畜禽养殖场颗粒物污染特征及其危害呼吸道健康的研究进展

戴鹏远,沈丹,唐倩,李延森,李春梅

畜禽养殖场颗粒物污染特征及其危害呼吸道健康的研究进展

戴鹏远,沈丹,唐倩,李延森,李春梅

(南京农业大学动物科技学院,南京 210095)

随着畜禽养殖集约化程度的提高,高密度饲养引起畜禽养殖场空气质量问题日益突出,特别是养殖舍内环境颗粒物(particulate matter:PM)污染引起的家畜呼吸道健康问题不容忽视。畜禽养殖生产过程中可产生大量PM,已成为大气细颗粒物PM2.5(空气动力学直径小于等于2.5 μm)和PM10(空气动力学直径小于等于10 μm)的重要来源,影响大气环境空气质量。畜禽养殖场的PM主要来源于饲料、粪便、羽毛、皮屑等,其成分主要是有机物,含有C、H、O、N、S、Ca、Na、Mg、Al和K等多种元素;PM表面还附着细菌、真菌、病毒等多种微生物以及内毒素、氨气、硫化氢等有害物质。畜禽养殖舍PM的产生和释放受到家畜的种类、日龄、活动以及季节等多种因素的影响,鸡舍内PM的浓度高于猪舍,冬季舍内PM的浓度高于夏季。但是,目前缺少标准化设备和标准方法来测量不同类型的畜禽舍PM的浓度和排放水平。畜禽养殖舍PM的成分复杂,具有很强的生物学效应,严重危害家畜的健康和生产。畜禽舍内高浓度PM主要通过以下3种形式影响呼吸道健康,一是PM直接刺激呼吸道,降低机体对呼吸系统疾病的免疫抵制;其次是PM表面附着的多种化合物的刺激;第三种是PM表面的病原性和非病原性微生物的刺激。目前关于PM对呼吸道健康危害机制的研究主要集中在PM对呼吸道的致炎作用,研究发现:PM通过刺激肺泡巨噬细胞产生前炎症因子,继而诱发其它细胞释放炎症因子,引起肺发生炎症反应;另外,PM2.5通过引起肺组织细胞发生氧化应激,激活丝裂原活化蛋白激酶 (MAPKs)活性,上调核转录因子κB (NFκB) 和转录激活因子AP-1的表达而诱发肺的炎症; PM2.5也可通过激活模式识别受体Toll样受体TLR2和TLR4的表达,激活NFκB信号通路而导致炎症的发生。也有研究发现,PM2.5在诱导呼吸道炎症的同时,还会激活细胞自噬和核因子相关因子-2(nuclear factor E2-related factor 2,Nrf2)相关信号通路,这为缓解和治疗PM引起细胞损伤提供了靶点。尽管PM危害呼吸道健康的机制研究较多,但是PM成分复杂,并处在不断变化中,因此PM诱导呼吸道损伤的机制也十分复杂,仍需进一步系统深入研究。畜禽养殖生产过程中释放的大量PM严重影响环境空气质量和家畜健康,而PM对环境和家畜健康的危害程度与其组成和浓度密切相关。因此,正确认识畜禽舍PM的形态、大小、组成、浓度水平及其形成排放影响因素,对确定畜禽舍PM的来源和PM的毒性危害具有重要意义。文章就畜禽生产过程中产生的PM的来源、化学组成、浓度、排放、影响因素,以及PM对呼吸道功能的影响及作用机制作一综述,为正确评估PM对畜禽健康生产的影响提供参考依据。

畜禽舍; 颗粒物; 污染特征;呼吸道危害

畜禽生产过程中产生并释放大量的颗粒物(particulate matter,PM)对家畜的健康和生产以及现场工作人员健康产生不利影响。PM通过呼吸进入呼吸道,严重危害动物和人的呼吸道健康[1,2]。长期暴露于PM2.5浓度较高鸡舍的生产管理一线人员,易患呼吸道疾病、哮喘以及慢性阻塞性肺病[3]。另外,舍内PM通过通风设施排放到大气中,还会对大气造成污染。有研究表明大气中PM10和PM2.5的8%和4%来自于畜禽生产[4-5]。据报道,荷兰大气中PM的25%来自于农业[6];欧洲集约化的禽舍和猪舍是大气PM的重要来源,分别占到50%和30%[7]。高浓度的PM除了影响大气环境,还会影响云的形成、大气可见度等[8]。畜禽舍PM表面附着氨气、恶臭化合物及微生物等,这些物质增强了PM的毒性。因此,正确认识畜禽舍环境中PM的形态、大小、组成、浓度水平及其形成和排放影响因素,对确定畜禽舍PM的来源和PM的毒性危害具有重要意义。本文针对畜禽生产过程中产生的PM的来源、化学组成、浓度、排放、影响因素,以及PM对呼吸道功能的影响及作用机制作一总结,为正确评估PM对畜禽健康生产的影响提供参考依据。

