A Study of Feminine Space in Romance of the Three Kingdoms

You Cuiping

Sichuan Academy of Social Sciences

Abstract: Space plays a critical role in Romance of the Three Kingdoms. This paper examines the construction of feminine space in the fiction by applying the theory of gendered space and using methods such as induction, comparison, and mutual corroboration of literature and history. The feminine space in the fiction was constructed on the basis of “gender segregation.” The female characters mainly stayed at the “backyard” of homesteads, and were rarely seen in external spaces, leaving space power in the hands of men. However, thanks to certain special opportunities, status, or class, women could acquire some knowledge and abilities not available to them in the space. Under such circumstances, they had the chance to reverse the space power. The fiction presents the richness and complexity of feminine space and circumstances in the late Han Dynasty.

Keywords: feminine space, gender segregation, narrative pattern, reversal of power

From the perspective of spatial criticism,Romance of the Three Kingdomsis a historical fiction with a great sense of space. This fiction provides a vivid depiction of the constant battles for geographical space between different military groups, large and small, for much of a century from warlords’ contention for hegemony in the late Eastern Han Dynasty (25-220 AD), through the tripartite confrontation of the three kingdoms of Wei, Shu, and Wu, to the eventual unification of China by Jin Dynasty (265-420 AD). Changes in space often indicate changes in social relations and status and even changes in power structures.Romance of the Three Kingdomspresents real and concrete geographical spaces in which political conflicts, power struggles, and turnovers staged in turn, and in which various social relations were developed and reconstructed. From the perspective of feminist geography, space is not a neutral or objective existence but is gendered. “Spaces and places are not only themselves gendered but, in their being so, they both reflect and affect the ways in which gender is constructed and understood” (Massey, 2018, pp. 231-232). This paper applies the theory of gendered space to examine the construction of feminine space inRomance of the Three Kingdoms, and thereby explore its narrative pattern and reversal of space power in spatial movement.

Feminine Space in the Context of “Gender Segregation”

The author’s political stance is shown right from the very beginning of the fiction. In the opening chapter, there were mentions of various evil omens and geological disasters in the late Han (206 BC-220 AD). Evil omens included the appearance of a monstrous black serpent that coiled itself on the very seat of majesty, certain hens’ suddenly crowing like roosters, a long wreath of murky clouds winding their way into the Hall of Virtue, and a rainbow seen in the Dragon Chamber. Geological disasters ranged from a terrific hailstorm, an earthquake (in Luoyang), and a huge tidal wave (tsunami) along the coast, to the collapse of part of the Five Mountains. Emperor Ling of Han thus issued an edict asking his ministers for an explanation of such calamities and omens. Cai Yong, a court counselor, replied that all these were brought about by the “interference of the imperial harem (empresses, concubines and/or imperial maternal relatives) and eunuchs in state affairs.” The minister’s memorial was not accepted, “so the corrupt state administration went quickly from bad to worse, till the country was ripe for rebellion and buzzed with brigandage” (Luo, 2019, p. 2). It was precisely against such a backdrop that constant battles for geographical space were launched between/among rebels, bandits, heads of vassal states, and ambitious militants in the late Han. The author’s political stance against the “interference of the imperial harem and eunuchs in state affairs” was also reflected in his construction of feminine space in the fiction.

Being a men’s epic,Romance of the Three Kingdomsfeatured only 80 or so female characters, too few when compared with thousands of male characters. By class, its female characters could be divided into the upper, middle, and lower classes, with the middle and upper classes being the majority. By appearance and temperament, they could be identified as beauties, talented women, eminent women, loving mothers, virtuous wives, and jealous women. In the fiction, men moved freely in a diversity of spaces such as open country, cities, battlefields, local authorities,yamen(government organs), and temples; by contrast, women, regardless of their family background (the royalty, the nobility, the military, or the populace), were largely restricted to relatively small, enclosed spaces inside their residence, such as the imperial harem, the inner chamber, the backyard, and the private garden. And there is no shortage of such descriptions. Below are some excerpts:

Empress (Dowager) He… prepared a banquet (in the palace) to which she invited her rival Empress (Dowager) Dong.

When Sun Quan arrived (at the inner chamber), he found his mother (Dowager Marchioness) beating her breast and weeping bitterly.

On the way, he (Yang Fu) went to (the inner courtyard of) his maternal cousin, General Jiang Xu… The general’s mother… was Yang Fu’s aunt. When Yang Fu saw her, he wept before her.

And Xin Chang went into the inner chamber … There, he met his (elder) sister, Xin Xianying, who asked the meaning of all this haste (Luo, 2019, pp.19, 462, 552, 925).

Diao Chan, who was a singing girl, spent her life mainly in the private garden and private apartments inside Wang Yun’s residence. Below is an excerpt:

He (Wang Yun) took his staff and went strolling in his private garden… Suddenly he heard a rustle in the Peony Pavilion and someone sighing deeply. Stealthily creeping near, he saw there one of the household singing girls named Diao Chan.… When Lü Bu arrived, he was met at the gate by Wang Yun himself and within found a table full of dainties for his delectation. He (Lü Bu) was conducted into the private apartments and placed in the seat of honor… Soon appeared two attendants, dressed in white, leading between them the exquisite and fascinating Diao Chan… When it grew late and the wine had done its work, Dong Zhuo was invited to the inner chamber… Then a curtain was lowered. The shrill tones of reed instruments rang through the room, and presently some attendants led forward Diao Chan, who then danced on the outside of the curtain (Luo, 2019, pp. 66-67).

