Towards an evaluation of alcoholic liver cirrhosis and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease patients with hematological scales

Agata Michalak, Halina Cichoz-Lach, Matgorzata Guz, Joanna Kozicka, Marek Cybulski, Witold Jeleniewicz,Andrzej Stepulak

Abstract

Key Words: Hematological markers; Alcoholic liver cirrhosis; Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio; Mean platelet volume-to-platelet-ratio

INTRODUCTION

A reliable noninvasive assessment of liver fibrosis remains a key goal in the field of hepatology. Liver biopsy is still perceived as a gold standard, however elastography in ultrasound or magnetic resonance mode have gained importance. Despite a great advance in the development of imaging techniques, simple blood surrogates in liver fibrosis would be the most appreciated diagnostic tools. A new potential player has been arising among direct and indirect markers of liver fibrosis for several years—hematological parameters. The utility of hematological indices definitely exceeded differential diagnosis of anemia or inflammatory process. It came out several years ago that routinely used parameters, like neutrophil (NEU)-to-lymphocyte (LYM) ratio (NLR), platelet (PLT)-to-LYM ratio (PLR) and mean PLT volume (MPV)-to-PLTratio (MPR) can be applied as markers of the prognosis in cancer, inflammatory bowel disease and cardiovascular patients. Some reports proved their involvement in the course of liver disorders, too[1-4]. Nevertheless, they are present in subsequent surveys rather than in everyday clinical practice. A vast majority of studies explored a role of NLR and PLR in the decompensation of liver fibrosis or the development of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) due to a tight linkage between liver pathologies and inflammation. Moreover, MPR was described in a single study as a predictor of liver fibrosis[5-9]. But available data on their role in the course of liver disorders are still scanty and unclear. Subsequently, a potential role of hematological indices has been poorly explored in the course of liver steatosis.

For these reasons we decided to explore NLR, PLR and MPR role in alcohol-related liver cirrhosis (ALC) and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) patients and to find out if there are any dependences between these hematological indices and serological (indirect and direct) markers of liver fibrosis. To the best of our knowledge, correlations between aforementioned hematological indices and serological markers of liver fibrosis have not been explored in a single study, yet and PLR has not been explored in NAFLD population, either. Because of a great worldwide clinical significance of ALC and NAFLD we decided to explore this group of patients. According to already collected data, a potential value of hematological indices in the populations of patients with ALC and NAFLD is poorly explored.Moreover, it appears to be the first study on Polish patients, assessing the relationships between hematological markers and serological indices of liver fibrosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The local ethics committee of the Medical University of Lublin approved the study (No. KE-0254/86/2016) and all patients signed an informed written consent in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration for the procedures they underwent.

Study population and research design

This study assessed 302 persons: 142 patients with ALC, 92 with NAFLD and 68 healthy volunteers in control group. Table 1 presents clinical features of study population. The diagnosis of liver cirrhosis was based on commonly used criteria. The presence of portal hypertension was proved in the doppler mode abdominal ultrasound examination (diameter of portal vein ≥ 13 mm) and other potential reasons of existing portal hypertension were excluded. All ALC patients underwent panendoscopy of the gastrointestinal tract — in 126 persons varices of the esophagus/stomach in the different stage were found. Ninety-two people were diagnosed with ascites and 84 of them underwent paracentesis. The presence of hepatic encephalopathy and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis were excluded in the whole group. All participants included to the survey gained 0/9 points in clinical hepatic encephalopathy staging scale (CHESS) scale. Alcoholic background of liver cirrhosis (LC) was diagnosed according to the proved daily intake of pure ethanol exceeding 30 g. A history of alcohol abuse was obtained directly from the patients or their family members. Moreover, all enrolled in the study ALC patients presented positive result of CAGE test. A diagnosis of NAFLD was established due to the history, physical examination, laboratory testing, and ultrasound imaging. A daily alcohol consumption did not exceed 20 g in men and 10 g in women. Certain diseases that can lead to steatosis (hepatobiliary infections, celiac disease, Wilson's disease, and alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency) have been excluded. Twenty-two persons were diagnosed with diabetes mellitus type 2. People with diabetes mellitus type 1 were excluded from the study. None of the patients presented impaired fasting glucose. Forty-six NAFLD patients were found to have arterial hypertension and metabolic syndrome was diagnosed in 84 persons. Viral, cholestatic and autoimmune liver disorders together with the presence of clinically significant inflammatory process were excluded in all participants. Antinuclear antibody (ANA), antimitochondrial antibody (AMA), anti-smooth muscle antibodies (ASMA), liver-kidney microsome type 1 (anti-LKM-1) antibodies, hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) tests were negative. Hepatobiliary infections, celiac disease, Wilson’s disease, and alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency were excluded as well. We aimed to exclude potential factors influencing the level of hematological parameters evaluated in our survey. None of the persons included to the study was on steroid therapy.

