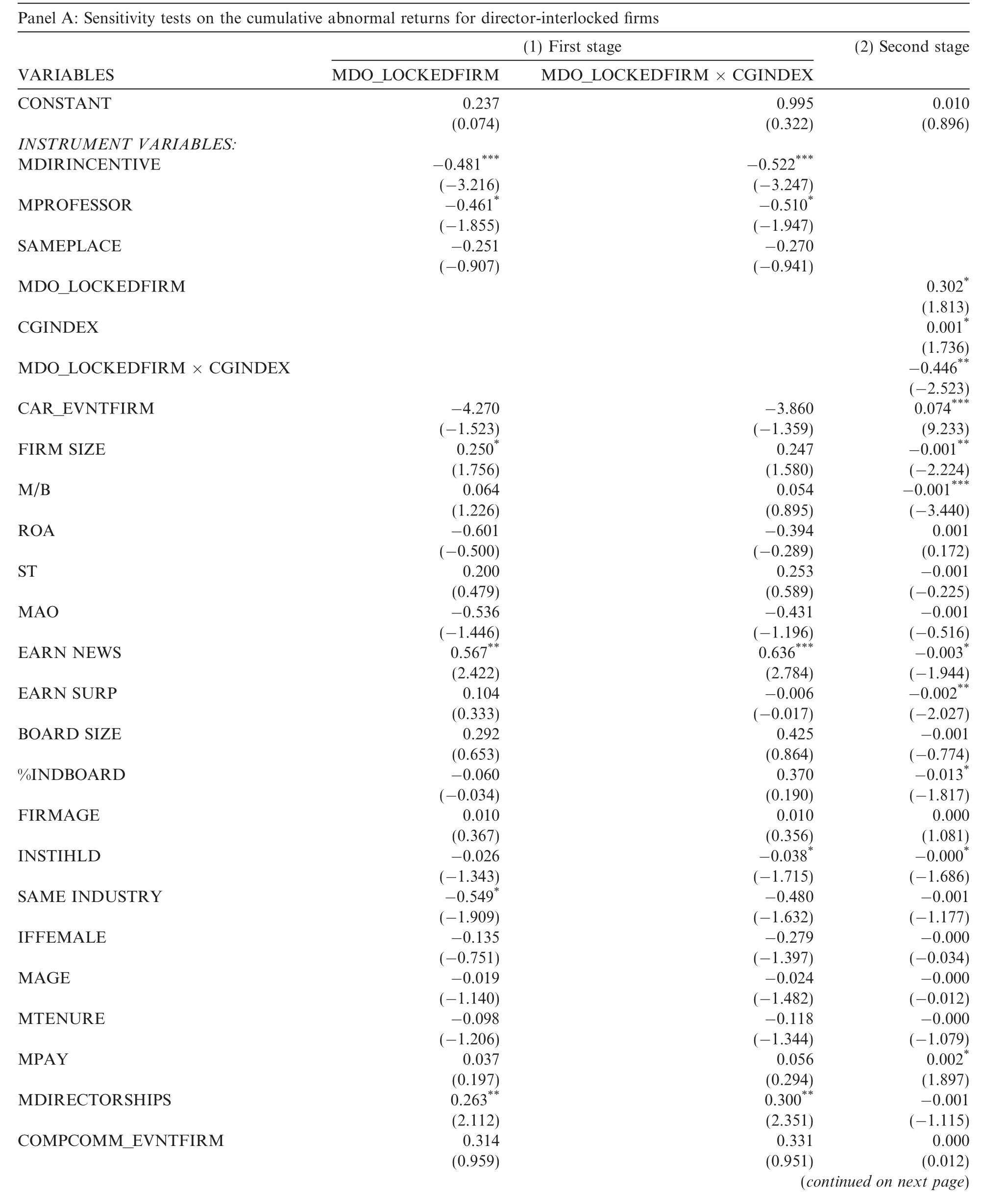

6.2.Endogeneity concern

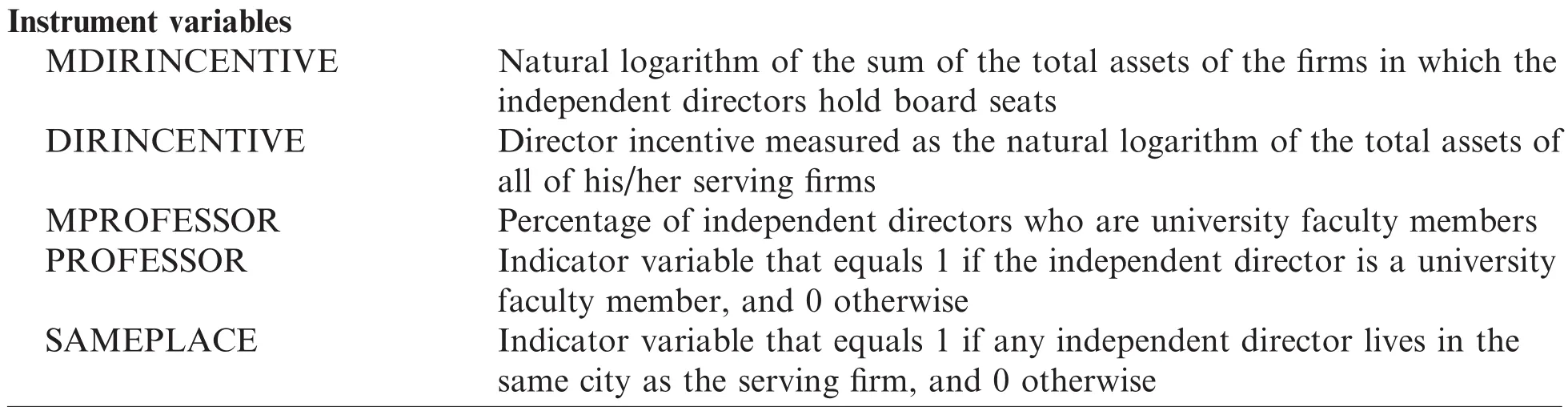

To avoid choice-based sample bias in our empirical test(Doyle et al.,2007),our main results are based on the unmatched sample of firms that received modified director opinions and those with clean director opinions.To mitigate the endogeneity concern that may arise from any omitted variables that are correlated with market reaction/director turnover and the probability of an independent director saying ‘‘no,” we take an instrumental variable approach in robustness tests to incorporate the determinants of independent directors’issuance of modified opinions.In the firm-level analysis,the first instrument we use is MDIRINCENTIVE,measured as the natural logarithm of the sum of the total assets of the firms in which the independent directorshold board seats.Masulis and Mobbs(2014)argue that firm size is a natural source of director reputation incentives,given that larger firms afford a director greater visibility,prestige,compensation and likelihood of obtaining additional directorships.Accordingly,directorships in firms of different sizes create differential incentives to monitor senior management closely.We expect the reputation incentives of independent directors to affect their propensity to say ‘‘no.” The second instrument in the firm-level analysis is MPROFESSOR,the percentage of independent directors who are university faculty members.Francis et al.(2013)find that academic directors are effective monitors and play an important governance role through their advising and monitoring functions.The third instrument we use in the firm-level analysis is SAMEPLACE,an indicator set to 1 if any independent director lives in the samecity as the serving firm,as Alam et al.(2014)find that geographic distance between directors and corporate headquarters is related to information acquisition and board decisions.In the director-level analysis,the instruments are the natural logarithm of the total assets of the firms in

which the independent director holds board seats(DIRINCENTIVE);the indicator,which is set to 1 if the independent director is a faculty member(PROFESSOR);and SAMEPLACE.In the first stage,we add the instrument to the logit model to estimate an independent director’s propensity to issue a modified opinion,with all independent variables from the second stage serving as control variables.As there are three groups of tests,including market reaction,retaining directorships and change in directorships,three sets of first-stage regressions are presented in Table 9.