Regarding Cao Pi’s first encounter with his wife and also his war trophy Lady Zhen, a stunning beauty, it happened “in a room” of “Yuan Shao’s residence” according toA Brief [History] of Wei (Wei Lüe).①As recorded in A Brief History of Wei (Wei Lüe), “Yuan Xi left to assume his appointment as regional inspector of Youzhou (You Prefecture). Lady Zhen did not follow her husband (Yuan Xi) and remained in the City of Ye, the administrative center of Yuan Shao’s domain, to take care of her mother-in-law. After the fall of the City of Ye, Cao Pi (later known as Emperor Wen of Wei) entered Yuan Shao’s residence and met Lady Liu (Yuan Shao’s widow) and Lady Zhen in a room” (Chen, 2009, p. 54).But their first encounter was set in the “private rooms” in the fiction. “Sword in hand… he made his way into the private rooms, where he saw two women weeping in each other’s arms” (Luo, 2019, p. 288).

The construction of feminine space inRomance of the Three Kingdomsshows the spatial dimension of the author’s gender view and presents the Confucian ideal that “distinction should be observed between man and woman.” Its division of gendered spaces echoes the secular principle of “a man responsible for external affairs and a woman in charge of domestic affairs.” The heterosexual avoidance (similar to “gender segregation”) was a long-lasting system in ancient China. This system was introduced loosely prior to the Sui Dynasty (581-618 AD) and Tang Dynasty (618-906 AD) and was established during the Sui and Tang. Since then, its implementation has become increasingly strict. According to the heterosexual avoidance, unmarried women were only allowed to enter the inner chamber and the side inner chamber for reading, reviewing lessons, or “inquiring after parents’ welfare” (a daily practice of filial piety); married women lived with their husbands in wing rooms on either side of the compound, which means they could move in a bigger area but were still confined behind the “harem gate.” Regarding the “distinction between man and woman,” there were clear rules in the “Pattern of the Family” (“Nei Ze”),Book of Rites(Liji):

The observances of propriety commence with careful attention to the relations between husband and wife. They built the mansion and its apartments, distinguishing between the exterior and interior parts. The men occupied the exterior, the women the interior. The mansion was deep, and the doors were strong, guarded by porter and eunuch. The men did not enter the interior; the women did not come out into the exterior. (Ruan, 1997, p. 1468)

The men should not speak of what belongs to the inside (of the house), nor the women of what belongs to the outside. Except at sacrifices and funeral rites, they should not hand vessels to one another. In all other cases, when they have occasion to give and receive anything, the woman should receive it in a basket. If she has no basket, they should both sit down, and the other put the thing on the ground, and she then takes it up. Outside or inside, they should not go to the same well, nor to, the same bathing-house. They should not share the same mat in lying down; they should not ask or borrow anything from one another; they should not wear similar upper or lower garments. Things spoken inside should not go out. Words spoken outside should not come in. (Ruan, 1997, p. 1462)

It can be inferred from the fiction that the author (Luo Guanzhong) was in favor of this spatial ritual system. Significantly, the fiction is believed to have been created in the late Yuan (1271-1368 AD) and early Ming (1368-1644 AD) dynasties. Accordingly, all spatial arrangements and imaginations of the author inevitably bear the mark of his era, and partly deviate from the social reality of the late Han Dynasty and the Three Kingdoms period. One example is “eavesdropping behind the screen,” which occurred on several occasions. In the fiction, Lady Cai used to eavesdrop behind the screen while her husband Liu Biao was talking with his guest; Lady Zhurong’s laugh came from behind the screen before she appeared. Such depictions imply that the screens were quite tall, and that they were used to bestow a sense of privacy. The relevant historical records, however, show quite a different picture:

From the Warring States period to the Three Kingdoms period, people were used to sitting on the floor, and therefore tables, desks, clothes hangers, and beds were all much shorter than later… A bed was for receiving guests, as well as for sleeping. But such a bed was smaller and was also known as “a couch” (ta). Usually, one couch was for only one person. There was also a type of big bed occupying most of the indoor space, with a small table placed on its surface, and a screen around it. (Liu, 1980, p. 52)