Procedures

Venous blood samples (peripheral blood) were collected from the studied patients and controls (S-Monovette, SARSTEDT, Aktiengesellschaft and Co., Nubrecht, Germany). Ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid was used to obtain hematological parameters andcitrate to assess clotting indices. Biochemical markers were measured from the remaining blood sample without anticoagulant. The blood was obtained after at least 12 h of fasting. Hematological and biochemical parameters were obtained 4 h after blood samples collection. All the tests were performed in the laboratory of Clinical Hospital Number 4, Lublin, Poland. The analysis of morphotic blood indices was done with automatic ADVIA 2120i analyzer, Siemens and biochemical markers with ADVIA 1800 analyzer, Siemens. Prothrombin time (PT) and its International Normalized Ratio (INR) were measured with ACL TOP 500 analyzer, Instrumentation Laboratory. The part of blood samples without an anticoagulant was centrifuged at speed 2000 g for 10 min within 15 min from blood collection. Obtained serum was stored in 1 mL Eppendorf test tubes in the temperature of -80° Celsius until the measurement of direct markers of liver fibrosis with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Among morphotic parameters of the blood NLR, PLR and MPR were obtained. The assessment of indirect indices of liver fibrosis included: AAR — AST (aspartate transaminase)/ALT (alkaline transaminase) (AST to ALT Ratio), APRI — [(AST/*ULN)/PLT × (109/L)] × 100; *ULN — upper limit of normal (AST to PLT Ratio Index), FIB-4 — [age × AST/PLT × (109/L)] × ALT1/2 (fibrosis-4), GPR — [GGT (γglutamyl transpeptidase)/ULN/PLT × (109/L)] × 100 (GGT to PLT Ratio). Model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score was used in ALC patients and NAFLD fibrosis score and BARD score were used in NAFLD group: MELD - 3.8 [*Ln bilirubin (mg/dL)] + 11.2 [Ln INR] + 9.6 [Ln creatinine (mg/dL)] + 6.4. *Ln — natural logarithm, NAFLD fibrosis score - (-1.675) + 0.037 × age (years) + 0.094 × BMI (body mass index) (kg/m2) + 1.13 × impaired fasting glucose/diabetes (YES — 1 point, NO — 0 points) + 0.99 × AST/ALT - 0.013 × PLT (× 109/L) - 0.66 × albumin (mg/dL), BARD score — AST/ALT ≥ 0.8, 2 points, BMI ≥ 28, 1 point; IFG/diabetes, 1 point; together 0-4 points. Among direct indices of liver fibrosis, procollagen I carboxyterminal propeptide (PICP), procollagen III aminoterminal propeptide (PIIINP), platelet-derived growth factor AB (PDGF-AB), transforming growth factor-α (TGF-α) and laminin were obtained. Laboratory test were done in the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Medical University of Lublin according to the manufacturer's instructions. The measurement of PICP and PIIINP was performed with quantitative ELISA tests (Wuhan EIAab Science, Wuhan China). The measurement of PDGF-AB and TGFα was done with R&D Systems Quantikine ELISA Kits (Minneapolis, MN, United States). Finally, the measurement of laminin was performed with Takara Laminin EIA Kit without Sulphuric Acid (Kusatsu, Shiga, Japonia).