1 PM的基本特征和分类

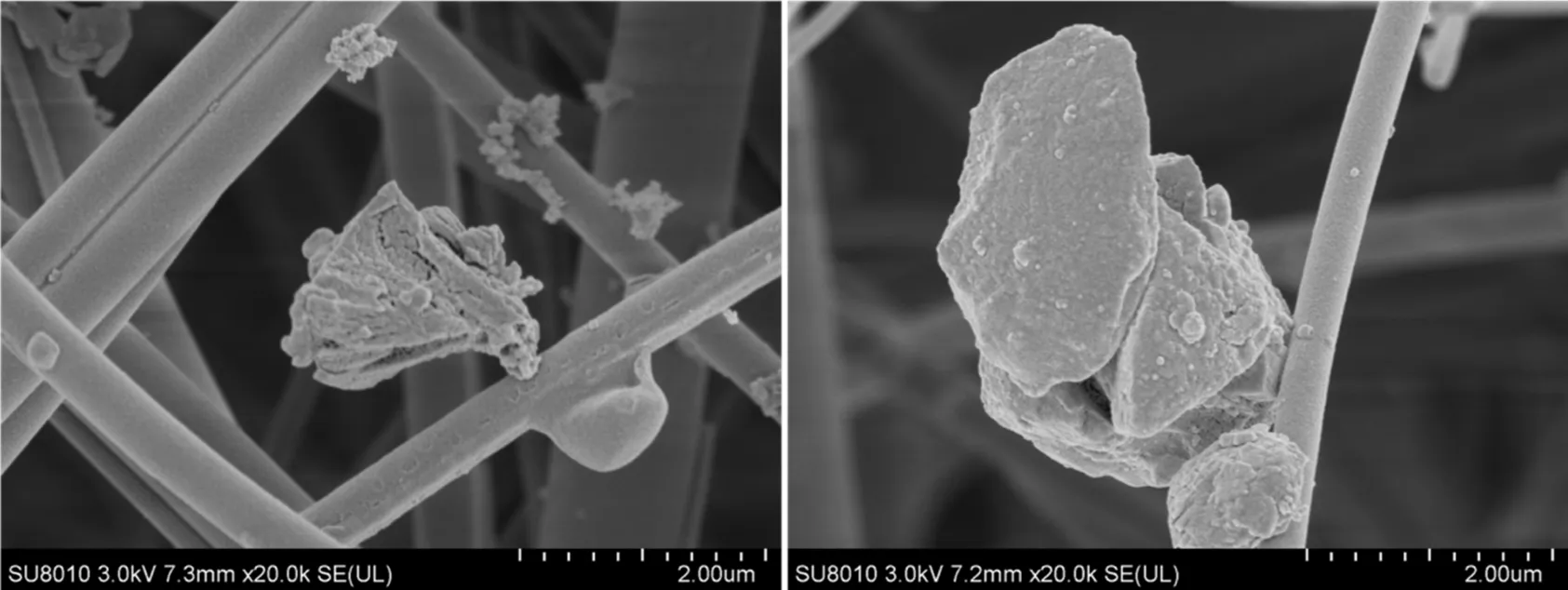

大气PM一般是指粒径小的、分散的、悬浮在气态介质中的固体或气体粒子。大气PM一般可分为初级PM和次级PM。初级PM是直接释放到大气中的粒子,包括土壤粒子、海盐粒子、生物碎片等;次级PM是指大气中污染气体组分与正常气体组分通过化学反应生成的PM。根据PM的形成和来源不同,其性质、形状、大小、密度和化学组成也不尽相同,这就造成了PM的异质性[9]。这种异质性同样适用于畜禽舍中的PM。图1是鸡舍中PM2.5电镜图片,颗粒物呈现出薄片状、椭圆形以及晶体状,直径在几纳米到十微米之间[10]。畜禽舍内的PM浓度一般为其它室内PM浓度的10—100倍,它是多种气味化合物及氨气、硫化氢等气体的载体,其表面一般附着多种不同种类的微生物[11]。

通常,采用空气动力学当量直径(aerodynamic equivalent diameter, AED)来描述大气粒子大小。不论粒子形状、大小和密度如何,当它与密度为1 g·cm-3球体粒子沉降速度一致时,该球体的直径就是该粒子的直径。对于不规则形状的颗粒物,这个直径是一个有用的测量指数,因为具有相同AED的粒子悬浮在空气中的行为表现可能相同[12]。

颗粒物的分类方法主要有沉降特性法、粒子大小法和健康大小法。按照沉降特性法,颗粒物分为降尘和飘尘。降尘一般是指粒径大于10 μm的粒子,它们在空中易于沉降,速度大约为 0.3 cm /s,当粒子直径大于30 μm时,沉降速度为1 cm /s。飘尘是指粒径小于10 μm,能在空气中长期漂浮的粒子。根据粒子大小法,颗粒物可分为总悬浮颗粒物(total suspended particulates, TSP,粒子直径0—100mm),粗颗粒物(粒子直径介于2.5—10 μm,PM2.5-10),细颗粒物(粒子直径小于 2.5 μm,PM2.5)和超细颗粒物(粒子直径小于0.1 μm,PM0.1)。健康大小法是根据颗粒物进入呼吸道不同深度来进行分类的。国际标准化组织规定将直径小于等于10 μm 的颗粒物定为可吸入颗粒物,在可吸入颗粒物中,大于5 μm的粒子被阻挡在上呼吸道,小于5 μm的粒子进入气管和支气管,而粒径小于2.5 μm的粒子能进入肺泡,这部分颗粒物称为可呼吸颗粒[13]。

图1 鸡舍中不同来源PM的扫描电镜图片

2 畜禽舍PM的特征

2.1 畜禽舍PM的来源

有关畜禽舍PM来源的相关研究已有较多报道,主要集中在猪舍和鸡舍。猪舍中的PM主要来源于饲料和粪便[14-15],育肥猪舍中的PM含有较高浓度的氮,这表明饲料、动物皮屑和其它含氮化合物为舍内PM的主要来源[16]。另外,霉菌、谷物、昆虫以及矿物质粉尘也是猪舍PM的来源[14]。根据颗粒物大小的源解析表明,猪舍中PM的5%—10%来源于皮肤,粒径在7—9 μm的粒子占5%,粒径为11—16 μm的粒径占10%[17]。在肉鸡舍中,PM的主要来源为鸡绒羽、尿中的矿物晶体以及废弃物[18]。蛋鸡舍PM的主要来源包括皮屑、尿液、饲料及废弃物[19]。另外,与无垫料鸡舍相比,有垫料鸡舍里垫料也是PM的主要来源[20-21]。在生长育肥猪舍内,含有稻草垫料猪舍比混凝土地板猪舍PM浓度高两倍,尤其在育肥后期舍内PM浓度更高,这是因为在后期,垫料更脏,易被分解产生更多的颗粒物[20]。

2.2 畜禽舍PM的化学组成

畜禽舍内90%的PM由有机粒子组成[22],主要有生物来源的初级粒子,如真菌、细菌、病毒、内毒素及过敏原,还有来源于饲料、皮肤和粪便的粒子等[14]。舍内PM的组成成分与家畜种类、畜禽舍废弃物(畜禽粪便、畜禽舍垫料、废饲料及散落的毛羽等废物)的组成有关[23-24]。畜禽舍PM成分中主要的元素为C、O、N、P、S、Na、Ca、Al、Mg和K[15, 25]。猪舍和禽舍内的PM富含N元素,而来自于牛舍的PM中N元素含量少。牛舍中PM湿度较大同时含有较多的矿物质和灰烬[26]。对育肥猪舍PM成分分析结果发现,Na、Mg、Al、P、S、Cl、K及Ca 含量较高[20]。也有研究报道,猪舍内不同粒径的PM中P、N、K及Ca含量较高[27]。粪便粒子含有较高的C、P和较高的有机磷酸酯和焦磷酸盐[28]。在肉鸡舍中不同来源的PM2.5和PM10中含有的元素成分不同,粪便来源的PM中N,Mg,P和K元素含量最高;皮肤来源的PM中S元素含量最高;木屑来源的PM中Na和Cl元素浓度最高;饲料来源的PM中Si和Ca元素含量最高;舍外的PM2.5中Al元素含量最高[29]。

2.3 畜禽舍PM的浓度、排放及其影响因素

畜禽舍内PM的浓度取决于多种因素,包括家畜的种类、饲养方式、活动情况、饲养密度以及舍内环控系统、舍内湿度、季节及采样时间等[25,30]。猪舍内PM的浓度和排放与舍内的通风率、湿度及猪的活动量、饲养管理、体重及育肥状态有关[31,32]。多因子线性分析揭示了在肉鸡舍中,通风效率、垫料类型、舍内温度、建筑物年限对舍内PM10的浓度影响较大,而舍内PM2.5的浓度与舍内鸡数量、通风水平及湿度有关[33]。通风率,温度和相对湿度是影响PM形成的重要因素,它们决定了PM的形成、排放过程和粒子分布[25,34-35]。在肉鸡舍中的研究结果表明,舍内温度和相对湿度对TSP浓度影响较大[18, 36]。