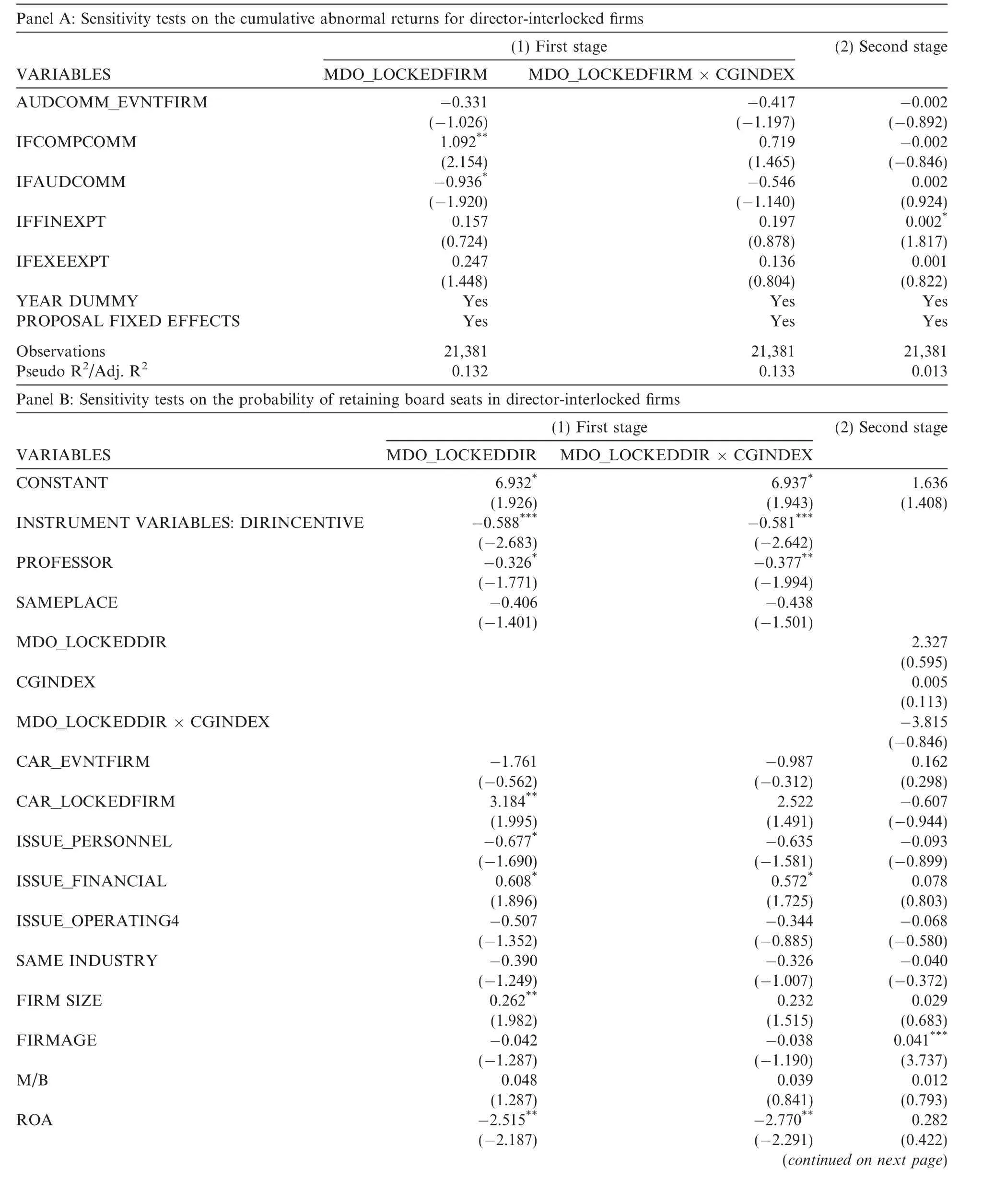

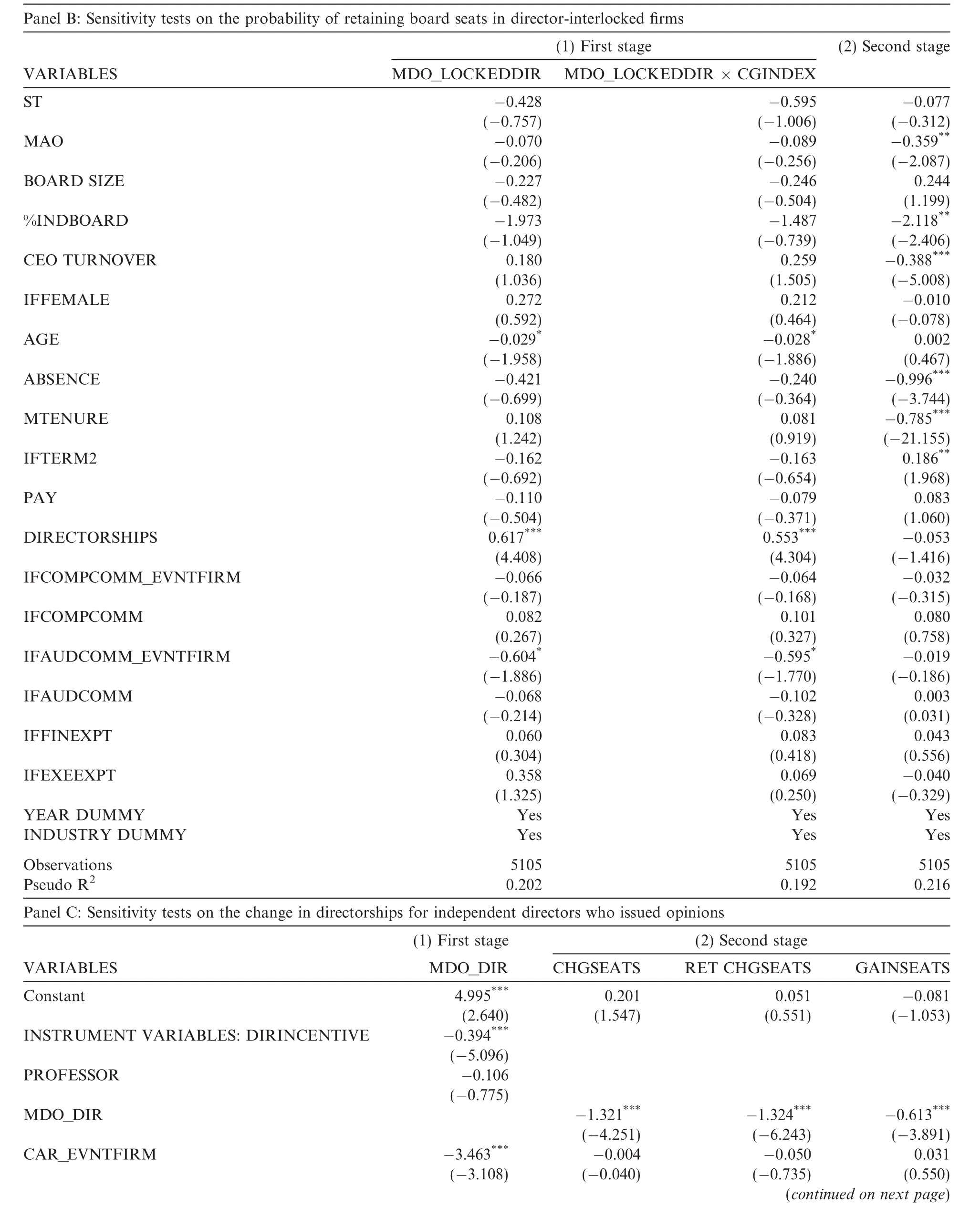