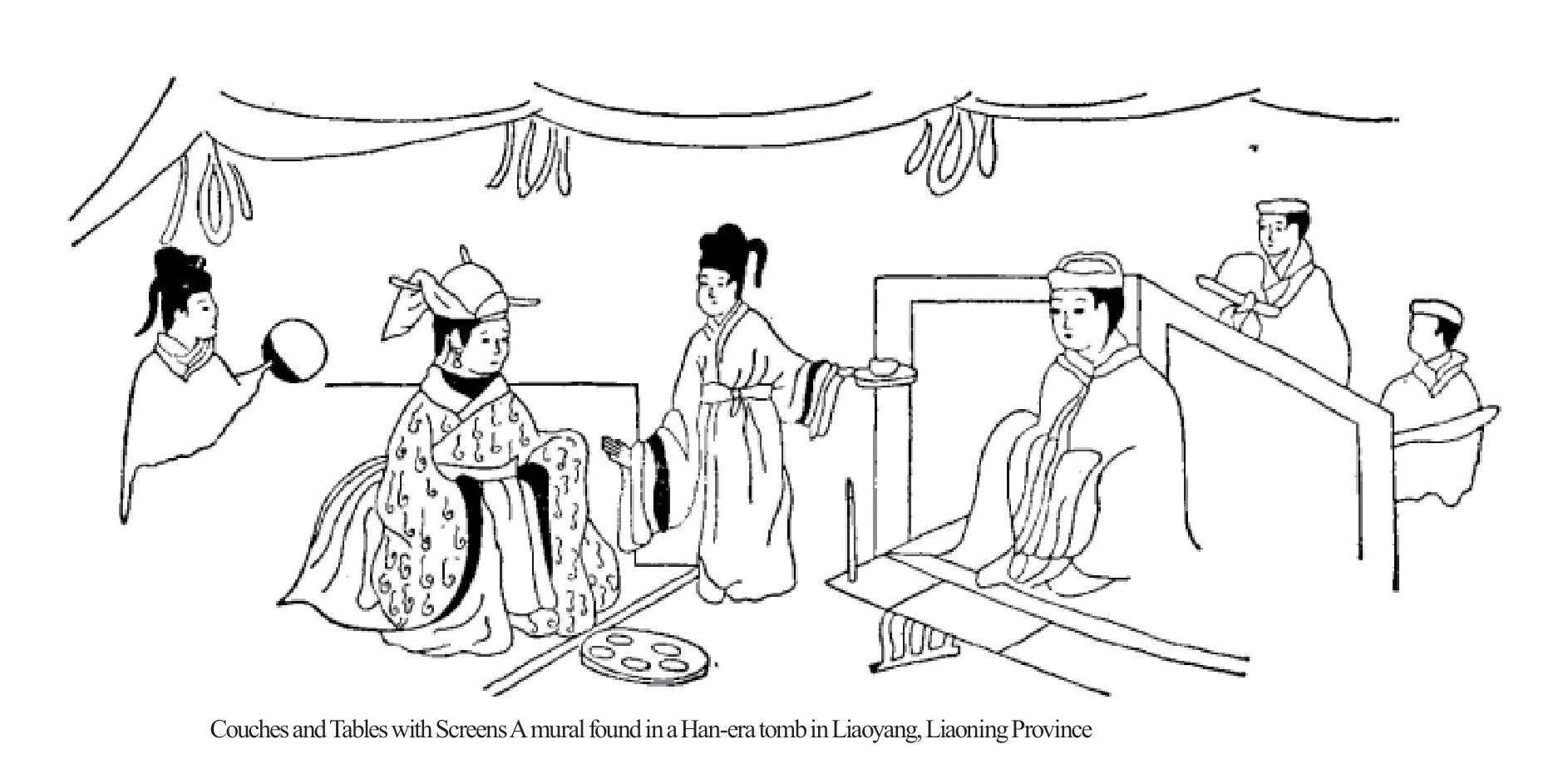

Figure 1. Couches and Tables with Screens in the Han Dynasty (Liu, 1980, p. 52)

Given that the screen should match the low bed, it was unlikely to also serve as a separating wall for eavesdroppers.

In fact, the author did not seem to pay much attention to detailing or distinguishing the domestic spaces where relevant characters appeared, but often used the umbrella terms “private room,” or “inner chamber” to refer to them. Still, there were exceptions in some chapters giving vivid descriptions of some characters’ spatial movements, which are exactly the focus of this analysis. It is through these spatial movements that we can catch a glimpse of the logic and power relations behind the author’s construction of gendered spaces.

It can be seen from the fiction that “observing the distinction between man and woman” was part of traditional etiquette and also a demonstration of “male superiority and female inferiority,” a traditional power relation. After all, according to Massey:

All attempts to institute horizons, to establish boundaries, to secure the identity of places, can in this sense, therefore, be seen to be attempts to stabilize the meaning of particular envelopes of space-time. They are attempts to get to grips with the unutterable mobility and contingency of space-time… For such attempts at the stabilization of meaning are constantly the site of social contests, battles over the power to label space-time, to impose the meanings to be attributed to a space, for however long or short a span of time. (Massey, 2018, p. 9)

A male master (head of a family) usually held space power within his residence. He was free from any space constraints there, but other men did not enjoy such freedom. Take the homestead of Wang Yun as an example. To implement his chaining scheme to divide Dong Zhuo and Lü Bu, Wang Yun, who was the male master of his homestead, gave banquets at will in both the lobby and the inner chamber, as opposed to Diao Chan, whose presence was mostly restricted to the private garden and the inner chamber. Another example is the residence of Zhuge Liang. During Liu Bei’s three visits to Zhuge Liang’s cottage, he was invariably received by Zhuge Liang and his younger brother, along with some boy servants, but did not meet any of the family’s womenfolk.

A male master’s failure to hold space power could lead to the transfer of power to a woman, or an outsider, or result in invalid spatial “gender segregation,” which could give rise to going beyond the space authority and crossing the line between gendered spaces, and subsequently bring about great troubles. In this regard, a prime example is Lady Cai, wife of Liu Biao. Driven by ambition, Lady Cai frequently interfered in her husband’s business, and was eager to make her own son the heir. “Lady Cai had a suspicion why her lord (husband) had summoned Liu Bei and what was the subject of discussion, so she had determined to listen secretly” (Luo, 2019). Once, Liu Bei said to Liu Biao, “All experience proves that to set aside the elder for the younger is to take the way of confusion” (Luo, 2019). This talk was overheard by Lady Cai, who also did not think Liu Bei to be someone willing to remain long in a lowly position. So, she tried to persuade Liu Biao to “remove” Liu Bei at the earliest opportunity, but Liu Biao refused. She then gathered her men to kill Liu Bei. There were multiple occasions when Liu Biao drank with his guest Liu Bei in the inner chamber, with Lady Cai always eavesdropping behind the screen. After that, she would advise her husband accordingly, and even take action without her husband’s permission. Lady Cai’s “eavesdropping behind the screen” was an attempt to cross the line between gendered spaces and to go beyond her authority. In practice, she violated the secular principles of “man responsible for external affairs and woman in charge of domestic affairs” and of “women should not speak of what belongs to the outside.” When the violation of these secular principles happened in the royal family, the consequences would be even more serious. For example, after the death of Emperor Ling of Han, Empress Dowager Dong and Empress Dowager He competed for power, leading to the poisoning of Empress Dowager Dong by He Jin, elder brother of Empress Dowager He, and the subsequent killing of Empress Dowager He and Emperor Shao of Han (Liu Bian) by Dong Zhuo. In the fiction Dong Zhuo replaced Emperor Shao of Han with Emperor Xian of Han (Liu Xie), and then committed regicide (by having Liu Bian killed). During this process, the division of gendered spaces in the palace was destroyed, and neither Emperor Shao of Han nor Empress Dowager could control the imperial space power at all. Below is an excerpt:

After this the late Emperor now Prince of Hongnong, his mother, and the Imperial Consort, Lady Tang, were removed to the Palace of Forever Calm (by Dong Zhuo). The entrance gates were locked against all comers… Li Ru was sent with ten men into the palace to consummate the deed. The three were in one of the upper rooms when Li Ru arrived… Thereupon Li Ru grew angrier, laid hands on the Empress (Dowager) and threw her out of the window. Then he bade the soldiers strangled Lady Tang and forced the lad to swallow the wine of death. Li Ru reported the achievement to his master who bade them bury the victims without the city. After this Dong Zhuo’s behavior was more atrocious than before. He spent his nights in the Palace, defiled the imperial concubines there, and even slept on the Dragon Couch. (Luo, 2019, pp. 32-34)

The Imperial Palace of the Eastern Han Dynasty, which was located in Luoyang, consisted of the North Palace and the South Palace. Inside the North Palace, two sub-palaces, namely, the Palace of Eternal Happiness (Yongle Gong) and the Palace of Forever Calm (Yongan Gong), were private residences of the emperor and his empress and concubines. Both the North Palace and the South Palace were used for court hearings and audiences, with the grand assembly on New Year’s Day held in the Hall of Virtuous Light (Deyang Dian) in the North Palace (Yang, 2016, p.135). The dethroned Emperor Shao of Han, his mother and the Imperial Consort, Lady Tang were under house arrest in the Palace of Forever Calm, whereas Dong Zhuo and his warriors had free access to the Imperial Palace. This unrestricted cross-space movement of the Dong faction indicated the deprivation of imperial power from the House of Liu.

In addition, the author’s judgment of male characters is also reflected in whether they went beyond the space authority and crossed the line between gendered spaces. And this can be highlighted by a comparison of Lü Bu and Guan Yu regarding “gender segregation.” Lü Bu, who was a foster son of Dong Zhuo, went in and out of Dong’s residence freely, taking every opportunity to exchange flirting glances with Diao Chan. Below is an excerpt:

Lü Bu… made his way into the private quarters… Next he crept round behind his master’s sleeping apartment. By this time, Diao Chan had risen and was dressing her hair at the window. Looking out she saw a long shadow fall across the little lake. She recognized the headdress and peeping around she saw it was indeed no other than Lü Bu. Thereupon she contracted her eyebrows, simulating the deepest grief, and with her dainty handkerchief she wiped her eyes again and again. Lü Bu stood watching her a long time. Soon after he went in to give morning greeting. Dong Zhuo was sitting in the reception room… Lü Bu waited while Dong Zhuo took his morning meal. As he stood beside his master, he glanced over at the curtain and saw a woman there behind the screen showing a half face from time to time and throwing amorous glances at him… One day Lü Bu went to inquire after his father’s health. Dong Zhuo was asleep, and Diao Chan was sitting at the head of his couch. Leaning forward she gazed at the visitor, with one hand pointed to her heart, the other at Dong Zhuo asleep, and her tears fell. Lü Bu felt heartbroken. (Luo, 2019, p. 69)

There was a mention of how Lü Bu crossed the line between gendered spaces in the “Biography of Lü Bu,” theRecords of the Three Kingdoms:

Dong Zhuo often had Lü Bu guard the small door of the inner chamber, allowing Lü Bu the opportunity to fornicate with Dong Zhuo’s maids. Because of that, Lü Bu could not live in peace, constantly frightened that his scandal would come to light. (Chen, 2009, p. 74)

Unlike Lü Bu, Guan Yu never attempted to cross the line between gendered spaces. There was a time when he was out of touch with Liu Bei and temporarily surrendered himself to Cao Cao. Still, he managed to protect his two sisters-in-law without crossing the line. Below is an excerpt:

For the journey to the capital, a carriage was prepared for the two ladies, and Guan Yu was its guard. On the road they rested at a certain post station, and Cao Cao, anxious to compromise Guan Yu by beguiling him into forgetfulness of his duty, assigned Guan Yu to the same apartment as his sisters-in-law. Guan Yu stood the whole night before the door with a lighted candle in his hand. Not once did he yield to fatigue. Cao Cao’s respect for him could not but increase. At the capital (Xuchang), the Prime Minister assigned a dignified residence to Guan Yu, which he immediately divided into two enclosures, the inner one for the two ladies and the other for himself. He placed a guard of ten of his veterans over the women’s quarters… In fact, from the day of arrival in the capital, Guan Yu was treated with marked respect and distinction, small banquets following each other in every three days, and large banquets held in every five days. Cao Cao also presented him with ten most lovely serving girls; Guan Yu sent these also within to wait upon his two sisters-in-law. Every third day Guan Yu went to the door of the women’s quarters to inquire after their welfare, and then they asked if any news of the wanderer had come. This ceremony closed with the words: “Brother-in-law, you may retire when you wish.” (Luo, 2019, pp. 222-223)

Even in an emergency, Guan Yu still strictly observed the “distinction between man and woman” and the “order of superiority and inferiority,” never stepping into the inner courtyard. He just “set his dress in order, went over, and knelt by the door” to comfort his sisters-in-law and inquire after their welfare. In this way, he safeguarded the monarch-subject relationship and kept an appropriate distance from feminine space. Below is an excerpt:

One day when Guan Yu was at home, there came a messenger to say that the two women had thrown themselves on the ground and were weeping. They would not say why. Guan Yu set his dress in order, went over, and knelt by the door, saying, “Why this grief, Sisters-in-law?”… “Dreams are not to be credited,” he replied. “You dreamed of him because you were thinking of him. Pray do not grieve.” (Luo, 2019, pp. 222-223)

The feminine space inRomance of the Three Kingdomswas constructed based on “gender segregation.” The female characters mainly stayed in the “backyard” of homesteads. But this assumption was not so close to the social reality of the late Han Dynasty and the Three Kingdoms period, when women were not only engaged in indoor activities such as weaving and embroidery, but also in economic activities such as agricultural production, livestock feeding, winemaking and selling, handicraft manufacturing, as well as peddling. So, there was, in fact, plenty of room for women to give play to their abilities (Zhai, 2005a). Even for those concubines and maids in the imperial palace, lifelong seclusion in the harem was by no means their inevitable outcome. Instead, they had a variety of ways out, such as returning home from the palace after retirement, marrying someone by imperial order, following dukes to their vassal states, and guarding imperial mausoleums. Without much emphasis on chastity, the social environment of the Han Dynasty and the Three Kingdoms period was arguably friendly to women in imperial China (Zhai, 2005b). It is worth mentioning that Luo Guanzhong, the author ofRomance of the Three Kingdoms, lived during the late Yuan and early Ming dynasties, when Confucianism was the norm in Chinese culture. His work inevitably bears the mark of his era.