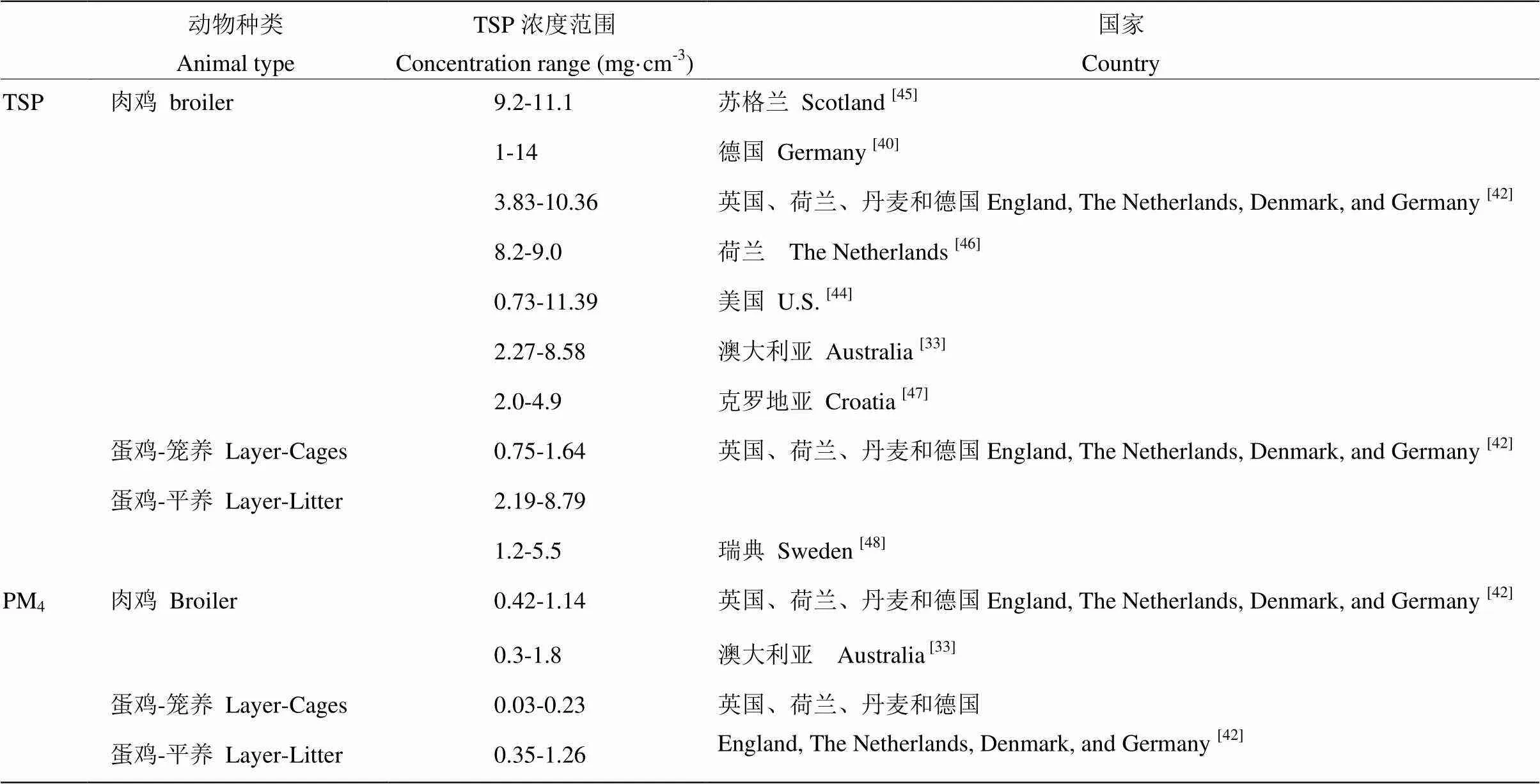

2.3.1 不同家畜种类对舍内PM浓度的影响 CAMBRA-LóPEZ 等[37]对不同畜舍内PM浓度进行监测分析对比发现,禽舍中PM的浓度高于猪舍,肉鸡舍PM浓度高于笼养蛋鸡舍,火鸡舍中TSP浓度为1.3—7.5 mg·cm-3,与肉鸡舍中TSP浓度相近。牛舍中PM浓度相对较低,奶牛舍中TSP浓度低于1 mg·cm-3[38-39]。表1和表2分别总结了禽舍和猪舍中TSP和PM4监测到的浓度范围。禽舍中的PM浓度高于猪舍,肉鸡舍中的PM浓度高于蛋鸡舍,平养蛋鸡舍PM浓度高于笼养蛋鸡舍。

2.3.2 家畜日龄对舍内PM浓度的影响 有研究报道,肉鸡舍PM的浓度随着肉鸡日龄的增加呈线性增长[40]。YODER等[41]也研究发现禽舍PM2.5的浓度随动物日龄的增加呈现对数增长。禽类日龄增加引起舍内PM浓度升高可能是因为随着动物日龄的增长,干粪增多,鸡活动增强,羽毛量增多等原因。相反,猪舍内PM10浓度随着猪体重的增加而降低,这可能是因为随着体重增加,猪的活动量减少的原因[40]。

2.3.3 家畜活动对舍内PM浓度的影响 每天的喂料时间以及光照程序会通过影响家畜活动来影响舍内PM的形成和浓度。白天,由于喂料和养殖人员的活动,家畜采食等活动量增多,易引起畜舍建筑物表面的PM分散,使舍内PM浓度上升[42]。相对于肉鸡,蛋鸡在白天的活动量较大,因此蛋鸡舍内PM的浓度相对较高[42-43]。另外,光照也会影响畜禽舍内PM浓度的变化。在鸡舍中,光照较强位置处的PM浓度明显高于黑暗处,这是因为在光照下动物活动增强[19]。在间歇性光照程序的肉鸡舍中,舍内PM浓度与光照时间及动物活动具有很强的关系。在猪舍中,PM10在喂料时间明显升高,白天PM浓度高于夜间[32,40]。这些结果充分说明,动物活动与PM浓度密切相关,任何能引起动物活动的因素均会影响PM的浓度和分布。

2.3.4 季节因素对舍内PM浓度的影响 季节因素引起的PM浓度变化与舍内通风率密切相关[44]。增加通风率可降低畜禽舍内PM浓度,夏季舍内的通风率比冬季高,因此夏季舍内PM的排放率较高,舍内PM浓度较低[44]。研究表明,不论鸡舍还是猪舍,夏季的舍内PM浓度低于冬季[42]。HINZ等[40]研究发现,当夏季舍内外温差小于10℃时,肉鸡舍内PM的浓度低于冬季舍内外温差大于10℃时的浓度。舍内外较小的温差与高通风率相关,这些进一步说明通风率对PM浓度具有很大影响。

3 畜禽舍PM对呼吸道健康的危害及其可能机制

3.1 畜禽舍PM对呼吸道健康危害

畜禽舍内高浓度PM容易引起家畜呼吸道疾病[53-54]。PM通过以下3种方式影响呼吸道健康,第一种是PM直接刺激呼吸道,降低机体对呼吸系统疾病的免疫抵制;其次是PM表面附着的化合物的刺激;第三种是PM表面病原性和非病原性微生物的刺激[55]。第一种方式是颗粒物本身引起的呼吸道损伤[53, 56],此种方式同时与第二和第三种方式相关[57-58]。畜禽舍PM的表面附着大量的重金属离子、挥发性有机化合物(volatile organic chemicals, VOCs)、NO3-、SO42-、NH3、臭味化合物、内毒素、抗生素、过敏原、尘螨及β-葡聚糖等物质[59-60],这些物质以PM为载体进一步危害呼吸道健康。PM影响呼吸道健康的第三种方式与生物气溶胶相关,PM表面附着的大量细菌、真菌和内毒素,易引起呼吸道感染[61- 62]。畜禽舍空气中革兰氏阴性菌所占比例尽管低于10%,但所有的革兰氏阴性菌均具有致病性[63]。内毒素是革兰氏阴性菌细胞膜中的脂多糖成分,在畜禽舍周围内毒素的浓度高达0.66—23.22 EU(endotoxin units)/m3[64],在牛舍中内毒素浓度最高可达761 EU/m3[65],散养蛋鸡舍的内毒素最高浓度可达8120 EU/m3[66]。这些高浓度的内毒素不仅可引起家畜呼吸道和肺部感染,同时也危害养殖工作人员及其周边居民的呼吸道健康[67-68]。致病性生物气溶胶不仅可以直接损害家畜呼吸道健康,还可以通过空气传播扩散到邻近农场[52]。