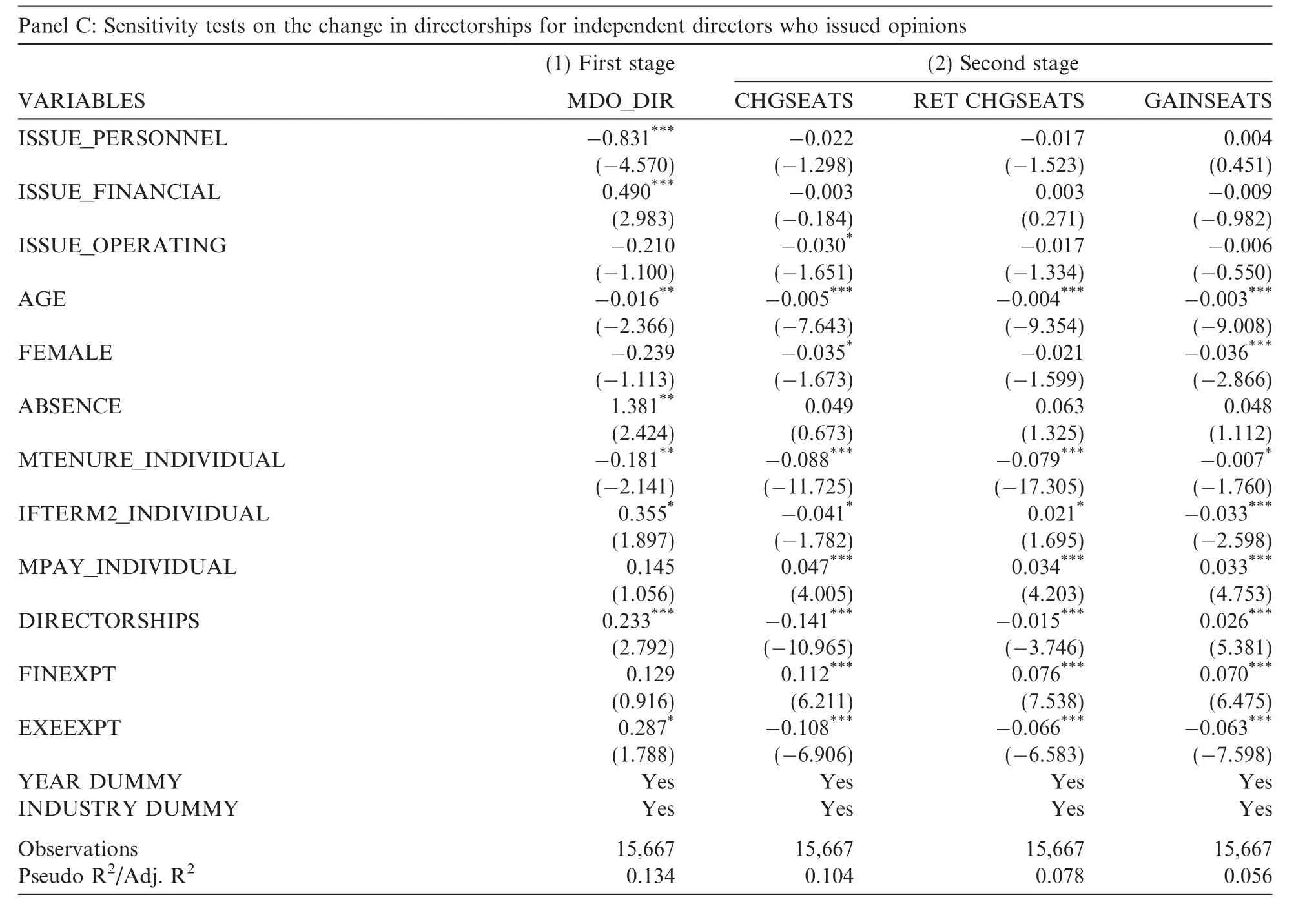

Table 9 Sensitivity tests on endogeneity.