Table 1 Clinical characteristics of study participants

Statistical analyses

Statistical analysis of the results was conducted using Statistica 13.0 (StatSoft Polska Sp. z o.o., Kraków, Poland) for Windows system. The demographic data and results of laboratory tests were presented as the mean value ± standard deviation and Student’s t test was used to compare these results. Deviation from normality was evaluated by Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Data were expressed as the median and range (minimum- maximum). The Mann-Whitney U test was used for between-group comparisons because of non-normal distribution. Spearman correlation analyses were used to verify the correlations. All probability values were two-tailed, and a value of P less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and area under the curve (AUC) values were applied to assess the sensitivity and specificity of examined markers and to evaluate proposed cut-offs of measured indices in the course of ALC and NAFLD.

RESULTS

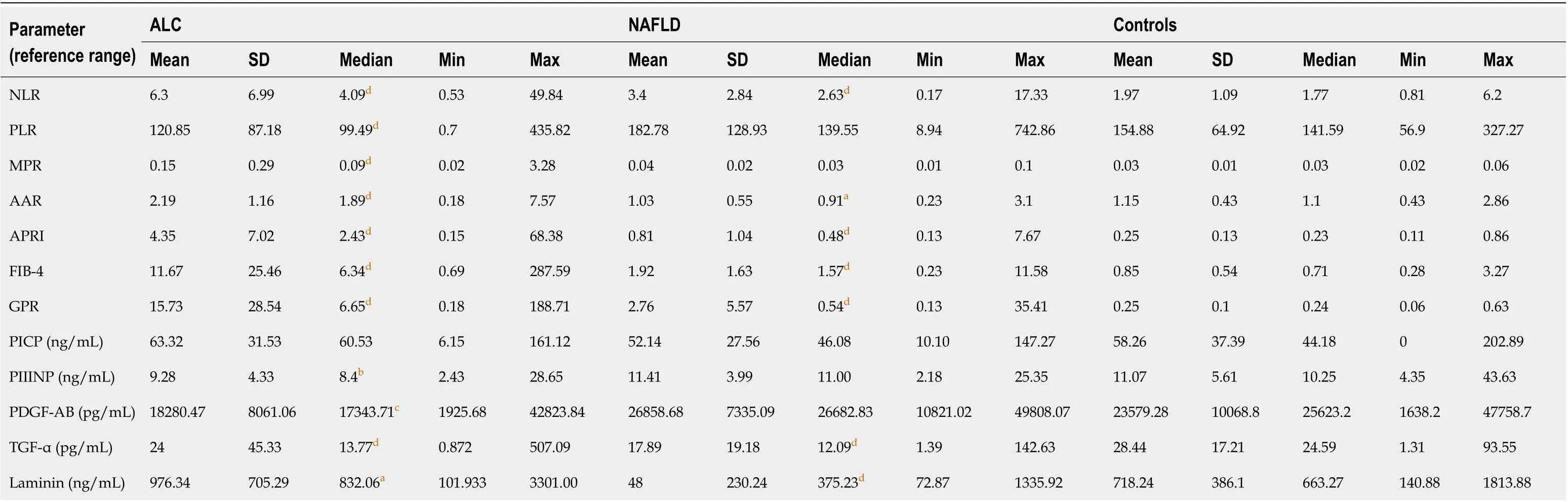

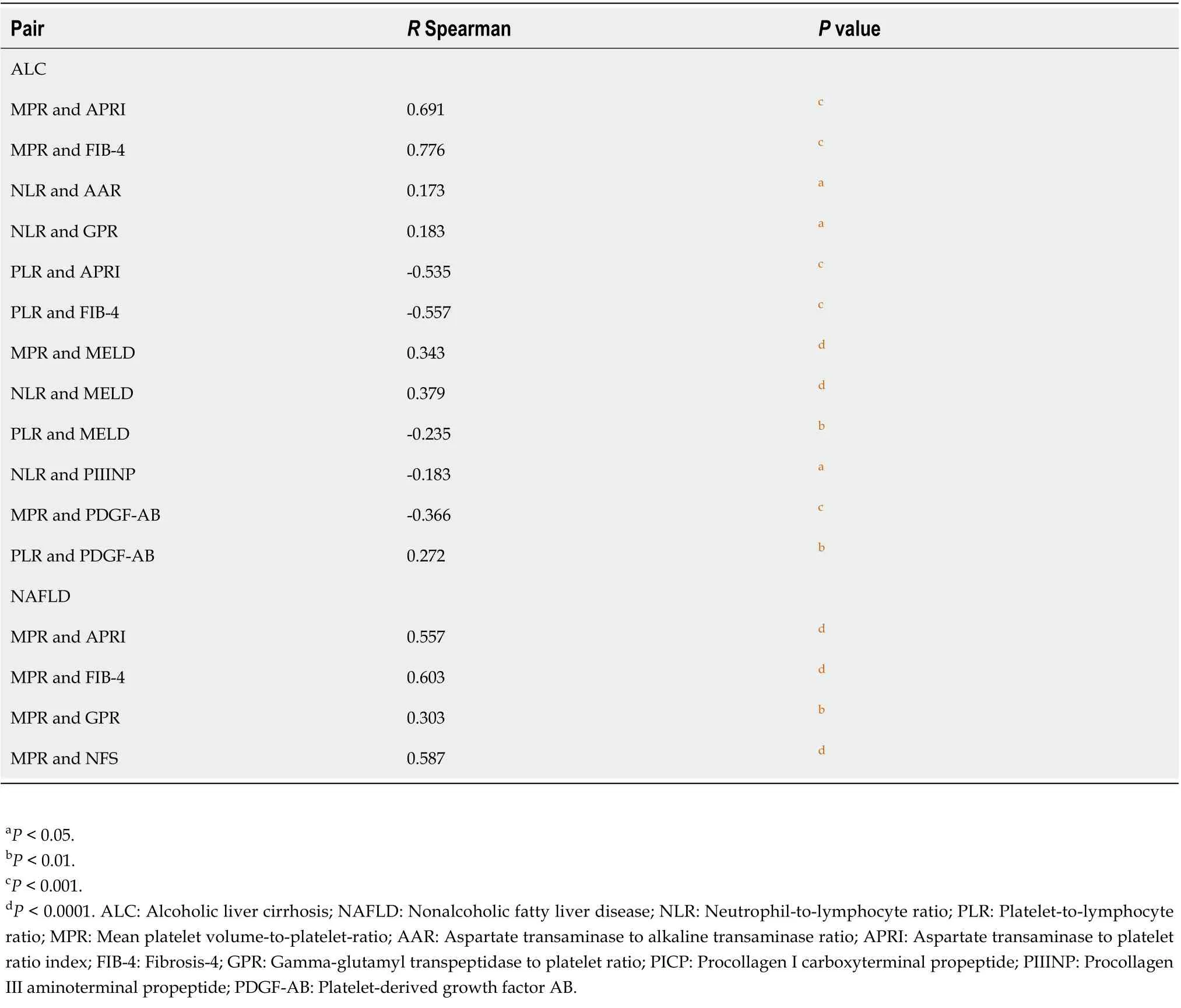

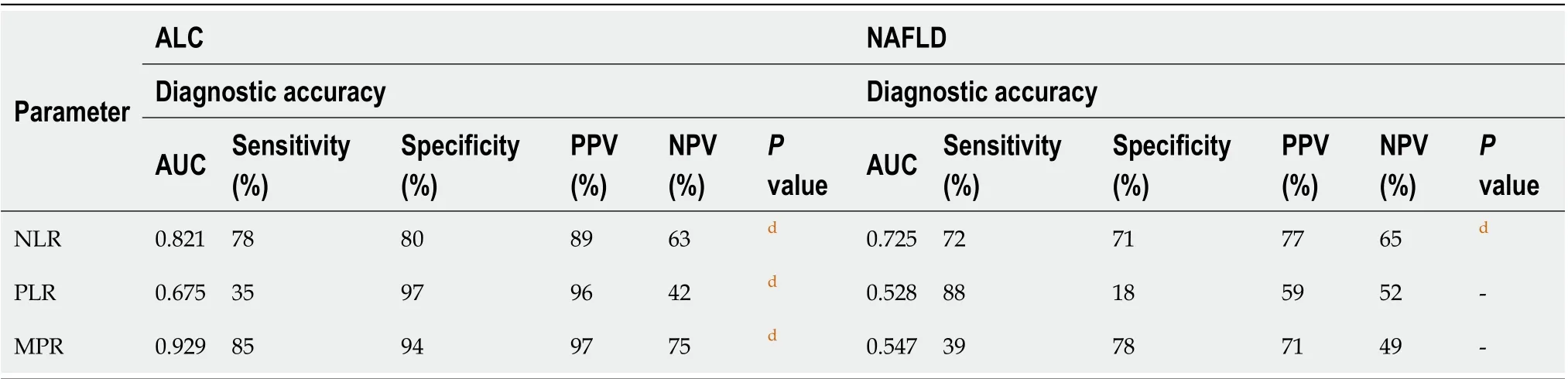

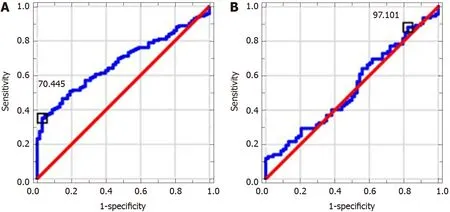

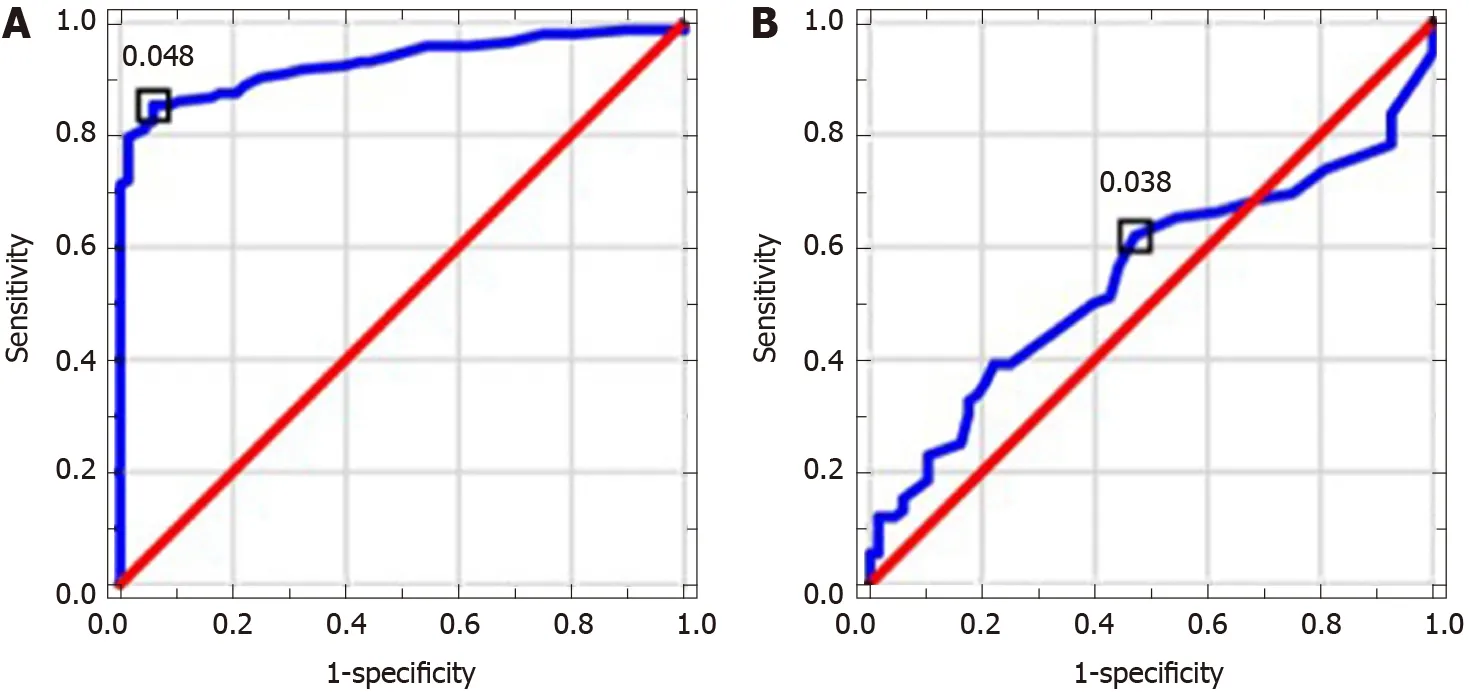

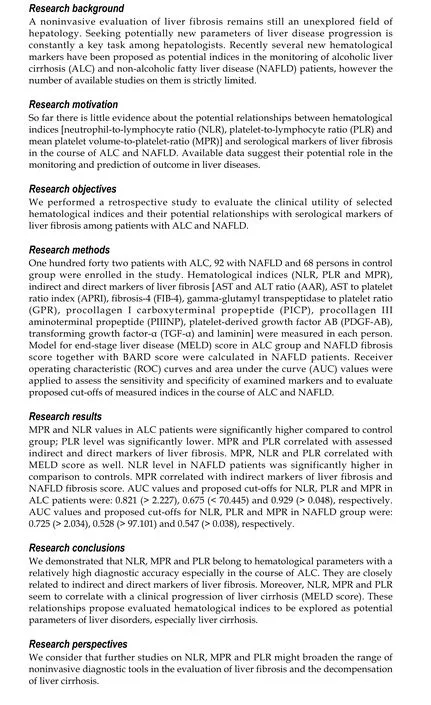

Table 2 shows results of used scores in research group. Table 3 presents results of hematological indices and serological (indirect and direct) markers of liver fibrosis in examined patients. MPR and NLR medians in ALC groups were significantly higher in comparison to controls (P < 0.0001); PLR level was significantly lower (P < 0.0001). NLR level in NAFLD patients was significantly higher compared to control group (P < 0.0001). MPR and PLR values did not differ significantly. The analysis of AAR, APRI, FIB-4 and GPR revealed their significantly higher medians in ALC patients compared to controls (P < 0.0001). Except for AAR, patients with NAFLD were found to have significantly higher values of all above-mentioned indices in comparison to controls (P < 0.0001). Among direct markers of liver fibrosis, laminin median in ALC group was significantly higher than in controls (P < 0.05). Beside of PICP, medians of PIIINP, PDGF-AB and TGF-α were significantly lower (P < 0.01, P < 0.001, P < 0.0001, respectively). Medians of TGF-α and laminin in NAFLD patients compared to controls turned out to be significantly lower (P < 0.0001). PICP, PIIINP and PDGF-AB medians did not differ significantly. Table 4 shows observed correlations between assessed markers in ALC and NAFLD patients. MPR and PLR correlated positively with indirect markers of liver fibrosis (APRI, FIB-4; P < 0.001) in examined ALC patients. Positive (but weaker) relationships were found between NLR and both: AAR and GPR (P < 0.05). PLR correlated positively with PDGF-AB and MPR-negatively (P < 0.001 and P < 0.01, respectively); a negative relationship was observed between NLR and PIIINP (P < 0.05). MELD score correlated positively with both: NLR and MPR (P < 0.0001) and negatively with PLR (P < 0.001). MPR correlated positively with indirect markers of liver fibrosis—APRI (P < 0.0001), FIB-4 (P < 0.0001) and GPR (P < 0.01) in NAFLD group. A strong positive relationship between MPR and NAFLD fibrosis score was noted, too (P < 0.0001). Diagnostic accuracy of examined hematological indices is shown in Table 5. ROCs presenting examined parameters in ALC and NAFLD patients are presented below in Figures 1-3. AUC values and proposed cut-offs for NLR, PLR and MPR in ALC patients were: 0.821 (> 2.227), 0.675 (< 70.445) and 0.929 (> 0.048), respectively. AUC values and proposed cut-offs for NLR, PLR and MPR in NAFLD patients were: 0.725 (> 2.034), 0.528 (< 97.101) and 0.547 (> 0.038), respectively.