表1 肉鸡舍和蛋鸡舍内TSP和PM4的浓度

表2 猪舍内TSP和PM4的浓度

有关畜禽舍PM损害呼吸道功能的研究已有很多文献报道,但这些研究多集中在体外试验研究。有研究报道,猪场内的颗粒粉尘导致人类肺泡巨噬细胞和支气管上皮细胞的炎症因子白细胞介素-8(IL-8)、白介素-12(IL-12)和IFN-γ表达上调,提高活化T细胞的百分率[69],并增强对呼吸感染的易感性[70]。另外,近年来有些研究者对猪舍内有机灰尘的提取物(organic dust extract,ODE)进行的体内和体外试验研究发现,ODE不仅能引起猪呼吸道和肺部的炎症,导致肺部细胞发生凋亡[71],增加炎症细胞数[72-73],还可降低炎症细胞的吞噬能力以及细菌杀伤能力[74],引起呼吸道的高反应性[75]。MITLOEHNER等[76]研究发现奶牛场PM可降低奶牛场工作人员的肺活量,这与亚急性呼吸道损害相关。

3.2 畜禽舍PM诱导呼吸道炎症反应机制

3.2.1 PM诱导肺泡细胞炎症反应的机制 PM引起的呼吸道危害主要与肺部炎症相关,因此下面集中讨论PM诱导的肺炎症反应的相关机制。吸入的PM能刺激肺泡巨噬细胞产生前炎症因子,前炎症因子刺激肺泡的上皮细胞、内皮细胞及成纤维母细胞分泌细胞因子和黏附因子,诱导炎性细胞聚集,引发炎症反应[77]。PM诱导炎症反应的一个重要机制是氧化应激[78],氧化应激是活性氧(reactive oxygen species, ROS)的产生与抗氧化体系不平衡所造成的[79]。PM能刺激机体呼吸道组织细胞产生ROS,而ROS能激活氧化还原敏感性信号转导通路,如丝裂原活化蛋白激酶(MAPKs)和磷脂酰肌醇-3-激酶/蛋白激酶B (PI3K/AKT)通路[80-82]。MAPKs包含一组丝氨酸/苏氨酸蛋白激酶(c-Jun NH2-末端激酶,JNK;胞外信号调节激酶,ERKs;应激激活蛋白激酶,p38),它们能在细胞外应激源的刺激下被激活,调节从细胞表面到核的信号转导,最终导致致炎因子的表达上调而引起细胞炎症反应[83]。有研究报道,PM可诱导人和鼠的肺泡巨噬细胞产生过多的ROS,进而激活MAPKs,诱导转录激活因子AP-1的表达上调,诱发细胞炎症反应[84]。柴油机废气粒子能诱导人气管上皮细胞产生ROS,激活ERK1/2和p38,继而激活下游的核转录因子κB(NFκB), 最终诱发细胞发生炎症反应[85]。钙离子(Ca2+)是维持生命活动不可缺少的离子,其在凝血、肌肉收缩、神经递质的合成与释放、机体免疫功能方面发挥重要的作用[86-87]。研究发现,PM引起肺泡上皮细胞的氧化应激刺激Ca2+从细胞内质网中释放出来,调节转录因子NFκB的表达,促进炎症因子表达的上调[88]。

PM诱导细胞炎症反应的另一机制是通过Toll样受体(TLRs)信号通路[89-90]。TLRs是一种模式识别受体(pattern recognition receptor, PRR),表达于固有免疫细胞表面,能识别一种或多种病原体相关分子模式(pathogen-associated molecular patterns, PAMP), 在先天性免疫和获得性免疫系统中发挥作用,目前发现TLR受体共有13种,包括TLR1-13[91-92]。大量研究发现,大气粒子污染物能激活细胞模式识别受体TLR2和TLR4[93-95]。髓样分化因子88(MyD88)和TIR 结构域衔接蛋白(TRIF)是粒子暴露引起表达的潜在下游蛋白,它是所有TLRs的接头蛋白[96-97]。以小鼠为模型急性感染ODE引起的炎症反应主要是通过MyD88信号通路[98]。肺巨噬细胞在PM的刺激下,TLR4与TRIF 相关接头分子(trif-related adaptor molecule,TRAM)结合招募 TRIF,进而激活p38, 引起下游炎症因子表达上调,最终导致细胞发生炎症反应[84]。

3.2.2 PM诱导呼吸道损伤的可能缓解机制 自噬是一种进化上保守并且与溶酶体信号通路相关的过程,它通过多重通路降解蛋白质、糖原、脂质、核苷酸等大分子以及细胞器[99]。自噬被证明参与许多生理过程,包括宿主防御,细胞生存和死亡[100]。近来研究发现PM暴露可诱导细胞自噬发生。邓等[101]利用腺癌人类肺泡Ⅱ型上皮细胞(A549细胞)研究发现,PM2.5可诱导A549细胞自噬标志蛋白LC3Ⅱ以一种时间和浓度依赖的方式累积,并且促进自噬起始蛋白Beclin1和相关基因Atg5的高表达。PM2.5暴露大鼠肺巨噬细胞和小鼠腹腔巨噬细胞,可诱导细胞ROS产生,激活PI3K/AKT信号通路,同时降低自噬中心蛋白—哺乳动物雷帕霉素靶蛋白(mammalian target of rapamycin, mTOR)的表达,增强了LC3Ⅱ的产生[102-103]。AMP依赖的蛋白激酶(AMPK)负责细胞能量代谢,它能被外界各种应激源刺激激活,以保持机体葡萄糖代谢平衡。另有研究发现,PM2.5可激活A549细胞AMPK的表达,进而抑制mTOR的表达,同时促进自噬核心蛋白ULK1的表达[104]。细胞自噬和炎症反应关系十分密切。细胞在PAMP刺激下引发炎症和自噬,而自噬对炎症具有负调节作用[105]。自噬抑制炎症发生的机制可能是通过降低细胞内ROS水平实现的。自噬能抑制细胞内线粒体的聚集,及时清除胞内的过氧化物酶体,进而减少由ROS诱导的炎症反应[106-107]。

核因子相关因子-2(nuclear factor E2-related factor 2,Nrf2)是一种转录因子,细胞在正常状态下,Nrf2与Keap1结合被锚定胞质,应激发生时,Keap1被降解,Nrf2解离进入细胞核与抗氧化反应原件(antioxidant response element, ARE)结合,进而启动下游抗氧化基因的转录表达。细胞在外界应激源刺激下产生ROS,使细胞发生氧化应激,而过量的ROS又激活了Nrf2抗氧化信号通路,从而减轻细胞的氧化损伤。PM2.5暴露A549细胞,可诱导细胞产生ROS, 而ROS激活Nrf2抗氧化信号通路,从而减轻PM2.5对细胞的毒性损伤。除了PM刺激,研究证明Nrf2信号通路在多种肺部炎症性疾病中发挥作用[108]。当肺部组织受到有毒有害物质刺激时,Nrf2信号通路能被激活,上调抗氧化基因的表达,进而减轻因应激因素造成的肺损伤。此外,也有研究报道,急性肺炎治疗的药物主要通过上调细胞Nrf2的表达,抑制NFκB和AP-1生成,降低炎症因子表达而最终起到消炎作用[109]。综合上述,用图4总结概述PM诱导细胞炎症反应、自噬和Nrf2信号通路的可能机制。