Narrative Pattern for Women’s Cross-Space Movement

In accordance with the Confucian ideal that “distinction should be observed between man and woman,” women were supposed to stay quietly in the “backyard” of homesteads as much as possible, spinning, weaving, embroidering, managing household affairs, as well as giving birth to and bringing up children. Still, it was impossible for women to avoid intra- and crossspace movement completely. Such intra- and cross-space movement was inevitable inside a homestead, and could also occur in a much larger world due to war and marriage. Female characters as a whole inRomance of the Three Kingdomsdid not have much presence in external spaces, where they could only be seen for reasons such as political change, strategic shifts, war, marriage and visits to parental homes. Examples include Lady Gan and Lady Mi, who moved around as a result of Liu Bei’s victories and defeats in war; Lady Sun, who traveled between Jingzhou and Eastern Wu (State of Wu); and daughter of Lü Bu, who was betrothed by his father to different men for political gains. On the women’s cross-space movement in the fiction, there is always a clear stance, which implies the moral judgment of the author.

Sometimes, such cross-space movement by women was to flee the war and was usually accompanied by miseries. For example, Liu Bei’s concubines, Lady Gan and Lady Mi were constantly on the move, suffering a lot from war. For multiple times, they (and the son) were left by Liu Bei during the war, with one captured and the other hunted down. Their movement between spaces was filled with hardship and misfortune, which can be exemplified by their experience at the Long Slope Bridge (Changbanpo). Below is an excerpt:

Then Zhao Yun rode off toward the Long Slope Bridge… “Not very long ago, I saw the Lady Gan go south with a party of other women. Her hair was down and she was barefooted.”… A woman in the rear of the party looked up at him and uttered a loud cry… Lady Gan replied, “She and I were forced to abandon our carriage and mingle with the crowd on foot. Then a band of soldiers came up and we were separated. I do not know where they are. I ran for my life.”… Zhao Yun rode to look and there, beside an old well behind the broken wall of a burned house, sat the mother clasping the child to her breast and weeping. Zhao Yun was on his knees before her in a moment. “My child will live then since you are here,” cried Lady Mi. “Pity him, O General; protect him, for he is the only son of his father’s flesh and blood. Take him to his father and I can die content.”… She said no more. Throwing the child on the ground, she turned over and threw herself into the old well. And there she perished. (Luo, 2019, pp. 360-362)

When Liu Bei was transferring the people of Fancheng in war, Lady Gan and Lady Mi were traveling in a carriage protected by soldiers. But later Liu Bei’s army was defeated, so they had no choice but to leave the equipment behind. Lady Gan went south “with a party of other women. Her hair was down and she was barefooted.” Lady Mi took the child Liu Shan with her. Badly wounded, she could not go any farther. She sat beside an old well behind the broken wall of a burned house, clasping the child to her breast and weeping. It was a tragic scene. Zhao Yun urged Lady Mi to take his horse, while he would walk beside and protect her and Liu Shan till they got clear. Not wishing to be a burden on their journey for survival, Lay Mi threw herself into an old well and died.

Sometimes, women’s cross-space movement was about marriage and visits to parental homes. This was the case with Lady Sun, a fierce-tempered and determined heroine who “preferred to face the (gun) powder rather than powder the face.” Her movement in external spaces was full of adventure, if not suffering. She traveled from Eastern Wu (State of Wu) to Jingzhou, and later returned from Jingzhou to Eastern Wu. Such a “round trip” was made in accordance with men’s will. She went to Jingzhou with Liu Bei because she believed that Jingzhou was in great danger, which turned out to be a lie told by Liu Bei’s men. Her company ensured Liu Bei a successful escape from Eastern Wu. Later, she returned to Eastern Wu because she received the news that her mother was critically ill, which, again, was a lie told by Sun Quan’s men. Besides, there were pursuing troops on both trips. On her way to Jingzhou with Liu Bei, they had to repulse the attack from Sun Quan’s troops, while on her return trip, her party was stopped by Zhao Yun and Zhang Fei with Shu-Han troops on the river.

Other times, women’s cross-space movement was due to their involvement in war. Among those women were Lady Zhurong and Lady Wang, wife of Zhao Ang. Lady Zhurong was the only female character in the fiction that had actual battlefield experience. She could fight on horseback and drink with men. She was free, bold, and unconstrained. Below are two excerpts:

A laugh came from behind the screen, and a woman appeared, saying, “Though you are brave, how stupid you are! I am only a woman, but I want to go out and fight.”… She was a descendant of the Zhurong family of the Southern Mang (Man). She was an expert in the use of the flying sword and never missed her aim… Lady Zhurong thereupon mounted a horse and forthwith marched out at the head of a hundred generals, leading fifty thousand troops of the ravines, and set out to drive off the troops of Shu. (Luo, 2019, p. 768)

The chief prisoners were Meng Huo, Lady Zhurong, Meng You, and Dai Lai. There were many of his clan as well. As they were eating and drinking, a messenger appeared in the door of the tent… (Luo, 2019, p. 775)