Table 9(continued)

Table 9(continued)

Table 9(continued)

Next,we use the predicted probability from the first stage to replace the MDO indicators in the second stage regressions.As MDO*CGINDEX appears in the CAR regression and the tests on retaining directorships,MDO*CGINDEX is also estimated in the first stage and the predicted value is included in the second-stage regressions.As we primarily focus on the reputation of or endogenous hypothesis for the independent director,we focus only on the tests for interlocked firms.

Table 9 presents additional regressions with instrument variables.In the first-stage regressions in Panels A to C of Table 9,the director incentive variable appears to be negatively correlated with the director’s propensity to issue modified opinions,which is inconsistent with Masulis and Mobbs(2014).One possible explanation is that independent directors with more board seats may tend to keep silent in board meetings,as they have more to lose when standing up to corporate insiders.Panel A of Table9 reports the results of the market reaction to director opinions in interlocked firms.As expected,the instrumented MDO_LOCKEDFIRM variable is significantly positively associated with CARs,and the instrumented MDO_LOCKEDFIRM*CGINDEX variable is significantly negatively associated with CARs.Panels B and C of Table 9 show the tests for the probability of retaining board seats and the change in directorships.Although the probability of retaining board seats in director-interlocked firms is not significant,we find qualitatively similar results that the instrumented MDO_DIR is negatively associated with the change in directorships in the 2 years subsequent to issuing modified director opinions.The preceding sensitivity tests show that our main results in Sections 4 and 5 are robust.

6.3.Interlocking firms that also received modified independent director opinions

If some interlocking firms in our sample also received modified independent director opinions on a date close to the event date,the resu4We thank the reviewer for bringing this point to our attention.lts in Table 7 that pertain to retaining board seats in director-interlocked firms may be biased to our findings. To address this concern,we conduct a sensitivity test by excluding the interlocking firms that also received modified independent director opinions within a 5-year event window(t-2 to t+2)and rerun the regressions in Panels B and D of Table 7.In so doing,we delete 21 distinct interlocking firms and lose 132 board-year observations.The results remain qualitatively the same.

7.Conclusions

We examine the stock and labor market effects associated with independent directors’issuance of director opinions in the Chinese market.We find that the market reacts negatively to modified director opinions,but that director-interlocked firms exhibit positive stock returns around the opinion announcement dates.We further find that independent directors are more likely to lose directorships after they issue modified opinions and less likely to gain new board appointments after they say ‘‘no” in board meetings.Our findings suggest that although the disclosure of independent board monitoring is informative after controlling for alternative explanations in previous studies,the reputation of independent monitoring does not reward individual independent directors by increasing their future directorships.Overall,we enrich the director reputation literature by examining the consequences of independent directors’active monitoring of the stock market and labor market.Although our results are based on a small sample of modified opinions of independent directors in China,they may have important implications for the regulators of emerging markets,where independent directors play a crucial role in protecting the interests of minority shareholders.