图2 PM诱导细胞炎症反应、自噬和Nrf2信号通路的可能机制

4 结语和展望

4.1 畜禽养殖生产过程中释放的大量颗粒物严重影响环境空气质量和家畜健康,而颗粒物对环境和家畜健康的危害程度与其组成和浓度密切相关,因而确切掌握颗粒物的组成和形态以及排放规律对减少和控制颗粒物的排放非常重要。然而,目前畜禽舍颗粒物初级来源和次级来源难以区分,排放量计算存在差异,分析方法不统一,这些还有待进一步提高改进。

4.2 已有大量关于鸡舍和猪舍中颗粒物排放特点的研究。家畜舍类型、饲养方式、家畜类型、环境因子等均为影响颗粒物水平的重要因素。目前缺少标准化设备和方法来测量不同类型的畜禽舍颗粒物的浓度和排放水平。

4.3 畜禽舍中颗粒物吸附的刺激性气体、恶臭化合物以及致病性和非致病性的微生物的种类需要进一步明确。

4.4 大量试验研究了畜禽舍颗粒物对呼吸道的危害,但基于实验条件限制,多为采集畜禽舍颗粒物在实验室进行体外细胞试验或以小鼠为模型的在体试验,而缺少以畜禽为模型的在体试验研究。

4.5 目前关于颗粒物对机体的损伤机制研究主要集中在颗粒物对呼吸道的致炎作用。但颗粒物成分复杂,并处在不断变化中,因此颗粒物诱导机体损伤的机制也十分复杂,仍需进一步探究颗粒物对机体的损伤机理并总结出不同来源颗粒物对不同细胞损伤的共通性,以找出颗粒物引起细胞损伤的治疗靶点和适合的缓解物质。

[1] AL HOMIDAN A, ROBERTSON J. Effect of litter type and stocking density on ammonia, dust concentrations and broiler performance., 2003, 44: 7-8.

[2] ANDERSEN C, VON ESSEN S G, SMITH L, SPENCER J, JOLIE R, DONHAM K J. Respiratory symptoms and airway obstruction in swine veterinarians: A persistent problem., 2004, 46(4): 386-392.

[3] SABINO R, FAíSCA V M, CAROLINO E, VERISSIMO C, VIEGAS C. Occupational exposure to aspergillus by swine and poultry farm workers in portugal., 2012, 75(22-23): 1381-1391.

[4] GRIMM E. Control of pm emission from livestock farming installations in germany., 2007: 21-26.

[5] KLIMONT Z, WAGNER F, AMANN M, COFALA J, SCHöPP W, HEYES C, BERTOK I, ASMAN W. The role of agriculture in the european commission strategy to reduce air pollution., 2007, 308: 3-10.

[6] CHARDON W, VAN DER HOEK K. Berekeningsmethode voor de emissie vanfijn stof vanuit de landbouw. (Calculation method for emission of fine dust from agriculture). Alterra/RIVM, Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2002: 35.

[7] EMEP/CORINAIR Atmospheric Emission Inventory Guidebook. December 2007 Update, third ed. EEA, Copenhagen, Denmark.

[8] CAMBRALóPEZ M, AARNINK A J, ZHAO Y, CALVET S, TORRES A G. Airborne particulate matter from livestock production systems: A review of an air pollution problem., 2010, 158(1): 1-17.

[9] HETLAND R B, CASSEE F R, LåG M, REFSNES M, DYBING E, SCHWARZE P E. Cytokine release from alveolar macrophages exposed to ambient particulate matter: Heterogeneity in relation to size, city and season., 2005, 2(1): 1-15.

[10] 沈丹, 戴鹏远, 吴胜, 唐倩, 李春梅. 冬季封闭式肉种鸡舍空气颗粒物, 氨气和二氧化碳分布特点及 PM 2.5 理化特性分析. 畜牧兽医学报, 49(6): 1178-1193.

SHEN D, DAI P Y, WU S, TANG Q, LI C M. Distribution of particles, ammonia and carbon dioxide as well as physicochemical property of pm2.5in an enclosed broiler breeder house in winter., 49(6): 1178-1193.(in Chinese)

[11] ZHANG Y.. CRC Press, 2004.

[12] KULKARNI P, BARON P A, WILLEKE K. Aerosol fundamentals. In: Baron, P.A., Willeke, K.(Eds.),(seconded). Wiley, New York, 2001: 45–57.

[13] 刘志荣. 谈谈大气颗粒物的分类和命名.中国科技术语, 2013(2): 31-34.

LIU Z R. Discuss the classification and naming of atmospheric particulates., 2013 (2): 31-34. (in Chinese)

[14] DONHAM K J, SCALLON L J, POPENDORF W, TREUHAFT M W, ROBERTS R C. Characterization of dusts collected from swine confinement buildings., 47(7): 404-410.

[15] CAMBRA-LóPEZ M, TORRES A, AARNINK A, OGINK N. Source analysis of fine and coarse particulate matter from livestock houses., 2011, 45(3): 694-707.

[16] CURTIS S E, DRUMMOND J G, GRUNLOH D J, LYNCH P B, JENSEN A H. Relative and qualitative aspects of aerial bacteria and dust in swine houses., 1975, 41(5): 1512-1520.

[17] HONEY L, MCQUITTY J. Some physical factors affecting dust concentrations in a pig facility., 1979, 21(1): 9-14.

[18] AMADOR I R, PINTO J P, SOLCI M C. Concentration and size distribution of particulate matter in a broiler house ambient air., 2016, 8(3): 189-193.

[19] QI R, MANBECK H, MAGHIRANG R. Dust net generation rate in a poultry layer house., 1992, 35(5): 1639-1645.

[20] AARNINK A, STOCKHOFE-ZURWIEDEN N, WAGEMANS M. Dust in different housing systems for growing-finishing pigs., 2004.

[21] XUELAN L, ZHANG Y, PEIPEI Y, QINGCHUAN J, XIANGFA W, RUITING L, TIANHONG S, BIN W. Effects of different padding on air quality in broiler house and growth physiological index of broilers., 2015, 16(12):2764-2769.

[22] SEEDORF J, HARTUNG J. Emission of airborne particulates from animal production., 2000.

[23] CHAI L, ZHAO Y, XIN H, WANG T, ATILGAN A, SOUPIR M, LIU K. Reduction of particulate matter and ammonia by spraying acidic electrolyzed water onto litter of aviary hen houses–a lab-scale study.:, 2016.

[24] SHEPHERD T A, ZHAO Y, LI H, STINN J P, HAYES M D, XIN H. Environmental assessment of three egg production systems—part ii. Ammonia, greenhouse gas, and particulate matter emissions., 2015, 94(3): 534-543.

[25] SHEN D, WU S, DAI P Y, TANG Q, LI C M. Distribution of particulate matter and ammonia and physicochemical properties of fine particulate matter in a layer house., in press.

[26] HARTUNG J, SALEH M. Composition of dust and effects on animals.2007,308: 111-116.

[27] SCHNEIDER T, SCHLüNSSEN V, VINZENTS P, KILDESø J. Passive sampler used for simultaneous measurement of breathing zone size distribution, inhalable dust concentration and other size fractions involving large particles., 2002, 46(2): 187-195.

[28] XU W, ZHENG K, MENG L, LIU X, HARTUNG E, ROELCKE M, ZHANG F. Concentrations and emissions of particulate matter from intensive pig production at a large farm in north china., 2016, 16(1): 79-90.