Lady Zhurong was similar to Lady Sun in the sense that they were both fierce-tempered women who had a taste for warlike things. Yet Lady Sun, who was a princess of the Eastern Wu, normally went out in a carriage rather than on horseback. By contrast, Lady Zhurong was a barbarian yet to be civilized in the eyes of the author, although she moved freely. Lady Wang was the wife of Zhao Ang. They had a son, Zhao Yue, who was an officer in the army of Ma Chao. When Zhao Ang had to consent to take part against Ma Chao, he became worried for the safety of his son. But Lady Wang encouraged her husband to share the expedition even at the expense of their son’s life. Below is an excerpt:

But his wife replied angrily, “Should anyone grudge even his life to avenge his liege lord or his father? How much less a son? My lord, if you let the thought of your son stay your hand, then will I die forthwith.”… The wife of Zhao Ang sold her ornaments and went in person to her husband’s camp to feast on his soldiers. (Luo, 2019, p. 553)

Such cross-space movement was essentially entrusted by male authorities or driven by a sense of loyalty and righteousness and was no more than an exceptional process that would not last long.

There is still one more type of women’s cross-space movement, which can only be grasped by reading between the lines due to the author’s deliberate equivocation. One example is the cross-space movement of Lady Zou, wife of Zhang Ji. Cao Cao was so trapped by the charm of Zou as to lose his beloved son, nephew and senior general. Below is an excerpt:

One day, when Cao Cao returned to his quarters in a more than usual merry mood, he asked the attendants if there were any singing girls in the city. His nephew, Cao Anmin, heard the question and said, “Peeping through one of the partitions last evening, I saw a perfectly beautiful woman in one of the courts. They told me she was the wife of Zhang Ji, Zhang Xiu’s uncle. She is very lovely.” Cao Cao, inflamed by the description given him of the beauty, told his nephew to go and bring her to visit him. Cao Anmin did so, supported by an armed escort (of 50 soldiers), and very soon the woman stood before Cao Cao. She was a beauty indeed, and Cao Cao asked her name. She replied, “Thy handmaid was wife to Zhang Ji, and I was born of the Zou family.” “Do you know who I am?” “I have known the Prime Minister by reputation a long time. I am happy to see him and be permitted to bow before him,” said she. “It was for your sake that I allowed Zhang Xiu to submit; otherwise I would have slain him and cut him off root and branch,” said Cao Cao. “Indeed, then, I owe my very life to you; I am very grateful,” said she. “To see you is a glimpse of paradise, but there is one thing I should like better. Stay here and go with me to the capital where I will see that you are properly cared for. What do you say to that, my lady?” She could but thank him. “But Zhang Xiu will greatly wonder at my prolonged absence, and gossips will begin to talk,” said she. “If you like, you can leave the city tomorrow.” She did so, but instead of going at once to the capital, she stayed with him among the tents, where Dian Wei was appointed as a special guard over her apartments. Cao Cao was the only person whom she saw, and he passed the days in idle dalliance with the lady, quite content to let time flow by (Luo, 2019, p. 148)

An openness to women’s remarriage (widows’ remarriage in particular) was part of the ethos of the Han Dynasty and the Three Kingdoms period. And there is no lack of such cases in the fiction, such as widowed Lady Wu’s remarriage to Liu Bei, Lady Zhen’s remarriage to Cao Pi, and Zhao Fan’s attempt to marry his widowed sister-in-law to Zhao Yun. Lady Zou’s husband Zhang Ji had died and his nephew Zhang Xiu had already surrendered to Cao Cao. Given that, she did not really have any other choice in front of Cao Cao and his troops. Besides, Cao Cao was, so to speak, a “hero” of his time. But Lady Zou did not seem to be listed among women like Lady Zhen. A bias against Zou can be traced in the author’s spatial narrative. First, the space where Zou was seen was quite ambiguous. She was peeped at by Cao Anmin, nephew of Cao Cao in “one of the courts” through “one of the partitions” in the evening. Cao Anmin described her beauty to Cao Cao, who thus changed his mind of killing time with singing girls. Lady Zhen, however, was met by Cao Pi as a result of Cao Pi’s intrusion into the private rooms of Yuan Shao’s residence. Second, it was Lady Zou that proposed to leave the city to avoid suspicions and gossips. So Cao Cao agreed and took her out of the city and stayed among the tents. “He passed the days in idle dalliance with the lady, quite content to let time flow by.” Judging solely from the results, Lady Zou inadvertently accomplished a beauty trap that led to the death of Cao Cao’s beloved son, nephew and senior general. But evidently, Lady Zou was not put on a par with Diao Chan by the author, and there is no account of Zou’s whereabouts later in the fiction. So what was it that differentiated Zou from Diao Chan? The answer is clear: Zou’s cross-space movement was not entrusted by male authorities, but merely out of the selfish calculation, while Diao Chan’s cross-space movement was entrusted by male authorities and motivated by a strong sense of loyalty and righteousness. To put it another way, the case entrusted by male authorities or motivated by loyalty and righteousness could be deemed a “beauty trap;” the case not entrusted by male authorities, but merely out of selfish calculation could only be considered “water of disaster” (a curse). Essentially “beauty trap” and “water of disaster” were two sides of the same coin.

In general, women did not have much presence in external spaces, where they could only be seen for reasons such as war, migration, marriage and visits to parental homes. Women who passively moved between spaces often assumed the image of victims, whereas women who actively moved between spaces were either entrusted by male authorities or driven by a sense of loyalty and righteousness. However, the women’s cross-space movement was only transient and exceptional and could not last long. Returning to feminine space was the norm. When a woman’s movement between spaces was not forced, or entrusted by any male authority, or driven by a sense of loyalty and righteousness, she would fall under suspicion of improper behavior. Whether active or passive, their very presence in external spaces still shows that women in the Han Dynasty and the Three Kingdoms period enjoyed more freedom to move between spaces than women in later dynasties.