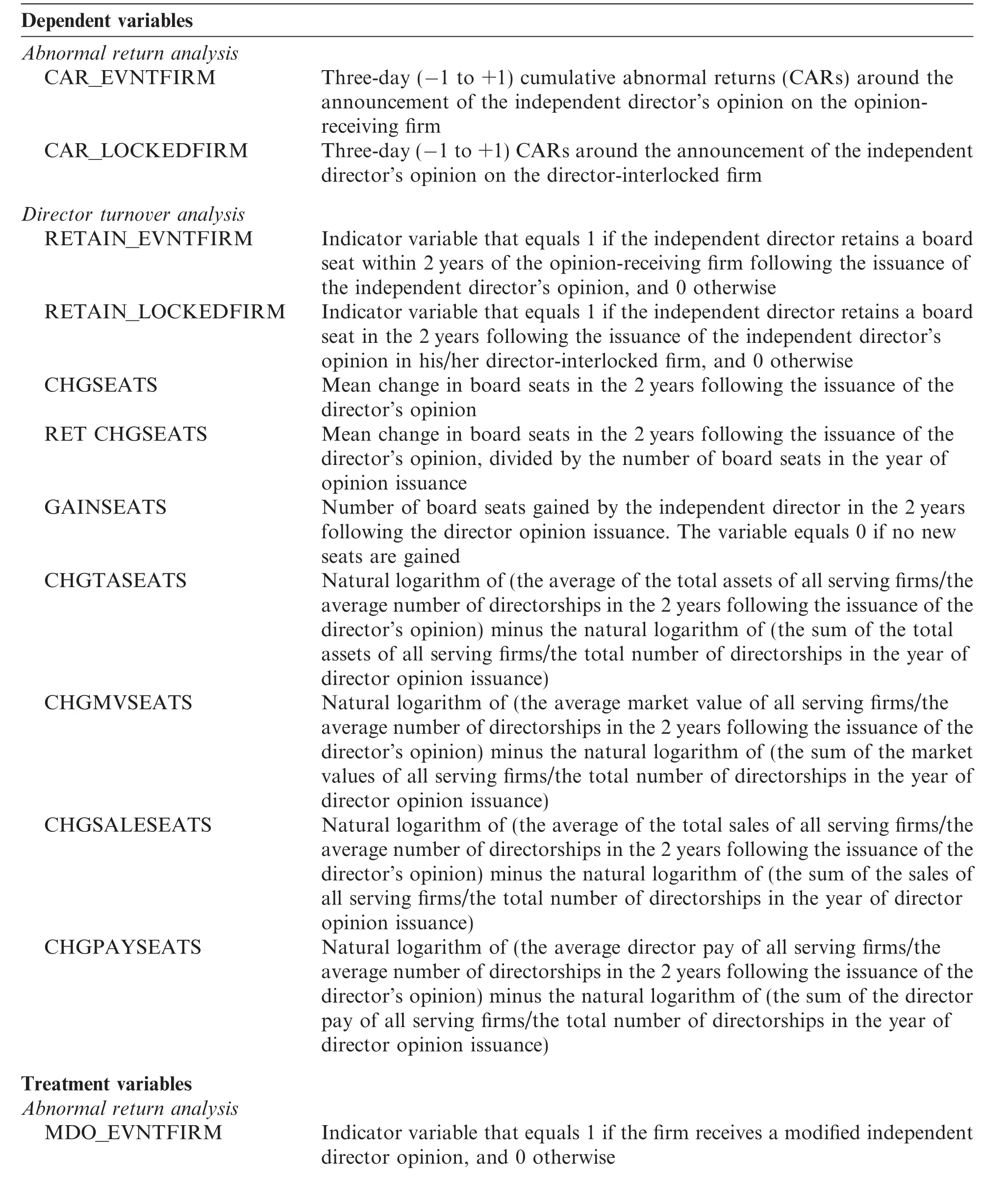

Appendix A.Variable definitions

MDO_LOCKEDFIRM Indicator variable that equals 1 if the firm is interlocked with an independent director who issues a modified director opinion,and 0 otherwise Director turnover analysis MDO_DIR Indicator variable that equals 1 if the independent director issues a modified director opinion,and 0 otherwise MDO_LOCKEDDIR Indicator variable that equals 1 if the independent director issues a modified director opinion to the director-interlocked firm,and 0 otherwise Control variables Event characteristics ISSUE_PERSONNEL Indicator variable that equals 1 if the independent director’s opinion is issued toward a board resolution on personnel issues(e.g.,appointing or discharging top executives and managerial compensation),and 0 otherwise ISSUE_FINANCIAL Indicator variable that equals 1 if the independent director’s opinion is issued toward a board resolution on financial reporting and auditing issues,and 0 otherwise ISSUE_OPERATING Indicator variable that equals 1 if the director’s opinion is on operating issues other than personnel,financial reporting and auditing issues,and 0 otherwise Firm and board characteristics FIRM SIZE Natural logarithm of total assets M/B Market value of equity/book value of equity ROA Net income/total assets ST Indicator variable that equals 1 if the firm is given special treatment status,and 0 otherwise MAO Indicator variable that equals 1 if the firm receives a modified audit opinion,and 0 otherwise FIRM AGE Number of years the firm’s stock has traded on the Shanghai or Shenzhen stock exchange EARN NEWS Indicator variable that equals 1 if the firm announces earnings in the same window(-1 to+1)as the independent director’s opinion,and 0 otherwise EARN SURP Most recently announced earnings minus the earnings four quarters ago,divided by the market value of equity SAME INDUSTRY Indicator variable that equals 1 if the director-interlocked firm is in the same industry as the opinion-receiving firm,and 0 otherwise BLOCK Indicator variable that equals 1 if the percentage of ownership held by the largest shareholder is more than the median,and 0 otherwise CONTROL DISPERSION Indicator variable that equals 1 if the ultimate controlling shareholder’s control rights do not equal the shareholder’s ownership,and 0 otherwise INSTIHLD Percentage of ownership in the firm held by institutional investors LESSINSTIHLD Indicator variable that equals 1 if the percentage of ownership held by institutional investors is less than the median,and 0 otherwise DUALITY Indicator variable that equals 1 if the chairman of the board is also the CEO,and 0 otherwise CGINDEX Composite index calculated by summing up BLOCK,CONTROL DISPERSION,LESSINSTIHLD and CEO DUALITY(ranging from 0 to 4)CEO TURNOVER Indicator variable that equals 1 if the CEO or chairman leaves the office in the 2 years following the director opinion announcement,and 0 otherwise