[29] CAMBRA-LóPEZ M, TORRES A, AARNINK A, OGINK N. Source analysis of fine and coarse particulate matter from livestock houses., 2011, 45: 694-707.

[30] ELLEN H, BOTTCHER R, VON WACHENFELT E, TAKAI H. Dust levels and control methods in poultry houses., 2000, 6(4): 275-282.

[31] HAEUSSERMANN A, COSTA A, AERTS J-M, HARTUNG E, JUNGBLUTH T, GUARINO M, BERCKMANS D. Development of a dynamic model to predict pm emissions from swine houses., 2008, 37(2): 557-564.

[32] 吴胜, 沈丹, 唐倩, 戴鹏远,李延森,李春梅. 规模化半封闭式猪场舍内颗粒物、氨气和二氧化碳分布规律. 畜牧与兽医, 2018(3): 30-38.

WU S, SHEN D, TANG Q, DAI P Y, LI Y S, LI C M. Distribution of particulate matters and noxious gases in large-scale and semi-enclosed swine houses., 2018, 50(3): 30-38. (in Chinese)

[33] BANHAZI T, SEEDORF J, LAFFRIQUE M, RUTLEY D. Identification of the risk factors for high airborne particle concentrations in broiler buildings using statistical modelling., 2008, 101(1): 100-110.

[34] PUMA M, MAGHIRANG R, HOSNI M, HAGEN L. Modeling of dust concentration distribution in a simulated swine room under non-isothermal conditions., 1999, 42(6): 1823-1832.

[35] PUMA M, MAGHIRANG R, HOSNI M, HAGEN L. Modeling dust concentration distribution in a swine house under isothermal conditions., 1999, 42(6): 1811-1822.

[36] WOOD D J, VAN HEYST B J. A review of ammonia and particulate matter control strategies for poultry housing., 2016, 59(1): 329-344.

[37] CAMBRA-LóPEZ M, AARNINK A J, ZHAO Y, CALVET S, TORRES A G. Airborne particulate matter from livestock production systems: A review of an air pollution problem., 2010, 158(1): 1-17.

[38] HINZ T, LINKE S, KARLOWSKI J, MYCZKO R, KUCZYNSKI T, BERK J. PM emissions in and from force-ventilated turkey and dairy cattle houses as factor of health and the environment., 2007: 306-405.

[39] HINZ T, LINKE S, BITTNER P, KARLOWSKI J, KOLODZIEJCZYK T. Measuring particle emissions in and from a polish cattle house., 2007.

[40] HINZ T, LINKE S. A comprehensive experimental study of aerial pollutants in and emissions from livestock buildings. Part 2: Results., 1998, 70(1): 119-129.

[41] YODER M, VAN WICKLEN G. Respirable aerosol generation by broiler chickens., 1988, 31(5): 1510-1517.

[42] TAKAI H, PEDERSEN S, JOHNSEN J O, METZ J, KOERKAMP P G, UENK G, PHILLIPS V, HOLDEN M, SNEATH R, SHORT J. Concentrations and emissions of airborne dust in livestock buildings in northern europe., 1998, 70(1): 59-77.

[43] WATHES C, HOLDEN M, SNEATH R, WHITE R, PHILLIPS V. Concentrations and emission rates of aerial ammonia, nitrous oxide, methane, carbon dioxide, dust and endotoxin in uk broiler and layer houses., 1997, 38(1): 14-28.

[44] REDWINE J S, LACEY R E, MUKHTAR S, CAREY J. Concentration and emissions of ammonia and particulate matter in tunnel–ventilated broiler houses under summer conditions in texas., 2002, 45(4): 1101-1109.

[45] Al HOMIDAN A, ROBERTSON J F, PETCHEY A M. Effect of environmental factors on ammonia and dust production and broiler performance., 1998, 39: S9-S10.

[46] ELLEN H H, DOLEGHS B, ZOONS J. Influence of air humidity on dust concentration in broiler houses., 1999, Aarhus, Denmark.

[47] VUCEMILO M, MATKOVIC K, VINKOVIC B, MACAN J, VARNAI V M, PRESTER L J, GRANIC K, ORCT T. Effect of microclimate on the airborne dust and endotoxin concentration in a broiler house., 2008, 53 (2): 83-89.

[48] GUSTAFSSON G, VON WACHENFELT E. Airborne dust control measures for floor housing system for laying hens., 2006, VII: 1-13.

[49] HEBER A J, STROIK M, NELSSEN J L, NICHOLS D A. Influence of environmental factors on concentrations and inorganic content of aerial dust in swine finishing buildings., 1998(b), 31 (3): 875-881.

[50] MAGHIRANG R G, PUMA M C, LIU Y, CLARK P. Dust concentrations and particle size distribution in an enclosed swine nursery., 1997, 40 (3): 749-754.

[51] GUSTAFSSON G. Factors affecting the release and concentration of dust in pig houses., 1999, 74 (4): 379-390.

[52] HAEUSSERMANN A, FISHER D, JUNGBLUTH T, BAUR J, HARTUNG E. Aerosol indoor concentration and particulate emission in fattening pig husbandry., 2006, AgEng Bonn, Germany, 2006.

[53] VIEGAS S, FAíSCA V M, DIAS H, CLéRIGO A, CAROLINO E, VIEGAS C. Occupational exposure to poultry dust and effects on the respiratory system in workers., 2013, 76(4-5): 230-239.

[54] FRANZI L M, LINDERHOLM A L, RABOWSKY M, LAST J A. Lung toxicity in mice of airborne particulate matter from a modern layer hen facility containing proposition 2-compliant animal caging., 2016,33(3):211-221.

[55] HARRY E. Air pollution in farm buildings and methods of control: A review., 1978, 7(4): 441-454.

[56] HOUSE J S, WYSS A B, HOPPIN J A, UMBACH D M, LONDON S. Early-life farming exposures and adult atopy: The agricultural lung health study.:, 2016: A6695.

[57] RAASCHOU-NIELSEN O, BEELEN R, WANG M, HOEK G, ANDERSEN Z, HOFFMANN B, STAFOGGIA M, SAMOLI E, WEINMAYR G, DIMAKOPOULOU K. Particulate matter air pollution components and risk for lung cancer., 2016, 87: 66-73.

[58] SKóRA J, MATUSIAK K, WOJEWóDZKI P, NOWAK A, SULYOK M, LIGOCKA A, OKRASA M, HERMANN J, GUTAROWSKA B. Evaluation of microbiological and chemical contaminants in poultry farms., 2016, 13(2): 1-16.

[59] LI Q-F, WANG-LI L, LIU Z, JAYANTY R, SHAH S B, BLOOMFIELD P. Major ionic compositions of fine particulate matter in an animal feeding operation facility and its vicinity., 2014, 64(11): 1279-1287.

[60] MOSTAFA E, NANNEN C, HENSELER J, DIEKMANN B, GATES R, BUESCHER W. Physical properties of particulate matter from animal houses—empirical studies to improve emission modelling., 2016, 23(12): 12253-12263.

[61] ZHAO Y, AARNINK A J, DE JONG M C, GROOT KOERKAMP P W. Airborne microorganisms from livestock production systems and their relation to dust., 2014, 44(10): 1071-1128.

[62] NI L, CHUANG C C, ZUO L. Fine particulate matter in acute exacerbation of copd., 2015, 6: 1-10.