Women’s Reversal of Power in Spatial Representation

According to the theory of feminism, the status gap between men and women is increasingly reinforced through spatial arrangement; gendered spaces form a barrier to women’s access to knowledge, and this barrier is further exploited by men in the process of reproduction; gendered spaces, which are manipulated by men, become spaces of power (Dong, 2013, p. 141). Although space power is held by men, women are not precluded from achieving a certain reversal of power in local spatial domains. If for some reason women acquire some knowledge and abilities not available to them under “gender segregation,” they have the chance to take control of space power partly or temporarily.

The reversal of power can be exemplified by Diao Chan in the beauty trap. The whole beauty trap was plotted and supervised by Wang Yun. Yet, it can be seen from Diao Chan’s perspective that she was a voluntary space transgressor and controller. She was sighing deeply in the private garden late at night, and deliberately made her sighs overheard by Wang Yun. That was how this beauty trap started. Then, she was sent from Wang’s residence to Dong’s, where she improvised to divide Dong Zhuo and his foster son Lü Bu. She met Lü Bu in the garden and let Dong Zhuo discover it. Thus, a grudge grew between the two and eventually encouraged Lü Bu to kill Dong Zhuo. From Wang’s residence to Dong’s residence, Diao Chan always remained in control of space power. Prior to Diao Chan, there were several heroes, including Cao Cao, attempting to assassinate Dong Zhuo, but they all failed. Diao Chan made it thanks to her extraordinary wisdom and adaptability to changes, which far surpassed that of the aforementioned men.

Diao Chan’s accomplishment of the mission had a lot to do with her background and experience. She was an entertainer, or rather, a household courtesan in Wang Yun’s residence. Household courtesans referred to female entertainers (singers and dancers) who served in the houses of the nobility and bureaucrats, and they evolved from “palace courtesans” (female entertainers in the palace).

From the reign of Jie of Xia, female musicians/entertainers remained the lower orders. From the Western Zhou Dynasty to the end of the Qing Dynasty, they were deemed a group of “pariahs.” And a gradient of “inferiority and superiority” was at the core of the feudal system. A ban on marriage between commoners (liangmin) and pariahs (jianmin) remained in effect in imperial China since the Zhou and Qin dynasties and was particularly highlighted in legal provisions by the ruling class from the Han to the Tang Dynasty. (Cheng, 2019, p. 24)

It was a tradition for the nobility and bureaucrats to keep female musicians/entertainers, who functioned differently from their wives and concubines. More specifically, these entertainers were mainly engaged in singing, dancing, and acting on recreational or ceremonial occasions. And Diao Chan was no exception to that. She belonged to a pariah whose job was to entertain prominent officials and eminent personages and play a due part in various ceremonies held by her master’s family. But her job as a lowly entertainer precisely enabled her to cross the line between gendered spaces and see a bigger world during the performance, which was impossible for women from an aristocratic or decent family.

Having seen all sorts of people, she gradually developed an ability to read the minds of various bureaucrats, and grasp their power relations and conflicts of interest. That explains why she was able to fascinate both Dong Zhuo and Lü Bu and played well with them without arousing any suspicion. (Li, 2009, p. 91)

There was already an air of easy assurance and calm about her right from the very beginning. When Wang Yun was worried about the consequences of their possible failure and said, “But if this gets abroad, then we are all lost!” She just replied, “I must do my best…Fear not” (Luo, 2019, p. 66).

The spatial narrative about Lady Sun is also worth studying. Initially, she seemed to be a puppet at the mercy of authorities. She was the mainspring of the cross-space movements of multiple characters (Sun Quan, Liu Bei, Dowager Marchioness, etc.) but was never present. It was not until her presence in the “bridal chamber” that a significant reversal of space power appeared. Below is an excerpt:

Liu Bei was very happy, and there were fine banquets, and the bride and bridegroom duly plighted their troth. And when it grew late and the guests had gone, the newly wedded pair walked through the two lines of red torches to the nuptial apartment. To his extreme surprise, Liu Bei found the chambers furnished with spears and swords and banners and flags, while every waiting-maid had girded on a sword. The bridegroom turned pale: bridal apartments lined with weapons of war and waiting maids armed! But the housekeeper of the princess said, “Do not be frightened, O Honorable One. My lady has always had a taste for warlike things, and her maids have all been taught fencing as a pastime. That is all it is. “Not the sort of thing a wife should ever look at,” said Liu Bei. “It makes me feel cold and you may have them removed for a time.” The housekeeper went to her mistress and said, “The weapons in your chamber displease the handsome one; may we remove them?” Lady Sun laughed, saying, “Afraid of a few weapons after half a lifetime spent in slaughter!” But she ordered their removal and bade the maids take off their swords while they were at work. (Luo, 2019, pp. 466-467)

Lady Sun, who was originally supposed to be a victim of the political alliance between Liu Bei and Sun Quan, somehow managed to reverse this spatial cognition. She furnished her chambers with spears and swords and even laughed at Liu Bei, saying, “Afraid of a few weapons after half a lifetime spent in slaughter!” From her words and deeds, one can see that Lady Sun came out on top from inside to outside. The whole scene was entirely different from the usual picture of a bridal chamber. The previous spatial imagination about Lady Sun as part of a beauty trap was thus subverted. She was neither a key figure in a beauty trap like Diao Chan, nor a victim of patriarchy like the daughter of Lü Bu. Diao Chan appeared in the sleeping apartment, at the window, in front of the dressing table, behind the screen, and in the private garden as she advanced the beauty trap. These spaces were combined to form a private vibe that was enchanting and erotic. Lü Bu’s daughter was used by him as a pawn in a political deal. Once, Lü Bu “chose some good horses and had a wedding carriage made ready” for her daughter. Before long, he found he had been set up, and thus took her back. Later, “Lü Bu wrapped up his daughter in soft wadded garments, bound her about with a mailed coat, and took her on his back” to get through the close siege. His daughter was more like a sacrifice, having not spoken a single word from her first appearance to the end. Lady Sun, benefiting from being Sun Quan’s younger sister, “has always had a taste for warlike things, and her maids have all been taught fencing as a pastime;” and her taste for warlike things was, in Liu Bei’s view, “not the sort of thing a wife should ever look at.” She acquired some knowledge and abilities not available in feminine space, and thereby secured certain space power. On the wedding night, brides were often admired by their bridegrooms for being gentle and sweet. But that expectation was quite the opposite to what Liu Bei saw and felt in the “chambers furnished with spears and swords and banners and flags, while every waiting-maid had girded on a sword.” He had an “extreme surprise” and “turned pale.”