BOARD SIZE Natural logarithm of the number of board members%INDBOARD Percentage of the board members who are independent directors Director characteristics FEMALE Indicator variable that equals1 if the independent director is female,and 0 otherwise IFFEMALE Indicator variable that equals 1 if at least one independent director of a company is female,and 0 otherwise TENURE Years of service as an independent director on the firm’s board MTENURE Mean years of service as an independent director for all independent directors on the firm’s board MTENURE_INDIVIDUAL Mean years of service asan independent director across all of his/her board positions as an independent director IFTERM 2 Indicator variable that equals 1 if at least one independent director has served the firm for more than 3 years,and 0 otherwise IFTERM 2_INDIVIDUAL Indicator variable that equals 1 if an independent director has served for more than 3 years in any of his/her serving firms,and 0 otherwise AGE Age of the independent director MAGE Mean age of all independent directors on the firm’s board PAY Natural logarithm of annual director remuneration MPAY Natural logarithm of mean annual director remuneration for all independent directors on the firm’s board MPAY_INDIVIDUAL Natural logarithm of mean annual director remuneration for an independent director across all of his/her serving firm boards as an independent director ABSENCE Percentage of absences to total number of board meetings DIRECTORSHIPS Number of board seats held by a person in all of his/her serving companies as an independent director MDIRECTORSHIPS Mean number of board seatsheld by all independent directors on the firm’s board COMPCOMM Indicator variable that equals 1 if the opinion-issuing director is a member of the firm’s compensation or nomination committee,and 0 otherwise COMPCOMM_EVNTFIRM Indicator variable that equals 1 if the interlocked independent director is a member of the opinion-receiving firm’s compensation or nomination committee,and 0 otherwise IFCOMPCOMM Indicator variable that equals 1 if any opinion-issuing director sits on the compensation committee of the board,and 0 otherwise AUDCOMM Indicator variable that equals 1 if the opinion-issuing director is a member of the firm’s audit committee,and 0 otherwise IFAUDCOMM Indicator variable that equals 1 if any opinion-issuing director sits on the audit committee of the board,and 0 otherwise AUDCOMM_EVNTFIRM Indicator variable that equals 1 if the interlocked independent director is a member of the opinion-receiving firm’s audit committee,and 0 otherwise FINEXPT Indicator variable that equals 1 if the opinion-issuing director has financial expertise,and 0 otherwise IFFINEXPT Indicator variable that equals 1 if any independent directors of the firm have financial expertise,and 0 otherwise EXEEXPT Indicator variable that equals1 if the opinion-issuing director has executive expertise,and 0 otherwise IFEXEEXPT Indicator variable that equals 1 if any independent directors of the firm have executive expertise,and 0 otherwise

Instrument variables MDIRINCENTIVE Natural logarithm of the sum of the total assets of the firms in which the independent directors hold board seats DIRINCENTIVE Director incentive measured as the natural logarithm of the total assets of all of his/her serving firms MPROFESSOR Percentage of independent directors who are university faculty members PROFESSOR Indicator variable that equals 1 if the independent director is a university faculty member,and 0 otherwise SAMEPLACE Indicator variable that equals 1 if any independent director lives in the same city as the serving firm,and 0 otherwise

Adams,R.,Ferreira,D.,2009.Women in theboardroom and their impact on governance and performance.J.Financ.Econ.94(2),291–309.

Agrawal,A.,Chen,M.A.,2011.Boardroom brawls:an empirical analysis of disputes involving directors.Available at SSRN:http://ssrn.com/abstract=1362143 or https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1362143.

Alam,Z.S.,Chen,M.A.,Ciccotello,C.S.,Ryan,H.E.,2014.Does the location of directors matter?Information acquisition and board decisions.J.Financ.Quantitative Anal.,forthcoming

Bai,C.E.,Liu,Q.,Lu,J.,Song,F.M.,Zhang,J.,2004.Corporate governance and market valuation in China.J.Compar.Econ.32,599–616.

Brickley,J.,Coles,J.,Terry,R.,1994.Outside directors and the adoption of poison pills.J.Financ.Econ.35,371–390.

Bushee,B.J.,1998.The influence of institutional investors on myopic R&D investment behavior.Account.Rev.73(3),305–333.

Byrd,J.,Hickman,K.,1992.Do outside directors monitor managers?Evidence from tender offer bids.J.Financ.Econ.32,195–221.

Chung,R.,Firth,M.,Kim,J.,2002.Institutional monitoring and opportunistic earnings management.J.Corpor.Finance 8(1),29–48.

Conyon,M.J.,He,L.,2011.Executive compensation and corporate governance in China.J.Corpor.Finance 17,1158–1175.

Cornett,M.M.,Marcus,A.J.,Saunders,A.,Tehranian,H.,2007.The impact of institutional ownership on corporate operating performance.J.Bank.Finance 31(6),1771–1794.

CSRC,1997.Guidelines for the articles of association of listed companies(in Chinese).

CSRC,2001.Guiding opinion on establishing an independent director system in listed companies(in Chinese).

CSRC,2005.Circular of issuing the provisions on strengthening the protection of the rights and interests of the general public shareholders(in Chinese).

Davidson III,W.N.,Pilger,T.,Szakmary,A.,1998.Golden parachutes,board and committee composition,and shareholder wealth.Financ.Rev.33,17–32.

DeFond,M.L.,Hann,R.N.,Hu,X.,2005.Does the market value financial expertise on audit committees of boards of directors?J.Account.Res.43(2),153–193.