以前的涉河项目主要是水利行业的涉河建设项目,随着经济社会的不断发展,非水利行业的涉河建设项目越来越多,包括码头建设、桥梁建设、线缆敷设等。日益增多的非水涉河项目,要求河道管理人员必须顺应社会发展的需要,加强非水涉河建设项目管理,保证涉河建设项目满足河道管理的法律法规要求。

DISCUSSION

Monitoring of liver fibrosis and clinical decompensation of liver failure with reliable and simple noninvasive markers obtained from the blood are two of the most essential research pathways in hepatology. On the other hand, the detection and careful monitoring of liver steatosis is also of great importance because of a significant prevalence of NAFLD all over the world and its possible severe complications. Looking for meaningful dependences between hematological parameters and the phenomenon of liver disorders has been intriguing scientists for several years. Despite their proved involvement in the course of liver fibrosis, there is still no clear answer whether to include them into the panel of diagnostic tests assessing cirrhotic patients. There were numerous attempts to evaluate a potential role of NLR in this area. Its increased level is explained to be the result of the release of interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor α together with coexisting bacterial translocation, followed by elevated NEUs count. Simultaneously, activated immune cells releasing cytokines and reactive oxygen species may inhibit lymphocytic immune response[10]. Of note, high level of NLR has been already proposed in several observations as a predictor of mortality in cirrhotic patients (independently from MELD score)[11-20]. Recently, Abu Omar et al[21]found NLR to be the marker of poor survival in alcoholic hepatitis patients, too. A coexisting inflammatory process (independent from liver cirrhosis) is an essential limitation connected with the utility of NLR and influencing its reliability. Thus, we excluded from our study all the participants suspected of the inflammation. NLR in studied ALC and NAFLD groups was characterized by quite high diagnostic accuracy (AUC = 0.821 and AUC = 0.725, respectively). It correlated significantly with MELD score and serological (AAR, GPR, PIIINP) markers of liver fibrosis in ALC patients. The role of NLR in the course of NAFLD remains ambiguous, however there are evidences suggesting that an increase in NLR might accompany the transformation from simple steatosis to steatohepatitis, highlighting the role of inflammatory processin the elevation of NLR[22,23]. PLR seems to be mostly explored among chronic HBV/HCV patients — recent investigations were performed by Lu et al[24]and Alsebaey et al[25]. Lower values of this parameter accompanied more advanced liver fibrosis, but the number of existing surveys is definitely small. On the other hand, high levels of PLR (together with NLR) were noted in patients with more advanced HCC and greater recurrence risk; similar observations concerned patients with pancreatic cancer and cholangiocarcinoma[26-29]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study figuring out the role of PLR in ALC and NAFLD population. PLR had relatively moderate diagnostic value in the research group, but it was significantly lower compared to controls and correlated with MELD score and both APRI and FIB-4 in ALC patients. It was carried out in former studies that higher levels of MPR correspond with histopathologically diagnosed liver cirrhosis; however available data on this issue are strictly limited and do not concern ALC and NAFLD patients. Cho et al[30]even found MPR as a potential marker of the development of HCC. In our studied ALC patients MPR obtained high diagnostic accuracy (AUC = 0.928); a cut-off value of 0.048 had a sensitivity of 85% and a specificity of 94%. It also correlated significantly with MELD score, serum concentration of PDGF-AB, APRI and FIB-4. According to available literature, it seems to be the first report concerning dependences between PLR and serological markers of liver fibrosis. In NAFLD group PLR level did not differ significantly from controls.