Lady Xu, who was the wife of Sun Yi, was a famous heroine of the Eastern Wu. She crossed the line of gendered spaces and took control of space power to avenge her husband. Beautiful and talented, “Lady Xu was skilled in divination.” On the day of her husband’s death, she cast a most inauspicious lot. Wherefore she besought her husband not to go for the assembly. But he was obstinate and went and was stabbed to death. After her husband’s death, Lady Xu was compelled to marry her foe. She was not terrified and pretended to favor the proposal and said “Yes” to gain time. Then she sent for two old generals of her husband’s. Together, they came up with a plan in her residence. One day, Lady Xu called in the two generals and hid them in a secret chamber. Then she invited her suitor to her reception room, where she entertained him at supper. When he had well drunk, she led him to the chamber where the generals were waiting. As soon as the drunken man entered the room, the two generals rushed out and had him killed. By inviting men into her residence for a secret meeting, drinking with a man in the reception room, and leading the man into the secret chamber, Lady Xu crossed the line between gendered spaces again and again. Nevertheless, she did so in order to avenge her husband, so what she did was justifiable. During the process of revenge, Lady Xu only moved among the great hall, the reception room and the secret chamber inside her residence, but she took full control of space power.

Whether it is Diao Chan, Lady Sun, Lady Xu, or any other woman who gained space power, their exercise of space power was without exception temporary. Diao Chan, a fictional character, lost her space power and went with Lü Bu immediately after her accomplishment of the beauty trap. Later, when Lü Bu hesitated about how to survive a crisis, Diao Chan, then a concubine of Lü Bu, became timid and weak. She said, “You are my lord and my life. You must not be careless and ride out alone” (Luo, 2019, p. 170). Such a response was in stark contrast with her debut when she reassured Wang Yun, “I must do my best……Fear not.” This was a rift in the textual narrative which the author could not add up. Lady Sun’s marriage to Liu Bei, which was not a happy and harmonious one, was also “rewritten” by the author.①According to the Records of the Three Kingdoms (San Guo Zhi), the marriage between Lady Sun and Liu Bei did not seem to be a happy and harmonious one. As recorded in the “Biography of Fa Zheng,” the Records of the Three Kingdoms: In the beginning, Sun Quan arranged for his younger sister to marry the late lord (Liu Bei). His sister was very much as talented and fierce-tempered as all of her elder brothers. She had over a hundred maidservants, all of whom stood by holding swords. Every time when the late lord (Liu Bei) entered her chambers, he always felt cold and terrified. (Chen, 2009, p. 328) Also, as recorded in the “Biography of Zhao Yun,” the Records of the Three Kingdoms: At the time, Lady Sun, the late lord’s wife, who was arrogant and imperious as Sun Quan’s younger sister, connived at the wrongdoings of the troops she had brought with her from Eastern Wu (State of Wu). The late lord (Liu Bei) thought that Zhao Yun, who was calm and unhurried, was sure to have them subdued and therefore deliberately let Zhao in charge of internal affairs (while he was away). Having heard of Liu Bei’s western expedition, Sun Quan sent a fleet of ships to take his younger sister back. And Lady Sun attempted to take the heir apparent (Liu Shan) along with her to Wu, only to be stopped by Zhao Yun and Zhang Fei with troops on the river. Eventually, the heir apparent was returned safely (Chen, 2009, p. 324).In the fiction, after Lady Sun’s return to Eastern Wu, she remained loyal to Liu Bei for the rest of her life; after receiving the rumor of Liu Bei’s death, she even threw herself into the stream and was drowned. As for Lady Xu, her space power was transferred after the revenge was fulfilled. “Very soon her brother-in-law (Sun Quan) came with an army (to Danyang)… He took the widow to his own home so that she would be cared for” (Luo, 2019, p. 335).

Conclusion

In short, space is dynamic and constructive, and so is gendered space. The feminine space inRomance of the Three Kingdomswas constructed based on “gender segregation.” The female characters mainly stayed in the “backyard” of homesteads, and were rarely seen in external spaces. And when they did show up outside the “backyard,” they were mostly under male domination or protection. Whether inside or outside the home, space power remained in the hands of men. However, thanks to certain special opportunities, status, or class, women could acquire some knowledge and abilities not available to them in the feminine space. Under such circumstances, they had the chance to reverse the space power and temporarily take control of it. Regarding the construction of gendered space inRomance of the Three Kingdoms, some conflicts and even paradoxes arose between different intentions of space construction, and thereby formed rifts in the textual narrative. To some extent, such rifts highlight the richness and complexity of feminine space and circumstances in the late Han Dynasty, as well as the diversity of ways in which women acquired space power.

Contemporary Social Sciences2021年6期

Contemporary Social Sciences2021年6期

- Contemporary Social Sciences的其它文章

- A Study of the European Union’s Path for Constructing Digital Governance Rules and the Logical Implications of the Path

- 《当代社会科学(英文)》稿件格式参考

- Does Environmental Regulation Increase Employment? Based on the SCM and RCM Methods

- The Influence of Sichuan–Tibet Railway on the Accessibility and Economic Development of City Propers along the Line: Taking Chengdu and Ya’an as Examples

- A Study of Idiom Translation in Bonsall’s The Red Chamber Dream

- Wang Chuan’s Abstract Painting: A Contemporary Expression of Chinese Zen Ink Painting