[63] SEEDORF J, HARTUNG J, SCHRöDER M, LINKERT K, PHILLIPS V, HOLDEN M, SNEATH R, SHORT J, WHITE R, PEDERSEN S. Concentrations and emissions of airborne endotoxins and microorganisms in livestock buildings in northern europe., 1998, 70(1): 97-109.

[64] SCHULZE A, VAN STRIEN R, EHRENSTEIN V, SCHIERL R, KUCHENHOFF H, RADON K. Ambient endotoxin level in an area with intensive livestock production., 2006, 13(1): 87-91.

[65] ZUCKER B A, MüLLER W. Concentrations of airborne endotoxin in cow and calf stables., 1998, 29(1): 217-221.

[66] SPAAN S, WOUTE RS I M, OOSTING I, DOEKES G, HEEDERIK D. Exposure to inhalable dust and endotoxins in agricultural industries., 2006, 8(1): 63-72.

[67] SCHUIJS M J, WILLART M A, VERGOTE K, GRAS D, DESWARTE K, EGE M J, MADEIRA F B, BEYAERT R, VAN LOO G, BRACHER F. Farm dust and endotoxin protect against allergy through a20 induction in lung epithelial cells., 2015, 349(6252): 1106-1110.

[68] LONDON S, HOPPIN J A, WYSS A, HOUSE J S, HENNEBERGER P K, UMBACH D M, THORNE P S, CARNES M U. House dust endotoxin levels are associated with adult asthma in the agricultural lung health study.:2016: A2781.

[69] MULLER-SUUR C, LARSSON K, MALMBERG P, LARSSON P. Increased number of activated lymphocytes in human lung following swine dust inhalation., 1997, 10(2): 376-380.

[70] SCHORLEMMER H, EDWARDS J, DAVIES P, ALLISON A. Macrophage responses to mouldy hay dust, micropolyspora faeni and zymosan, activators of complement by the alternative pathway., 1977, 27(2): 198-207.

[71] BAUER C, KIELIAN T, WYATT T A, ROMBERGER D J, WEST W W, GLEASON A M, POOLE J A. Myeloid differentiation factor 88-dependent signaling is critical for acute organic dust-induced airway inflammation in mice., 2013, 48(6): 781-789.

[72] DUSAD A, THIELE G M, KLASSEN L W, WANG D, DURYEE M J, MIKULS T R, STAAB E B, WYATT T A, WEST W W, REYNOLDS S J. Vitamin d supplementation protects against bone loss following inhalant organic dust and lipopolysaccharide exposures in mice., 2015, 62(1): 46-59.

[73] GOLDEN G A, WYATT T A, ROMBERGER D J, REIFF D, MCCASKILL M, BAUER C, GLEASON A M, POOLE J A. Vitamin d treatment modulates organic dust-induced cellular and airway inflammatory consequences., 2013, 27(1): 77-86.

[74] POOLE J A, WYATT T A, OLDENBURG P J, ELLIOTT M K, WEST W W, SISSON J H, VON ESSEN S G, ROMBERGER D J. Intranasal organic dust exposure-induced airway adaptation response marked by persistent lung inflammation and pathology in mice., 2009, 296(6): 1085-1095.

[75] POOLE J A, THIELE G M, ALEXIS N E, BURRELL A M, PARKS C, ROMBERGER D J. Organic dust exposure alters monocyte-derived dendritic cell differentiation and maturation., 2009, 297(4): 767-776.

[76] EASTMAN C, SCHENKER M B, MITCHELL D C, TANCREDI D J, BENNETT D H, MITLOEHNER F M. Acute pulmonary function change associated with work on large dairies in california., 2013, 55(1): 74-79.

[77] FENG S, GAO D, LIAO F, ZHOU F, WANG X. The health effects of ambient PM2.5and potential mechanisms., 2016, 128: 67-74.

[78] DENG X, WEI R, FANG Z, DING W. PM2.5induces Nrf2-mediated defense mechanisms against oxidative stress by activating PI3K/AKT signaling pathway in human lung alveolar epithelial A549 cells., 2013, 29(3): 143-157.

[79] LIMóN-PACHECO J, GONSEBATT M E. The role of antioxidants and antioxidant-related enzymes in protective responses to environmentally induced oxidative stress., 2009, 674(1): 137-147.

[80] HARRIS G K, SHI X. Signaling by carcinogenic metals and metal- induced reactive oxygen species., 2003, 533(1): 183-200.

[81] HUANG J, LAM G Y, BRUMELL J H. Autophagy signaling through reactive oxygen species., 2011, 14(11): 2215-2231.

[82] NAIK E, DIXIT V M. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species drive proinflammatory cytokine production., 2011, 208(3): 417-420.

[83] DAVIS R J. Signal transduction by the JNK group of map kinases., 2000, 103(2): 239-252.

[84] MIYATA R, VAN EEDEN S F. The innate and adaptive immune response induced by alveolar macrophages exposed to ambient particulate matter., 2011, 257(2): 209-226.

[85] MARANO F, BOLAND S, BONVALLOT V, BAULIG A, BAEZA-SQUIBAN A. Human airway epithelial cells in culture for studying the molecular mechanisms of the inflammatory response triggered by diesel exhaust particles., 2002, 18(5): 315-320.

[86] GUNTER T E, GUNTER K K, SHEU S-S, GAVIN C E. Mitochondrial calcium transport: Physiological and pathological relevance., 1994, 267(2): 313-339.

[87] CHAN S-L, LINDQUIST L D, HANSEN M J, GIRTMAN M A, PEASE L R, BRAM R J. Calcium-modulating cyclophilin ligand is essential for the survival of activated t cells and for adaptive immunity., 2015, 195(12): 5648-5656.

[88] XING Y F, XU Y H, SHI M H, LIAN Y X. The impact of PM2.5on the human respiratory system., 2016, 8(1): 69-74.

[89] HE M, ICHINOSE T, YOSHIDA Y, ARASHIDANI K, YOSHIDA S, TAKANO H, SUN G, SHIBAMOTO T. Urban PM2.5exacerbates allergic inflammation in the murine lung via a TLR2/TLR4/ Myd88-signaling pathway., 2017, 7(1): 1-9.

[90] HE M, ICHINOSE T, REN Y, SONG Y, YOSHIDA Y, ARASHIDANI K, YOSHIDA S, NISHIKAWA M, TAKANO H, SUN G. Pm2.5-rich dust collected from the air in fukuoka, kyushu, japan, can exacerbate murine lung eosinophilia., 2015, 27(6): 287-299.

[91] MAHLA R S, REDDY C M, PRASAD D, KUMAR H. Sweeten pamps: Role of sugar complexed pamps in innate immunity and vaccine biology., 2013, 4: 1-16.

[92] JIMéNEZ-DALMARONI M J, GERSWHIN M E, ADAMOPOULOS I E. The critical role of toll-like receptors—from microbial recognition to autoimmunity: A comprehensive review., 2016, 15(1): 1-8.

[93] BECKER S, DAILEY L, SOUKUP J M, SILBAJORIS R, DEVLIN R B. Tlr-2 is involved in airway epithelial cell response to air pollution particles., 2005, 203(1): 45-52.

[94] FUERTES E, BRAUER M, MACINTYRE E, BAUER M, BELLANDER T, VON BERG A, BERDEL D, BRUNEKREEF B, CHAN-YEUNG M, GEHRING U. Childhood allergic rhinitis, traffic-related air pollution, and variability in the GSTP1 , TNF , TLR2 , and TLR4 genes: results from the TAG study., 2013, 132(2): 342-352.