Table 2 Results of used scores in research group

The goal of our survey was not to compare a diagnostic accuracy of selected hematological indices between ALC and NAFLD patients. We tried to figure out whether an isolated liver steatosis might be affected by certain deviations in hematological indices. Our survey evaluated the population of patients with NAFLD without the assessment of coexisting hepatitis in liver biopsy. A general division of the research group into only two subgroups (ALC and NAFLD) can be perceived as a limitation, however it was the beginning of our exploration in this field of hepatology and our further direction will be the evaluation of the markers presented in this study among patients with different stages of ALC and NAFLD, including simple steatosis and steatohepatitis. A clinical stage of ALC was evaluated with MELD score and we did not find any significant differences according to the severity of the disease. The idea of the current study was caused by our clinical practice and a common presence of hematological parameters disturbances in the patients with liver disorder, especially ALC and NAFLD. These pathologies have an unquestionable global impact and there is still a great demand on finding new markers in their monitoring. PLR and MPR have been poorly explored in ALC and NAFLD patients, so far and the current study fills this important gap. Hematological markers are inseparably connected with serological markers of liver fibrosis in ALC and NAFLD patients. MPR and NLR turned out to be the most powerful markers in ALC patients.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, we demonstrated that NLR, MPR and PLR belong to hematological parameters with a relatively high diagnostic accuracy especially in the course of ALC. They are closely related to indirect and direct markers of liver fibrosis. Moreover, NLR, MPR and PLR seem to correlate with a clinical progression of liver cirrhosis (MELD score). These relationships propose evaluated hematological indices to be explored as potential parameters of liver disorders, especially liver cirrhosis.dP < 0.0001. ALC: Alcoholic liver cirrhosis; NAFLD: Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; AUC: Area under the curve; PPV: Positive predictive value; NPV: Negative predictive value.

Table 3 Results of hematological indices and serological (indirect and indirect) markers of liver fibrosis in examined patients

Table 4 Correlations between examined parameters in examined alcoholic liver cirrhosis and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease patients

Table 5 Diagnostic accuracy of hematological indices in examined alcoholic liver cirrhosis and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease patients

Figure 1 Receiver operating characteristics for neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in alcoholic liver cirrhosis and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease groups. Area under the curve value (AUC) = 0.821 (cut-off > 2.227) and AUC = 0.725 (cut-off > 2.034), respectively. A: Alcoholic liver cirrhosis; B: Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.

Figure 2 Receiver operating characteristics for platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio in alcoholic liver cirrhosis and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease groups. Area under the curve value (AUC) = 0.675 (cut off < 70.445) and AUC = 0.528 (cut-off < 97.101), respectively. A: Alcoholic liver cirrhosis; B: Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.

Figure 3 Receiver operating characteristics for mean platelet volume-to-platelet-ratio in alcoholic liver cirrhosis (A) and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (B) groups. Area under the curve value (AUC) = 0.929 (cut-off > 0.048) and AUC = 0.547 (cut-off > 0.038), respectively. A: Alcoholic liver cirrhosis; B: Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

World Journal of Gastroenterology2020年47期

World Journal of Gastroenterology2020年47期

- World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Clinical features of multiple gastrointestinal stromal tumors: A pooling analysis combined with evidence and gap map

- Multiple cerebral lesions in a patient with refractory celiac disease: A case report

- Therapeutic efficiency of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells for liver fibrosis: A systematic review of in vivo studies

- Blockage of ETS homologous factor inhibits the proliferation and invasion of gastric cancer cells through the c-Met pathway

- Extracellular histones stimulate collagen expression in vitro and promote liver fibrogenesis in a mouse model via the TLR4-MyD88 signaling pathway

- Prevalence and associated factors of obesity in inflammatory bowel disease: A case-control study