Dey,A.,2008.Corporate governance and agency conflicts.J.Account.Res.46(5),1143–1181.

Doyle,J.,Ge,W.,McVay,S.,2007.Determinants of weaknesses in internal control over financial reporting.J.Account.Econ.44,193–233.

Duchin,R.,Matsusaka,J.G.,Ozbas,O.,2010.When are independent directors effective?J.Financ.Econ.96,195–214.

Fahlenbrach,R.,Low,A.,Stulz,R.M.,2010.The dark side of independent directors:do they quit when they are most needed?Available at SSRN:http://www.ssrn.com/abstract=1585192.

Faleye,O.,Hoitash,R.,Hoitash,U.,2011.The costs of intense board monitoring.J.Financ.Econ.101,160–181.

Fama,E.F.,French,K.R.,1992.The cross-section of expected stock returns.J.Finance 47(2),427–465.

Fama,E.F.,Jensen,M.C.,1983.Separation of ownership and control.J.Law Econ.26,301–325.

Fich,E.M.,Shivdasani,A.,2007.Financial fraud,director reputation,and shareholder wealth.J.Financ.Econ.86,306–336.

Francis,B.,Hasan,I.,Wu,Q.,2013.Professors in the boardroom:is there an added value for academic directors?Financ.Manage.,forthcoming

Gilson,S.C.,1990.Bankruptcy,boards,banks,and block holders.J.Financ.Econ.27,355–387.

Gul,F.,Srinidhi,B.,Ng,A.,2011.Does board gender diversity improve the informativeness of stock prices?J.Account.Econ.51(3),314–338.

Harford,J.,2003.Takeover bids and target director’sincentives:the impact of a bid on director’s wealth and board seats.J.Financ.Econ.69,51–83.

Hermalin,B.E.,Weisbach,M.S.,2003.Boards of directors as an endogenously determined institution:a survey of the economic literature.Econ.Policy Rev.9,7–26.

Jiang,G.,Wang,H.,2008.Should earnings thresholds be used as delisting criteria in stock market?J.Account.Public Policy 27(5),409–419.

Jiang,W.,Wan,H.,Zhao,S.,2016.Reputation concerns of independent directors:evidence from individual director voting.Rev.Financ.Stud.29(3),655–696.

Larcker,D.F.,Richardson,S.A.,Tuna,I.,2007.Corporate governance,accounting outcomes,and organizational performance.Account.Rev.82(4),963–1008.

Li,B.,2004.Effective monitoring saves independent directors from legal liability.Shanghai Securities News,July 1.

Lin,K.,Piotroski,J.D.,Yang,Y.G.,Tan,J.,2012.Voice or exit?Independent director decisions in an emerging economy.Available at SSRN:http://ssrn.com/abstract=2166876 or https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2166876.

Masulis,R.W.,Mobbs,S.,2014.Independent director incentives:where do talented directors spend their limited time and energy?J.Financ.Econ.111(2),406–429.

Richardson,S.,2005.Discussion of consequences of financial reporting failure for independent directors:evidence from accounting restatements and audit committee members.J.Account.Res.43(2),335–342.

Shivdasani,A.,Yermack,D.,1999.CEO involvement in the selection of new board members:an empirical analysis.J.Finance LIV 5,1829–1853.

Srinidhi,B.,Gul,F.A.,Tsui,J.,2011.Female directors and earnings quality.Contemp.Account.Res.28(5),1610–1644.

Srinivasan,S.,2005.Consequences of financial reporting failure for independent directors:evidence from accounting restatements and audit committee members.J.Account.Res.43(2),291–334.

Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress,2005.Company Law of the People’s Republic of China.

Tang,X.,Du,J.,Hou,Q.,2013.The effectiveness of the mandatory disclosure of independent directors’opinions:empirical evidence from China.J.Account.Public Policy 32(3),89–125.

Vafeas,N.,1999.Board meeting frequency and firm performance.J.Financ.Econ.53,113–142.

Weisbach,M.,1988.Independent directors and CEO turnover.J.Financ.Econ.20,431–460.

Yao,Y.,Xu,L.,Liu,Z.,2010.Taking away the voting powers from controlling shareholders:evidence from the Chinese securities market.J.Int.Financ.Manage.Account.21(3),187–219.

Yermack,D.,2004.Remuneration,retention,and reputation incentives for independent directors.J.Finance 59(5),2281–2308.

Yuan,R.L.,Xiao,J.Z.,Zou,H.,2008.Mutual funds’ownership and firm performance:evidence from China.J.Bank.Finance 32(8),1552–1565.

China Journal of Accounting Research2018年2期

China Journal of Accounting Research2018年2期

- China Journal of Accounting Research的其它文章

- Can material asset reorganizations affect acquirers’debt financing costs?–Evidence from the Chinese Merger and Acquisition Market☆

- Executive turnover in China’s state-owned enterprises:Government-oriented or market-oriented?

- Religious atmosphere and the cost of equity capital:Evidence from China