[95] ZHAO C, LIAO J, CHU W, WANG S, YANG T, TAO Y, WANG G. Involvement of TLR2 and TLR4 and Th1/Th2 shift in inflammatory responses induced by fine ambient particulate matter in mice., 2012, 24(13): 918-927.

[96] SHOENFELT J, MITKUS R J, ZEISLER R, SPATZ R O, POWELL J, FENTON M J, SQUIBB K A, MEDVEDEV A E. Involvement of tlr2 and tlr4 in inflammatory immune responses induced by fine and coarse ambient air particulate matter., 2009, 86(2): 303-312.

[97] DEGUINE J, BARTON G M. Myd88: A central player in innate immune signaling., 2014, 6(97): 1-7.

[98] POOLE J A, WYATT T A, KIELIAN T, OLDENBURG P, GLEASON A M, BAUER A, GOLDEN G, WEST W W, SISSON J H, ROMBERGER D J. Toll-like receptor 2 regulates organic dust- induced airway inflammation., 2011, 45(4): 711-719.

[99] ZENG Y, YANG X, WANG J, FAN J, KONG Q, YU X. Aristolochic acid I induced autophagy extenuates cell apoptosis via ERK1/2 pathway in renal tubular epithelial cells., 2012, 7(1): 1-10.

[100] POON A H, CHOUIALI F, TSE S M, LITONJUA A A, HUSSAIN S N, BAGLOLE C J, EIDELMAN D H, OLIVENSTEIN R, MARTIN J G, WEISS S T. Genetic and histological evidence for autophagy in asthma pathogenesis., 2012, 129(2): 1-7.

[101] DENG X, ZHANG F, WANG L, RUI W, LONG F, ZHAO Y, CHEN D, DING W. Airborne fine particulate matter induces multiple cell death pathways in human lung epithelial cells., 2014, 19(7): 1099-1112.

[102] LIU T, WU B, WANG Y, HE H, LIN Z, TAN J, YANG L, KAMP D W, ZHOU X, TANG J. Particulate matter 2.5 induces autophagy via inhibition of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/akt/mammalian target of rapamycin kinase signaling pathway in human bronchial epithelial cells., 2015, 12(2): 1914-1922.

[103] SU R, JIN X, ZHANG W, LI Z, LIU X, REN J. Particulate matter exposure induces the autophagy of macrophages via oxidative stress-mediated PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway., 2017, 167: 444-453.

[104] WANG Y, LIN Z, HUANG H, HE H, YANG L, CHEN T, YANG T, REN N, JIANG Y, XU W. AMPK is required for PM2.5-induced autophagy in human lung epithelial A549 cells., 2015, 8(1): 1-15.

[105] JONES S A, MILLS K H, HARRIS J. Autophagy and inflammatory diseases., 2013, 91(3): 250-258.

[106] TAL M C, SASAI M, LEE H K, YORDY B, SHADEL G S, IWASAKI A. Absence of autophagy results in reactive oxygen species-dependent amplification of rlr signaling., 2009, 106(8): 2770-2775.

[107] FAN X, WANG J, HOU J, LIN C, BENSOUSSAN A, CHANG D, LIU J, WANG B. Berberine alleviates ox-LDL induced inflammatory factors by up-regulation of autophagy via AMPK/mTOR signaling pathway., 2015, 13(1): 92-103.

[108] DENG X, RUI W, ZHANG F, DING W. PM2.5induces Nrf2-mediated defense mechanisms against oxidative stress by activating PI3K/AKT signaling pathway in human lung alveolar epithelial A549 cells., 2013, 29(3): 143-157.

[109] 何贤辉, 何健, 欧阳东云. 细胞自噬与炎症反应相互作用的研究进展.暨南大学学报: 自然科学与医学版, 2013, 34(2): 125-128.

HE X H, HE J, OUYANG D Y. Research progress in the interaction between autophagy and inflammatory response.:, 2013, 34(2): 125-128. (in Chinese)

(责任编辑 林鉴非)

Research Progress on Characteristics of Particulate Matter in Livestock Houses and Its Harmful Effects on Respiratory Tract Health of Livestock and Poultry

DAI PengYuan, SHEN Dan, TANG Qian, LI YanSen, LI ChunMei

(College of Animal Science & Technology Nanjing Agricultural University,Nanjing 210095)

With the improvement of livestock and poultry intensive breeding, high density breeding livestock and poultry farms air quality problem becomes increasingly prominent. The livestock production process can generate a large number of PM, which has become an important source of fine particulate PM2.5(aerodynamic diameter ≤ 2.5 μm) and PM10(aerodynamic diameter ≤ 10 μm ) in atmosphere, affecting the air quality and the health of livestock seriously. PM in livestock houses is mainly organic and mainly from feed, feces, feathers, dander, containing C, H, O, N, S, Ca, Na, Mg, Al, K, and other elements; the surface of PM also adheres to bacteria, fungi, viruses, endotoxins, ammonia gas, hydrogen sulfide and other harmful substances. It was found that PM concentration in chicken house was higher than that in pig house; PM concentration in livestock houses was positively correlated with the age and activity of animals; PM concentration in winter was higher than that in summer. However, there is a lack of standardized equipment and standard methods to measure PM concentration and emission levels in different types of livestock and poultry houses. PM components in livestock houses are complex and have strong biological effects, which seriously hazard the health and animal production. High PM concentration in livestock houses affects respiratory health mainly in the following three forms: the directly stimulation of PM to respiratory tract which reduces the immune resistance of the body to respiratory diseases; the stimulation of various compounds attached to PM surface; the stimulation of pathogenic and non-pathogenic microorganisms on PM surfaces. At present, studies on the mechanism of PM on respiratory health hazards mainly focus on the inflammatory effect of PM on respiratory tract Studies showed that, PM could induce cells to release inflammatory factors and cause lung inflammation reaction through the proinflammatory factor produced by alveolar macrophages stimulated by PM. In addition, PM2.5upregulated the expression of nuclear transcription factor κB (NFκB) and transcription activator AP-1 by mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPKs) which was activated by oxidative stress. PM2.5could also identify the toll-like receptor 2 and 4 by activating the mode of activation, and activate the NFκB signaling pathway, leading to the occurrence of inflammation. Studies have also found that the cell autophagy and nuclear factor related factor - 2 (nuclear factor E2 - related factor 2, Nrf2) related signaling pathways would be activated during the process of inflammation induced by PM2.5, which provided the targets for treatment of cell damage induced by PM2.5. Although there were more study on mechanism of hazard of PM to the health of respiratory tract, the PM composition was complicated, and in a constantly changing, so the PM induced respiratory damage mechanism was very complex and need further study. A large number of PM released in the process of livestock production seriously affects the environmental air quality and the health of livestock, and the extent of PM's harm to the environment and the health of livestock was closely related to its composition and concentration. Therefore, a proper understanding of PM morphology, size, composition, concentration level and emission influencing factors of animal house is of great significance to the determination of PM source and hazard caused by PM toxicity. In this paper, the source, chemical composition, concentration, discharge, influence factors, and the effects on respiratory function of PM from animal house are summarized, and offer a base for evaluating the effect of PM on healthy production of livestock and poultry.

livestock house; particulate matter; pollution characteristics; respiratory tract damage

2018-04-11;

2018-07-17

“十三五”国家重点研发计划(2016YFD0500505);国家自然科学基金(31772648)

戴鹏远,Tel:025-84395971;E-mail:2015205015@njau.edu.cn。

李春梅,Tel:025-84395971;E-mail:chunmeili@njau.edu.cn

10.3864/j.issn.0578-1752.2018.16.017